On wine and hashish • Charles Baudelaire

The Manesse Verlag has long held a special place in my heart, primarily because of its Library of World Literature. In addition to this vast and inexhaustible source of excellent books, there are always new releases that I simply cannot resist—usually beautifully designed volumes or newly discovered treasures from past centuries. Such is the case with Wine and Hashish by Charles Baudelaire, a title that kept crossing my path until I could no longer resist. Until now, I only knew the author in connection with Gustave Flaubert. A lovely little book, a promising author, and the Manesse Verlag: a good combination.

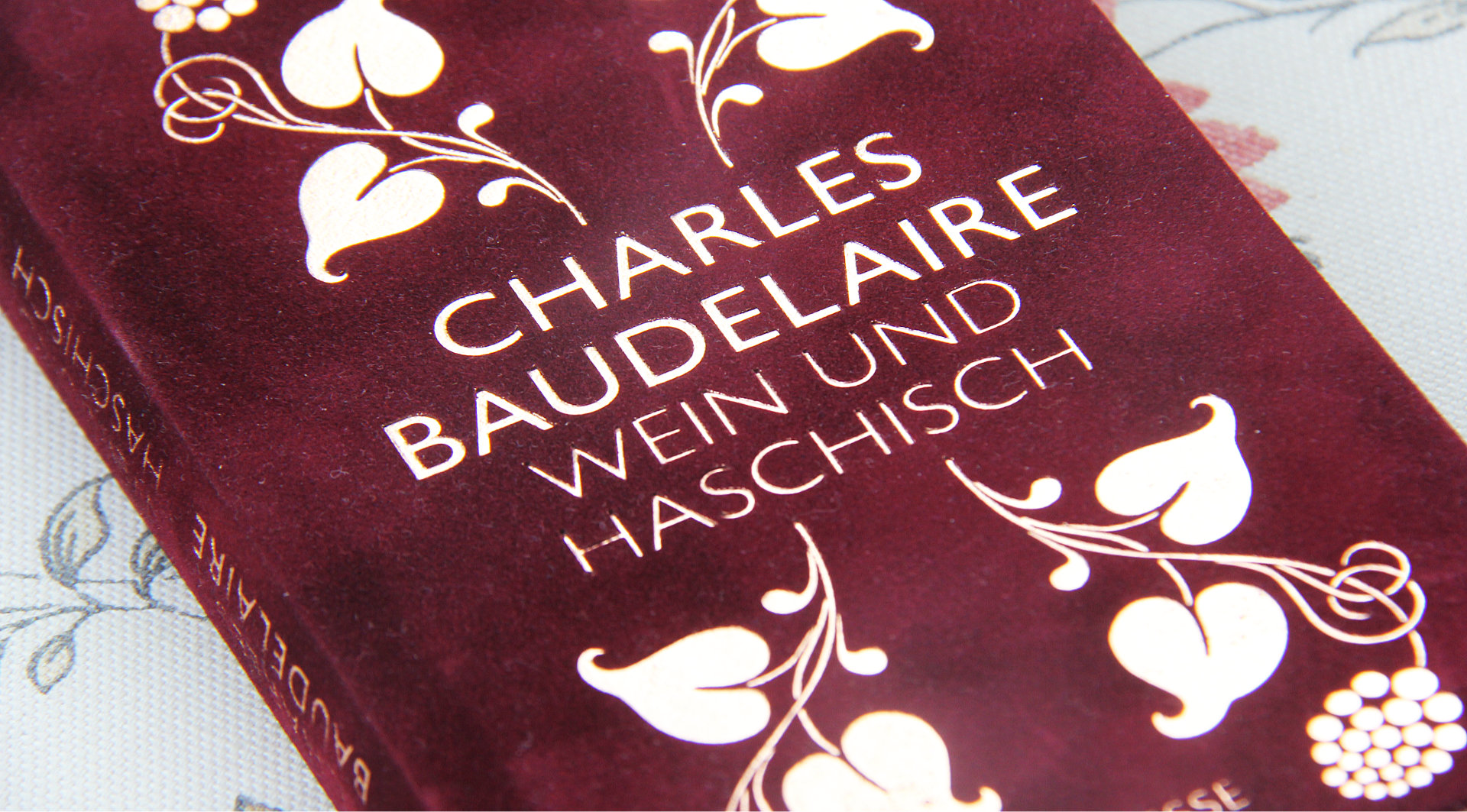

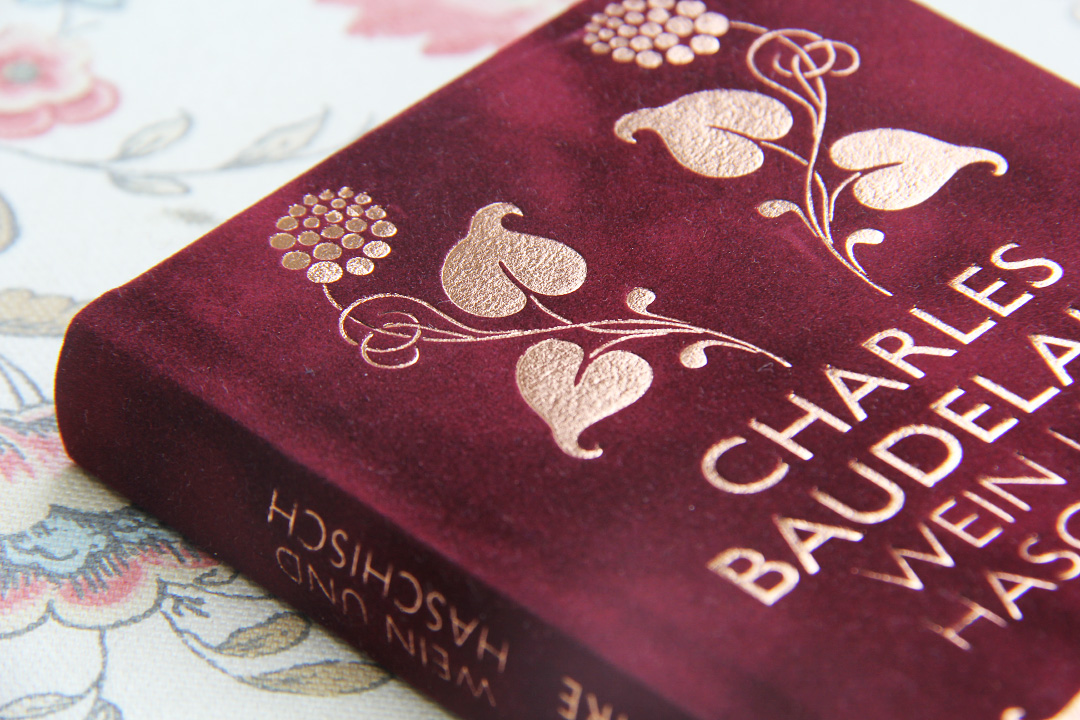

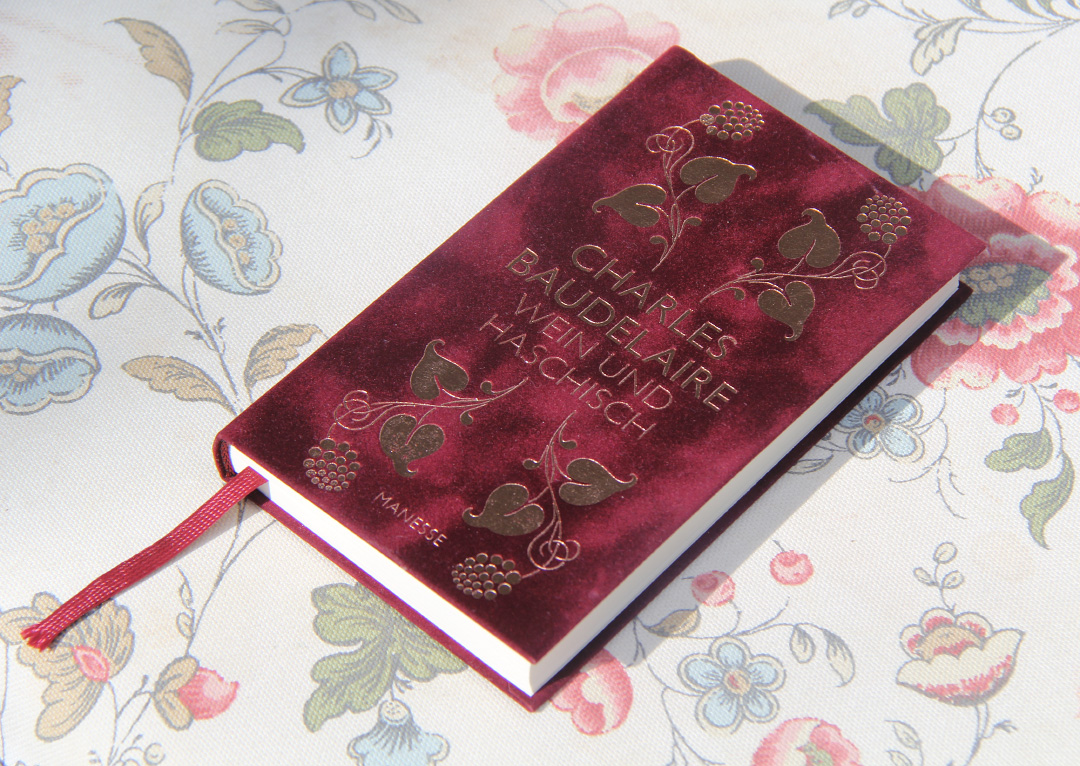

Charles Baudelaire was known primarily as a poet, and with his collection Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil), he was charged with “insulting public morality.” Quite similarly to his contemporary and friend Gustave Flaubert—only that Baudelaire was convicted, while Flaubert was acquitted. That was all I knew of Baudelaire, and since I don’t particularly care for poetry, I had never paid much attention to him. This book, however, piqued my curiosity nonetheless. Wine and Hashish—already a provocative title—but what convinced me even more was the entire concept: a small, bibliophile book bound in velvet with gold, ornate lettering, containing essays by an “ironic bon vivant and eloquent protagonist of the Parisian bohemia.” It all fits together perfectly.

The selection of essays is well-balanced, thoughtfully curated, and quite successful. Naturally, it is about wine and hashish, but also about love, music, Flaubert’s Emma, and about God and the world. In an easygoing tone, Baudelaire philosophizes on all sorts of topics, and reading it is genuinely entertaining and stimulating. I can only recommend enjoying a glass of wine—or in my case, a beer—while reading it, to experience a slight intoxication. Both from the wine and from the text, for Baudelaire’s words carry the same haze as those late-night conversations that unfold during a long dinner and drinks (though, of course, expressed far more eloquently).

“Indeed, hatred is a precious liqueur, a more costly poison than that of the Borgias—for it is brewed from our blood, our health, our sleep, and two-thirds of our love! One must be stingy with it!” (p. 24)

The book contains six essays and begins with the Selection of Consoling Maxims on Love. This chapter only moderately impressed me. Some of his reflections struck me as rather shallow, bordering on clichés—though still entertaining to read. Advice to Young Writers contains a few tips for aspiring poets, although according to the afterword, Baudelaire himself rarely followed his own advice. What stuck with me most was his recommendation that “prostitutes or foolish women” (cf. p. 32) make suitable companions for writers. An essay that is consistently provocative and, of course, not to be taken entirely seriously.

The most beautiful essay, however, is indeed Wine and Hashish, written as promised with eloquence and irony. He glorifies wine, describes the effects of hashish, muses on how intoxication brings forth genius, how wine makes the worker’s mundane life bearable, and finally concludes that perhaps hashish consumption isn’t so advisable after all—since “Great poets, philosophers, prophets […] by the power of their will, achieve a state in which they are both cause and effect, subject and object, magnetizer and sleepwalker.” (p. 73). One cannot take him entirely seriously here either, but from his descriptions it is clear that he was fond of intoxication—a fact the afterword also confirms.

“Were wine to disappear from human production, I believe a deficiency would be felt in the planet’s wellbeing and intellect; something would be missing—a far more terrible gap than any excesses or errors ever caused by wine could create.” (pp. 43f)

His friend Théophile Gautier founded, together with Moreau, the “Club des Hashischins,” which met once a month. According to the notes, Baudelaire’s descriptions of hashish’s effects are based on eyewitness accounts from these meetings. Apparently, Baudelaire was not averse to drug use and indulged not only in wine but also, at times, in opium. As I have no personal experience with the intoxicating effects of such substances, I cannot judge how close his descriptions are to reality. Yet the way he writes about intoxication gives it a cultivated air—a touch of an elegant boudoir in pleasant company—and presents it as something rather harmless. But given the unpredictability of such effects, I would personally prefer a freshly poured beer over any narcotic concoctions. And even Baudelaire seems to come to that realization in the end:

“Wine is useful; it is fruitful. Hashish is useless and dangerous.” (p. 72)

The essay What Toys Teach Us recounts one of his childhood memories and explores the effect and perception of toys. It remains quite relevant today, and I found myself laughing out loud at some passages, as they reminded me of moments from my own life. There are indeed things that never change—like the flourishing imagination of children.

One essay is dedicated to Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert. It is surprisingly brief; I had expected more content here. As expected, he defends his fellow sufferer, and some of his formulations really hit the mark.

“We shall unfold a nervous, pictorial, subtle, and precise style upon a banal canvas. We shall insert the most burning and fermenting emotions into the most trivial of adventures.” (p. 95)

Overall, he picks out certain aspects but doesn’t treat this masterpiece exhaustively. Entertaining, yes, but not much stuck with me afterward. Still, I could always read more about my dear Emma—when it comes to her, it never gets boring.

In the final essay, Baudelaire turns to Richard Wagner and the Tannhäuser in Paris. The great composer was just beginning to establish himself in France, and his operas were being hotly debated in Paris at the time. Some anti-imperial aristocrats disrupted performances at the Italian Opera, and the press took Wagner to task. Baudelaire identifies himself here as an outsider and had already recognized Wagner’s exceptional talent. In this essay, he beautifully and eloquently interprets the significance of Wagner’s works, wonderfully describes the Tannhäuser overture, summarizes the operas published so far, and proclaims a Wagner who merges music and drama to fill the gaps left by each art form alone.

“I have often heard it said that music cannot claim to reproduce anything with certainty, as painting and words can. In a sense, that is true—but it is not the whole truth. Music expresses everything in its own way, with the means at its disposal. Like painting and even the written word, music always leaves a gap to be filled by the listener’s imagination.” (p. 112)

I often found myself in these essays—especially when he writes about how he experienced Wagner’s music, the changing yet recurring motifs that wind through the entire opera and reappear again and again. His interpretation of this observation is truly worth reading.

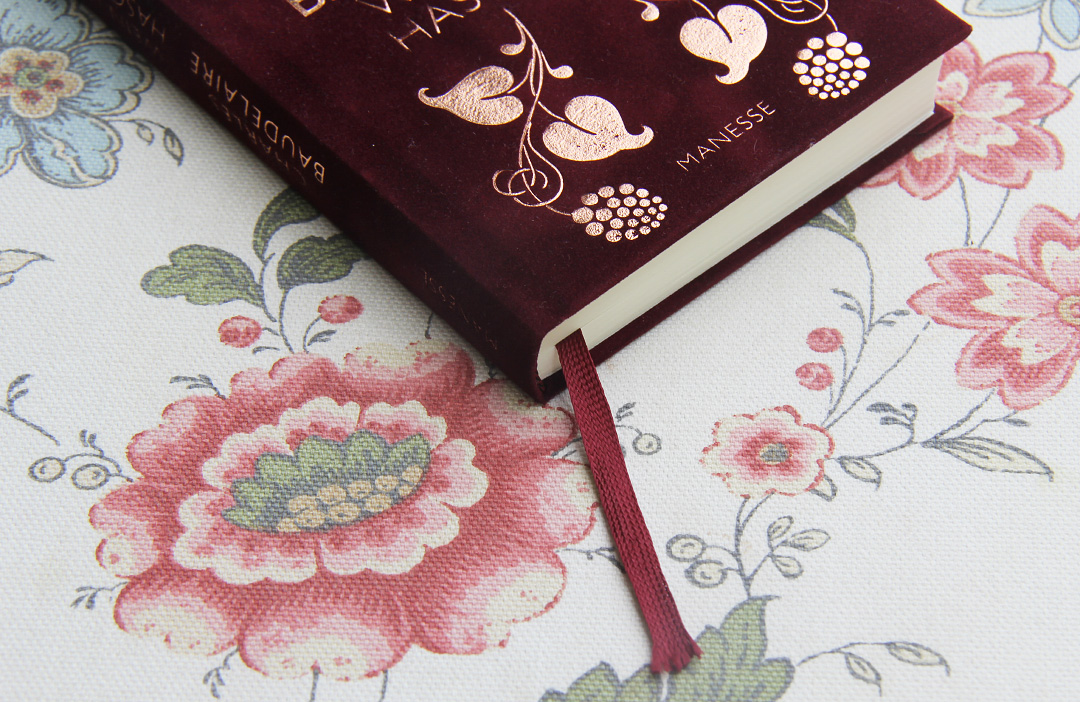

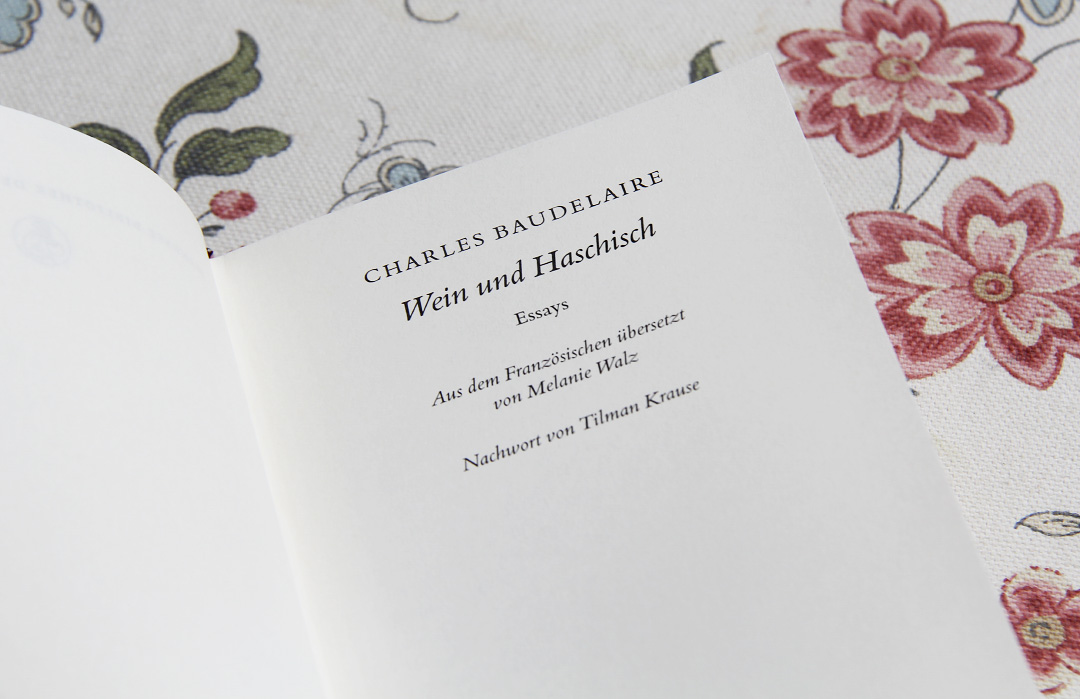

The essays were translated by Melanie Walz, which for me was another reason to pick up this book. The afterword by Tilman Krause is also well worth reading. The beautiful design deserves mention too: the cover is made of red velvet and decorated with golden embellishments. The book is quite small—just like the volumes in the Library of World Literature—but it looks truly elegant, atmospheric in every way, and visually captures the theme perfectly. It makes a wonderful gift book, and it has certainly earned a permanent spot on my shelf.

Conclusion: This small collection of essays is a lively and versatile read. I greatly enjoyed the wealth of thoughts, the philosophical musings, and the often ironic tone that shouldn’t always be taken too seriously. Especially the title essay, Wine and Hashish, stands out here. In the end, the book feels a bit like a cozy and animated conversation with a good friend. After an evening spent exchanging thoughts, discussing the world and beyond, slightly intoxicated by wine (or beer), recalling experiences and memories—when you finally part ways, there still lingers a haze of forgetfulness over all that philosophizing. A bibliophile and harmonious book that entertains well with its variety of themes and reflections, even if it doesn’t leave a deep mark.

Book information: On wine and Hashish • Charles Baudelaire • Manesse Verlag • 224 pages • ISBN 9783717524304

1 Comment