Lolita • Vladimir Nabokov

With Lolita, everyone can relate to it in some way, has heard the title of the book, or picked up the name somewhere else. But I would assume that only a few have actually read the book. The association is usually a precocious, seductive girl. Nabokov’s novel was a scandal, it polarized and continues to evoke numerous emotions these days. I would say the book is Kafka’s famous axe that breaks through the frozen sea within the reader and leaves no one untouched. I was surprised by its complexity and the nuanced portrayal it offers, and it quickly captivated me. It is by no means a frivolous or purely provocative story. The reader can expect truly great literature here. Read on to find out why you simply must read this book.

The main character Humbert narrates in this novel, from a first-person perspective, how he builds and acts out an obsessive and sexual relationship with the twelve-year-old Lolita. He directs this account to a fictional jury, with Humbert trying to justify his actions and present himself in a better light. The reader thus witnesses Humbert’s pedophilia, his emotions, his thoughts, how he approaches Lolita, how he abuses her, and what kind of life he ultimately leads with her.

After just a few chapters, it was clear to me that this book is a masterpiece. For numerous reasons. As a reader, you gain deep insight into Humbert’s thoughts. He describes how he feels drawn to children and differentiates here, designating certain girls who physically appeal to him as nymphs. These are girls between nine and fourteen years old, whom he finds particularly attractive and who, from his perspective, possess a perfect mixture of sensual stimulation and childish innocence. By chance, he meets Lolita, who seems to him like a perfect nymph. What strikes me as special about this is that it becomes comprehensible to the reader what is happening within Humbert. If one takes this thought process (even though it’s really difficult) and accepts this sexual obsession, then everything simply makes sense, then what Nabokov portrays here is coherent. Because Humbert wants to win the reader over to his side, he is not entirely unsympathetic to them. This fascinated me greatly, because it is not a crude or provocative portrayal of a conscienceless or emotionless pervert. Humbert is well-read, possesses beautiful and pleasant language, he is educated, he expresses his feelings in multifaceted ways, he is also aware of how reprehensible he is, and through this reflection, he appears human.

Who knows, perhaps the attraction that immaturity holds for me lies not so much in the evident charm of pure, young, forbidden fairy-child beauty as in the security of a situation in which boundless perfections fill the gap between the little that is given and the great that is promised—the great rosy-gray Never-to-be-attained.

Page 435f

What additionally fascinated me during the reading was a certain dissonance that repeatedly arose in my imagination. He describes the physical attributes of Lolita, for example, there is a well-executed passage where he describes her while playing tennis. My mind is simply unable to imagine a girl as sexually attractive. It just doesn’t work; it’s a loose end, there are simply no neurons in the brain for it, it runs completely into emptiness. However, the attributes he describes are indeed universal. For example, beautiful, luxuriant hair, attractive movements, youthful skin, and similar things. But through this, I always formed an image in my imagination of an attractive young woman and not a girl. But then there are passages where it becomes unmistakably clear to the reader that this is a child. And then in my imagination there was always that shift back, then this discrepancy became really palpably evident, and it was like a cold shower each time. A fascinating element that I have encountered in no other novel in quite this way.

What reinforces the effect of the novel is the language. These are beautiful sentences, it is simply well written, and the descriptions have a clear and powerful impact on the reader’s imagination. Although Nabokov describes no vulgar or explicit scenes. He always remains with allusions, with circumlocutions that make it unmistakably clear what is happening, but never depict the abuse in all its detail. For this, I was very grateful to Nabokov, because the reader is already extremely repulsed at numerous points just from this approach.

Nabokov enriched the novel with countless references and allusions. My edition contains numerous notes, and this occasionally made the reading somewhat tedious. It is impressive what Nabokov worked into the book, and you can simply sense his background as a literary scholar and his enthusiasm for James Joyce, who had done this in exaggerated form in his Ulysses. At the same time, this also makes the text somewhat less accessible. I find the references to Poe particularly successful, to Mérimée’s Carmen, or also elements where he worked his name in as an anagram, since he had assumed he would have to publish the book anonymously. However, I found the book somewhat overly extensive in places. When he describes travel routes and locations in detail, that doesn’t advance the story much. One could have condensed the entire text without significant losses there.

Another truly masterful element that distinguishes this novel is the unreliability of the narrator. Humbert wants to justify himself before the court and the jury, he wants to present himself in a good light, and he embellishes his account and tries to present himself as humanely as possible. Especially at the beginning, he succeeds quite well. But the further the novel progresses, the more clearly the reader becomes aware of how distorted this portrayal is. One example is an explanation he wants to give as the cause of his pedophilia. He refers to an experience from his adolescence in which a first love for a girl of the same age remained unfulfilled in a tragic way. He emphasizes her similarity to Lolita and wants to win the reader over in this way. Only much later does he refer to it again and relativizes this reference when he writes: “Enough of those special sensations which, influenced if not produced by the precepts of modern psychiatry.” (p. 275). This happens repeatedly throughout the novel, and the reader becomes increasingly aware that Humbert is not to be trusted.

Humbert’s passion lies like a cloth over the plot, and beneath it reality emerges ever more clearly as the story progresses. It is the small mentions that betray him and make clear how much Lolita suffers under this situation. In a way that only children can suffer—those who, because of their dependence, are at the mercy of a situation and cannot free themselves from it. The cruelty in that has shocked me repeatedly. The most beautiful language, all the means to somehow evoke sympathy, the glimpse into his refined thoughts, none of it takes hold, and as the story progresses, it becomes clear how ruthlessly he pursues his goals. Precisely this is what makes this novel so authentic and credible. These nuances, the numerous emotions that become evident, sometimes elaborately developed, sometimes only hinted at through a brief scene or statement, this entire complexity. One could read the novel multiple times and would continually discover new statements, thoughts, feelings, or references within it. The novel has a fascinating depth that can be found precisely in this.

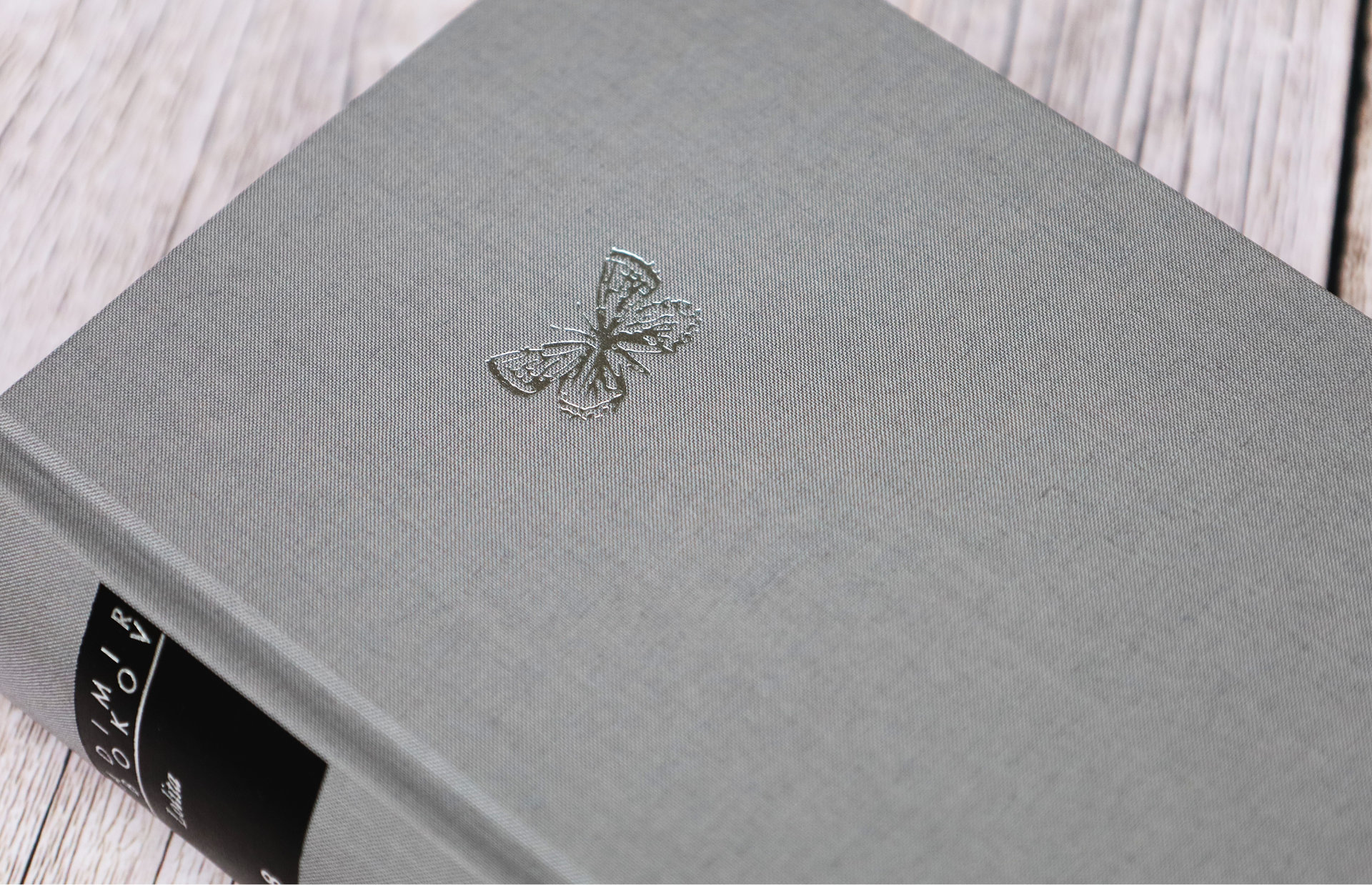

Vladimir Nabokov was born in 1899 in Saint Petersburg and had to flee Russia with his family in 1917. He himself experienced a beautiful and fulfilled childhood in a wealthy environment, which stands in stark contrast to his Lolita. His literary career began in Berlin, from which he had to flee again after the National Socialists came to power, this time with his Jewish wife, and he eventually emigrated to the United States. There, he taught at various universities. When Lolita appeared, he was already an experienced author and could look back on numerous publications. Lolita caused a scandal at the time, which among other things helped the book achieve commercial success and made Nabokov financially independent. The literary scholar and passionate butterfly researcher died in 1977 in Switzerland.

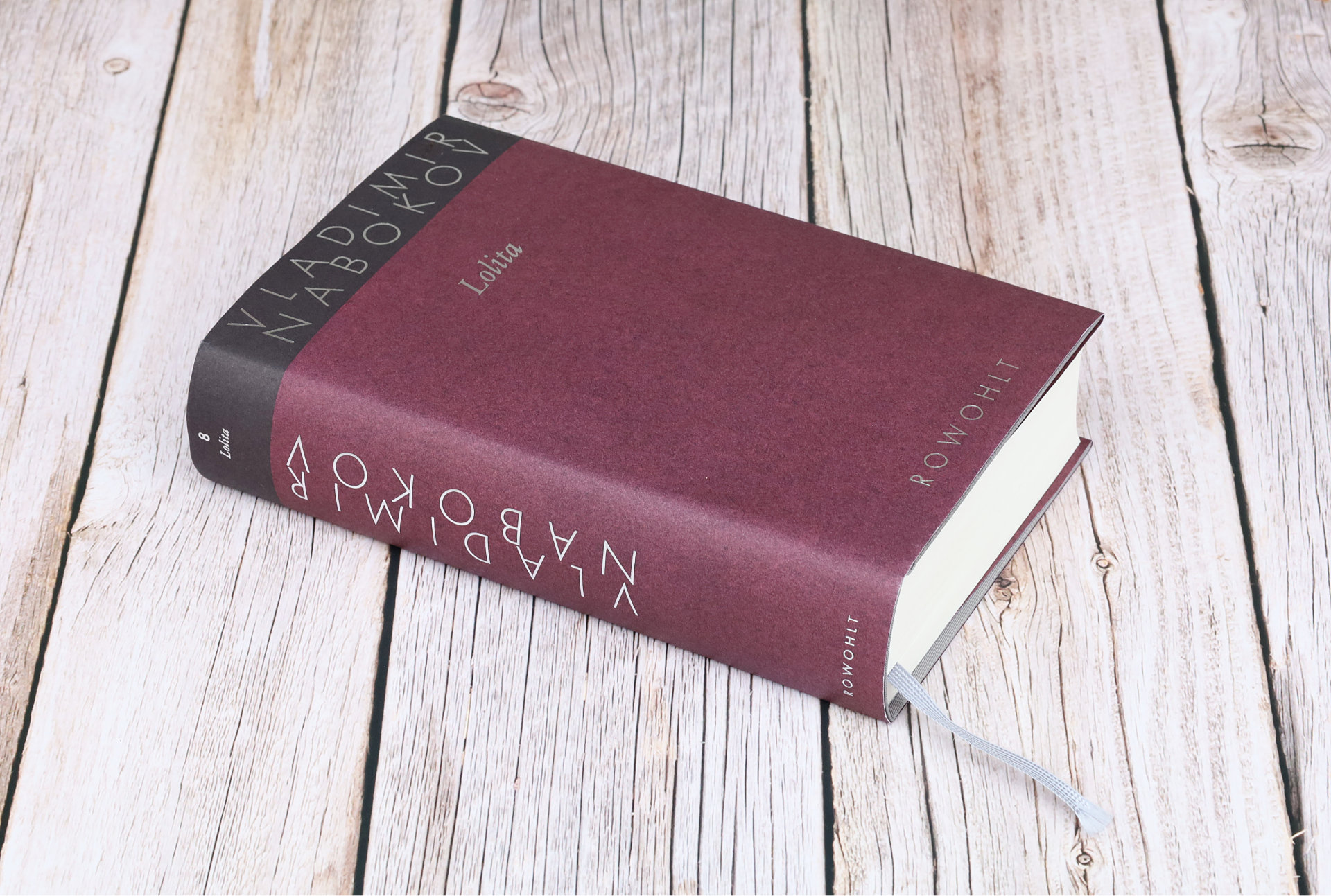

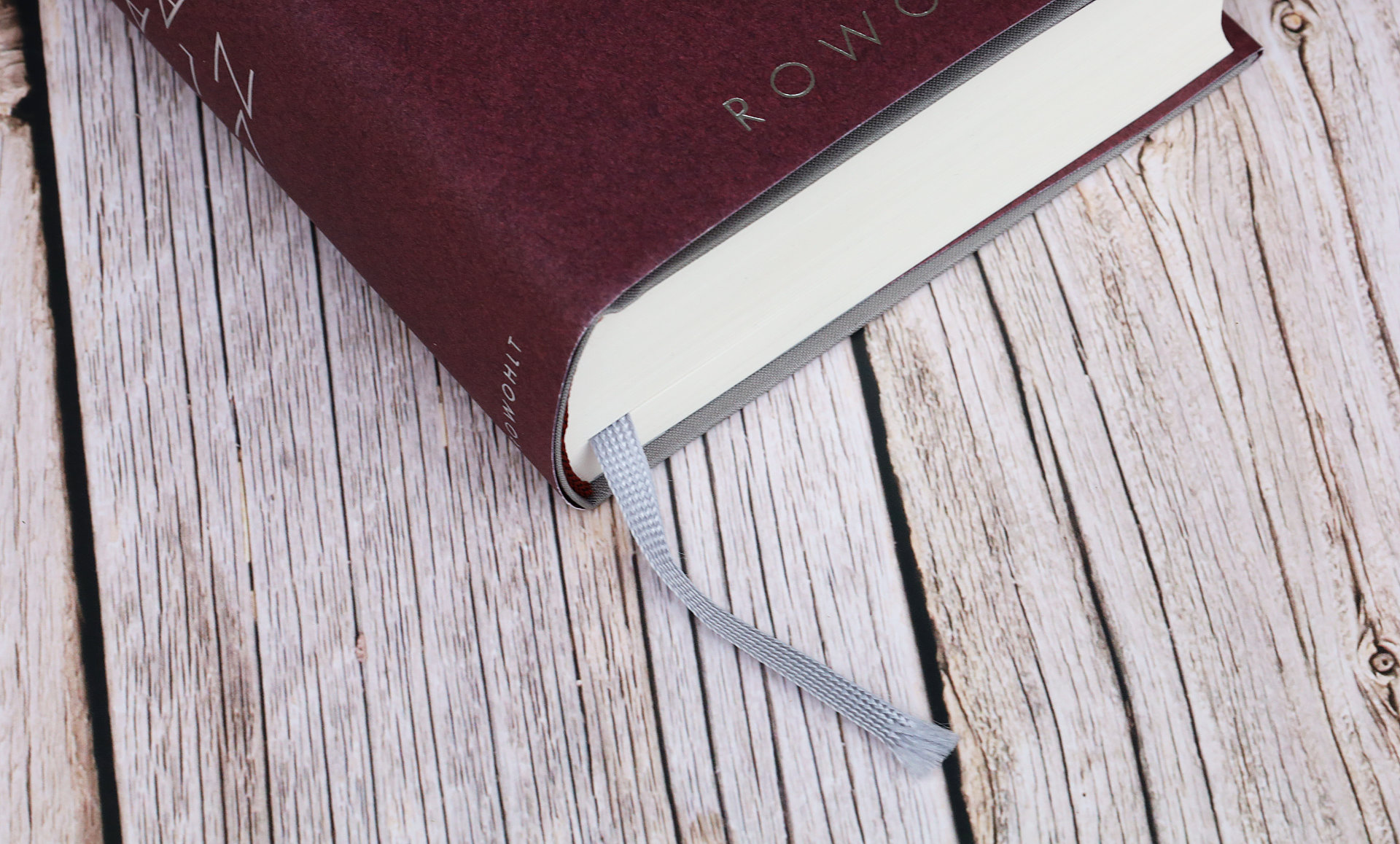

I chose the edition from Rowohlt Verlag, which is very expensive, but beautifully bound, equipped with sewn binding and a ribbon bookmark. The cover design is rather dull, but the book is excellently processed. The quality of the translation is outstanding, and the numerous notes provide important and good explanations. Nabokov originally wrote the book in English. In an interview, he mentions that he has great concerns that the book will be translated into his native Russian language in poor quality. So he decided to translate the novel himself, which he did in 1967. This edition contains Nabokov’s afterwords from the English and Russian editions, which were really very interesting to read. Furthermore, the notes contain the differences to the Russian edition, which was sometimes really revealing, as the Russian edition often has more unambiguous formulations.

There is a wonderful and excellently researched documentary from Arte titled The Truth About Lolita. Unfortunately, it is currently not available online. But if you know the lagging public broadcasters, you know that the documentary will certainly resurface soon. If anyone can gain something from this novel, they should definitely watch the documentary. I found it very informative and excellently made. There, in particular, the misinterpretation is addressed that portrays Lolita as a seductress, which seems completely absurd to me. Lolita is a raped child, and anyone reading this book these days encounters nothing but pedophilia and nothing else. It is fascinating how the spirit of the times is reflected in the reception of the book. Doesn’t that make it more relevant than ever?

Conclusion: Nabokov’s Lolita is a masterpiece for several reasons. As a reader, you immerse yourself in the world of thoughts of an intelligent, sensitive, and educated man who is at the same time repulsive in his pedophilia to an extreme degree. Nevertheless, his emotions and reflections become comprehensible to the reader and are consistent in a frightening way. Artfully, Nabokov has portrayed, with great depth, wit, and numerous literary allusions, a relationship that is cruel, that depicts the abuse of a child, and yet is neither vulgar nor superficial. The protagonist tries to win the reader over to his side, and precisely the fact that he wants to present himself in a good light and justify his deed gives the story another layer. As a reader, you perceive all the inconsistencies between the lines and sense as the novel progresses what kind of cruelty toward a child is being exercised beneath the thin, embellished veneer of emotions. A book that fascinated me, that I could hardly put down, and that resonates long afterward. The solid edition from Rowohlt Verlag is very high quality and comes with numerous notes and afterwords that I found very enriching. A wonderful book, a masterpiece, a reading experience that does to the reader exactly what a book should do.

Book Information: Lolita • Vladimir Nabokov • Rowohlt Verlag • 720 Pages • ISBN 9783498046460

Als weiterführende Lektüre empfehle ich “LOLITA LESEN IN TEHERAN”, eine Auseinandersetzung nicht nur mit dem immergrünen Thema “Frauen und Männer” (z.B. Mullahs), sondern auch mit dem gerade in Deutschland hochaktuellen Thema Meinungs- und Informationsfreiheit.

While I would hesitate to characterize Lolita as a masterpiece, I find myself in agreement with several of the insights and perspectives you have articulated. Admittedly, I approach the topic of the sexualization of young girls with a recognized personal bias. Nabokov’s work reveals a clear influence from Edgar Allan Poe—a connection that is readily apparent to readers familiar with Poe’s writing. Humbert, while undoubtedly a delusional pedophile, is also distinctly characterized by his intellectual sophistication. He is the king of justification. Nabokov’s Lolita is replete with allusions to a range of canonical authors, including Shakespeare, Joyce, and Flaubert. It may be this intricate web of literary references that renders the novel somewhat palatable—the aesthetic complexity serving as a kind of intellectual buffer against the disturbing nature of its central theme. Ultimately, it is this dissonance between Nabokov’s prose and the novel’s disturbing subject matter that leaves me less impressed than unsettled, questioning whether literary brilliance can—or should—redeem moral transgression.