20 unusual gift ideas for book lovers, bookworms, bookworms and frequent readers

There are books that trigger something within you, that give your own view of the world a new direction. Such a book doesn’t fall into one’s hands very often, and when it does, it’s a pleasure to read and an incredible enrichment for oneself. Sometimes it’s just certain aspects that fascinate, sometimes a series of elements that seem novel or even shake your worldview. Today I want to present a few books that fall into this category for me and recommend literature that is very much worth reading and broadens one’s horizons in one way or another. So look forward to discovering what you’ll find in this article.

Before I begin, a few words about the rather overblown title of this post. I think every book changes and influences you — after all, you spend several hours with it. Some evenings of reading have only a small or almost no influence at all, for example when you read in a direction you’ve already explored thoroughly. Or when you reach for a light novel to relax. What book can truly change a person? Every book and none — it’s entirely individual. In that context, my sensational title shouldn’t be taken too seriously. There are no books that everyone should have read. And for me, there are also no books that have completely changed my life. This selection includes books that provide food for thought, that also hold surprises in their content, and that have remained vividly in my memory. Of course, this is all entirely subjective. But now, on to my fine selection, which will hopefully serve as an inspiration. Don’t forget: you really should read them right now so your life changes completely.

The Order of Time by Carlo Rovelli

I’ve read several books by Carlo Rovelli. I enjoy secondary literature about physics and philosophy because it’s truly entertaining, and the various interpretations of individual disciplines are also very much tied to the author. Rovelli writes in a pleasant and entertaining way, and his books always have a special idea — a point to make. In The Order of Time, the central message is that time, as we think of it, doesn’t actually exist. Rovelli shows in the first part why there is no linear time that flows the same everywhere, and why there can be no universal simultaneity in the universe. In the second part, he describes what the world looks like without time, and in the final part, he draws conclusions from this. I have to admit, I don’t remember many of the book’s details — which is great, because that means I can and will read it again. What has stayed with me, though: our concept of time is wrong. It isn’t universally valid, and there is no simultaneity in this infinitely large universe. When you read that people might discover life on exoplanets with the James Webb Telescope, it’s not just that this life may have long since gone extinct due to the vast distances involved — no, that other world, if it ever existed, was never running in sync with ours. It’s not that, at this very moment, an alien somewhere far away is walking around on its planet, because there is no synchrony. A truly fascinating thought that keeps you pondering long after reading.

Novellas by Guy de Maupassant

I love Maupassant, and I’ve devoured his novels and novellas. He has a wonderfully clear style, and in his stories, he leaves the interpretation entirely up to the reader — unlike authors such as Balzac, he refrains from life lessons or clever sayings. His novellas often leave the reader hanging, and only after finishing them does one realize what kind of story it truly was. Why does Maupassant appear in this list? Quite simply: he wrote these books in the late 19th century — which is a while ago. Two world wars separate us from that century, as well as numerous major inventions, the whole crazy digitalization, and the societal transformation brought by the Internet. We all feel so modern now, as if everything has changed and humanity has evolved — after all, at least in Europe, there are democracies, education, and science that have enlightened us all. But when you read Maupassant’s novellas, you realize that people more than 100 years ago thought of themselves in exactly the same way. They too considered themselves progressive and utterly modern. What the novellas capture and reflect are events and human reactions that could just as well come from our own time. In one story, a woman tries to commit a small insurance fraud — a trifle — just to see what she can get away with. In another, an adult son and his wife believe his mother has died, and that very night they clear out her apartment because they fear the other siblings might take her possessions. Unfortunately, the mother isn’t dead and wakes up the next day. Those who read these novellas — which expose people and society in a reconciliatory yet initially bracing way — will realize how little humanity has changed in the past 150 years and how appropriate a certain measure of humility would be. These books are read far too rarely; if they were read more, today’s arrogance would quickly fade away.

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

The book The Count of Monte Cristo and its plot are known to almost everyone. I love this book, and I even had it made as a luxury unique edition. Why does it appear in this list? For one, it’s a wonderful adventure that I will never forget — how Edmond Dantès escapes from Château d’If, the moment he looks down upon Rome at night, his encounters with various characters. These and many other scenes are burned into my memory and appear before my mind’s eye almost like personal memories. But there’s another reason it’s included. It also touches on fundamental human thought — questions of justice, of what is morally acceptable and what isn’t. When the Count sits with his two young guests on the balcony in Rome, witnessing an execution, that scene doesn’t just exist to move the plot forward. The Count ensures one of the condemned men is pardoned. Only when the second man learns of this pardon does he lose his stoic composure and completely breaks down. A typically human reaction — people can endure anything as long as enough others endure it too. It’s precisely scenes like this that stir me, and they come to mind whenever I see similar patterns in everyday life, reminding me of books like this masterpiece by Dumas. The Count of Monte Cristo is full of such abstract reflections on human nature.

The Power of Persuasion by Robert Levine

During my studies, I took a semester of social psychology. Based on that, this nonfiction book didn’t hold many surprises. But it absolutely belongs in this list. I think there are numerous books of this kind — so this one stands as an example; it probably doesn’t matter which you choose. In The Power of Persuasion, it’s all about the many manipulation techniques we encounter daily. It starts with the classic supermarket trick — the warm, brightly lit, fresh-looking fruit and vegetable section at the entrance designed to put us in a spending mood. Or priming, which puts our brains into a receptive state, or the old sales trick of offering cheap, mid-priced, and extremely expensive products so that buyers choose the one in the middle — the one that’s meant to sell. In short, a whole bag of tricks through which we’re manipulated in everyday life — and by which we manipulate ourselves. It’s a very enlightening book that leaves its mark on the reader. I now pause at free samples, and I immediately make for the exit when I meet an overly charming salesperson — just to give two examples.

Oblomov by Ivan Goncharov

Another truly great classic — but in these books, you encounter ideas that profoundly influence you. Which is no wonder, since these works have survived through the centuries for a reason. Oblomov contains many fascinating elements, but it appears here for a specific reason: it’s a wonderful character study showing how childhood and its experiences span an entire lifetime. Or, in the words of Irène Némirovsky: “You don’t forgive your childhood. An unhappy childhood is like a soul that has died without a funeral. It groans for all eternity.”

The quote sounds a bit dark, but Oblomov is by no means a gloomy book — in fact, I remember it as being very humorous. Oblomov is a shockingly lazy nobleman who can’t get off his couch all day (I believe it actually takes him about 100 pages to get up). At first, you wonder what’s wrong with him, but as the story progresses, it becomes clear — you learn more about Oblomov’s past and what makes him who he is. It’s an exaggerated picture, of course, but we too are deeply shaped by our past, our childhood, and the people who have crossed our paths and accompanied us through life. This book makes that tangible and vivid, and for that reason, I’ve never forgotten it.

The White Rose by B. Traven

I’ve already reviewed several books by B. Traven on this blog. He’s a wonderful author with an adventurous life story, and his works are full of remarkable and fascinating ideas. It hardly matters which of his books you pick up — each one is full of thoughts you won’t forget. The White Rose is one that particularly impressed me and that I can most highly recommend. It’s about a hacienda owner who’s robbed of his livelihood by ruthless capitalists. What’s fascinating is that Traven portrays both the life of the simple Indigenous man who owns the hacienda and that of the capitalist who has cunningly climbed the ranks of the economic system. The reader comes to understand why this corporate leader acts as he does — why he must act that way — and that his reality compels him. So what about today’s corporations that exploit resources through fracking without regard for nature or the environment? What about the big food conglomerates making profits with questionable methods? Or the energy crisis brought on by the war in the middle of Europe? Traven finds the right words for these things, and when he describes how his protagonist deliberately triggers a crisis (in the book it’s a coal shortage, not natural gas), it becomes clear that every crisis also has its profiteers who make fortunes from it — and that the panic it creates is unjustified. Anyone who wants to better understand modern politics should absolutely read Traven. Here’s a short quote as a taste of what awaits readers in this book:

Show a worker a twenty-dollar bill, and he’ll instantly become a capitalist. You don’t believe it? Try it. Bonuses work better today than whips ever did.

Sophie’s World by Jostein Gaarder

This book might seem a bit overused. I read it as a young teenager and loved it. It’s certainly not a hidden gem. But for me, it was a revelation — for the first time, I realized how many people had thought deeply about the great questions of existence. After reading it, I went to the library and discovered the philosophy section for myself. I think it’s also a great read for adults because it captures that childlike, curious wonder while tying it to humanity’s big philosophical questions. It’s a wonderful overview of the history of philosophy and, without a doubt, much more entertaining than the equally overexposed introductory classic The Philosophical Backstairs (Die philosophische Hintertreppe). If you haven’t thought about the fundamentals of life for a long time and don’t know this book, you can confidently reach for it. And it’s also a great recommendation for children — I think it’s suitable from around age 14.

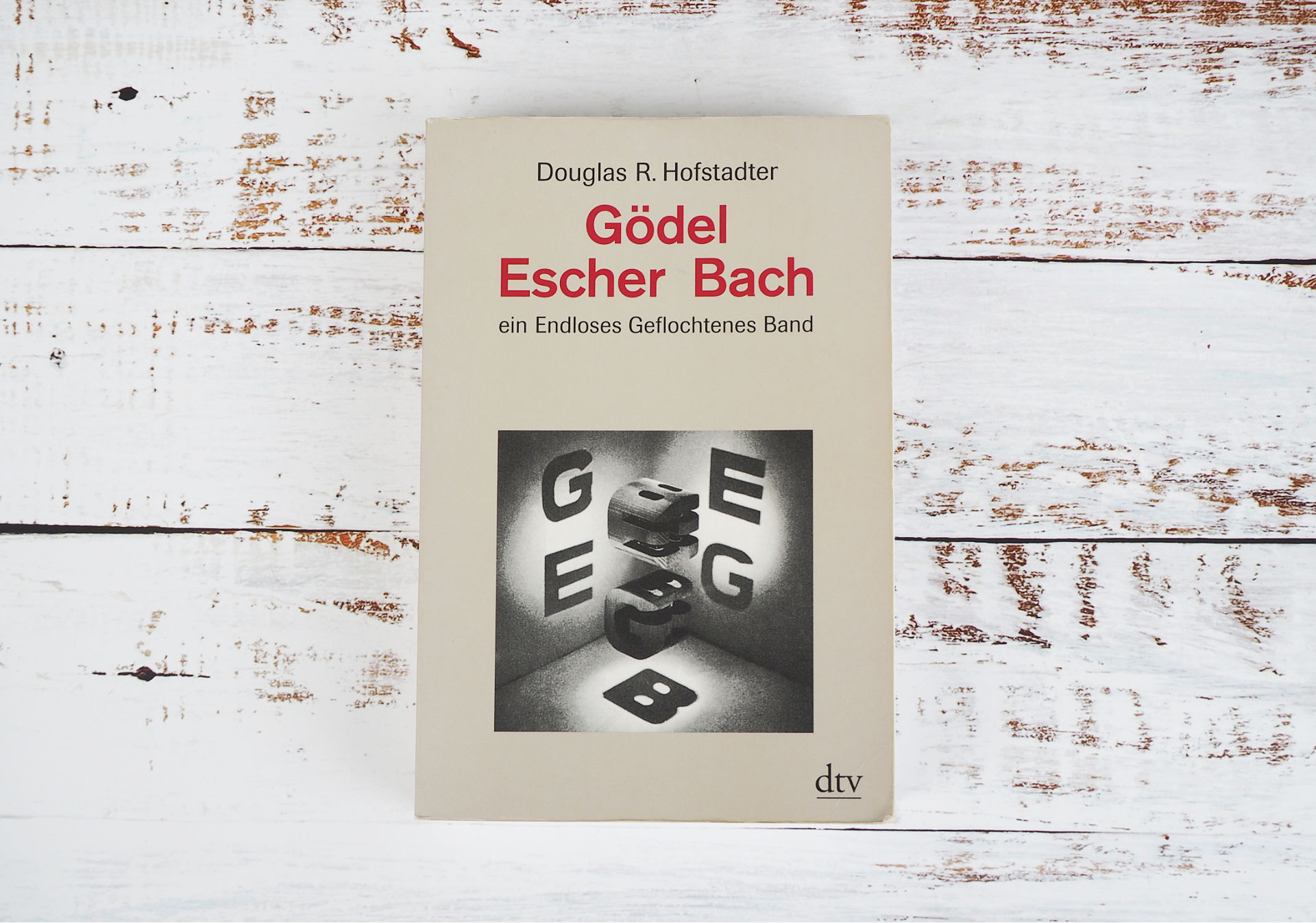

Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid by Douglas Hofstadter

This book was a recommendation from my professor of theoretical computer science. I really liked him and often chatted with him — he embodied everything you expect from a classic professor. Unfortunately, he smoked cigarettes instead of a pipe. Anyway, he was always disappointed that Theoretical Computer Science II never took place because everyone had already lost their minds in Part I. I found it all fascinating because the major questions of theoretical computer science — for example, the halting problem of Turing machines or the P vs. NP problem — are closely linked to mathematics. Concepts like countability and uncountability of sets, Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, and set theory’s exploration of infinity are all connected. This book takes the topic even further — showing links between these ideas, the fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach, and the paradoxical, mind-bending art of M. C. Escher. Hofstadter calls them “strange loops.” What fascinated me most was the connection he draws to the human brain, asking (at least between the lines) to what extent the brain might also be affected by these “strange loops.” Perhaps the limits of computability and complexity theory also apply to the brain in some way. The synchronization of neurons and the generation of mental images are among the topics he explores. This book contains so many thoughts and ideas that it set off a firework of reflections in my mind, leading me to read many more books on the subject. Gödel, Escher, Bach is a masterpiece — and one of the books on this list I most highly recommend, even though it’s certainly a challenge for anyone who isn’t a computer science nerd.

Black Swans by Gaito Gazdanov

Regular readers of my blog know that I love Gazdanov’s books. But why is he included in this article? In fact, it doesn’t really matter which book you choose — his other novels are also clear recommendations. Black Swans is a collection of short stories and, thanks to its variety, a great starting point. Gazdanov’s works fit perfectly here because both his characters — and he himself, as a result of his forced exile — always occupy the role of outsiders. In his works, you encounter people who stand apart from society and see the world through a unique lens. Characters who seem alien at first, yet you can still empathize with them. Gazdanov always touches on philosophical themes and portrays characters with deeply individual, authentic traits. The impulse his stories give you as a reader is subtle and latent, but it lingers — gently shifting your perspective, broadening your horizons in a quiet, profound way.

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

I admit, War and Peace is, of course, a bit overexposed due to its fame. But that doesn’t matter — it’s a masterpiece. It’s so broad in scope that you can’t read it without thinking, without reflecting. And if you don’t like Tolstoy, you’ll still think about it — just to argue against him. Many aspects of it have stuck with me, and I’ve often recalled scenes from this epic in various situations in my life. On one side, there are the two main characters, Andrei Bolkonsky and Pierre Bezukhov. Both go through a range of life situations, trying themselves out in different ways, each searching for the meaning of life. I found this fascinating, and it naturally raises the question of what drives oneself — and how much of oneself one sees in them. I also found Tolstoy’s philosophical reflections on history gripping, even when they become lengthy. When he explains that the great and powerful are in fact heavily constrained in their freedom and lack the freedom of choice one might assume, it’s entirely plausible. Or when he describes that it wasn’t Napoleon who took the lead in conquering Europe, but rather the people of that time — that society itself brought him forth — it makes sense. Whether or not that’s true isn’t the point; it makes you think. And in light of current geopolitics, these are important thoughts that help you see things from another perspective. Of course, there’s much more in the book — but even for these reasons alone, it’s an essential read that belongs on this list.

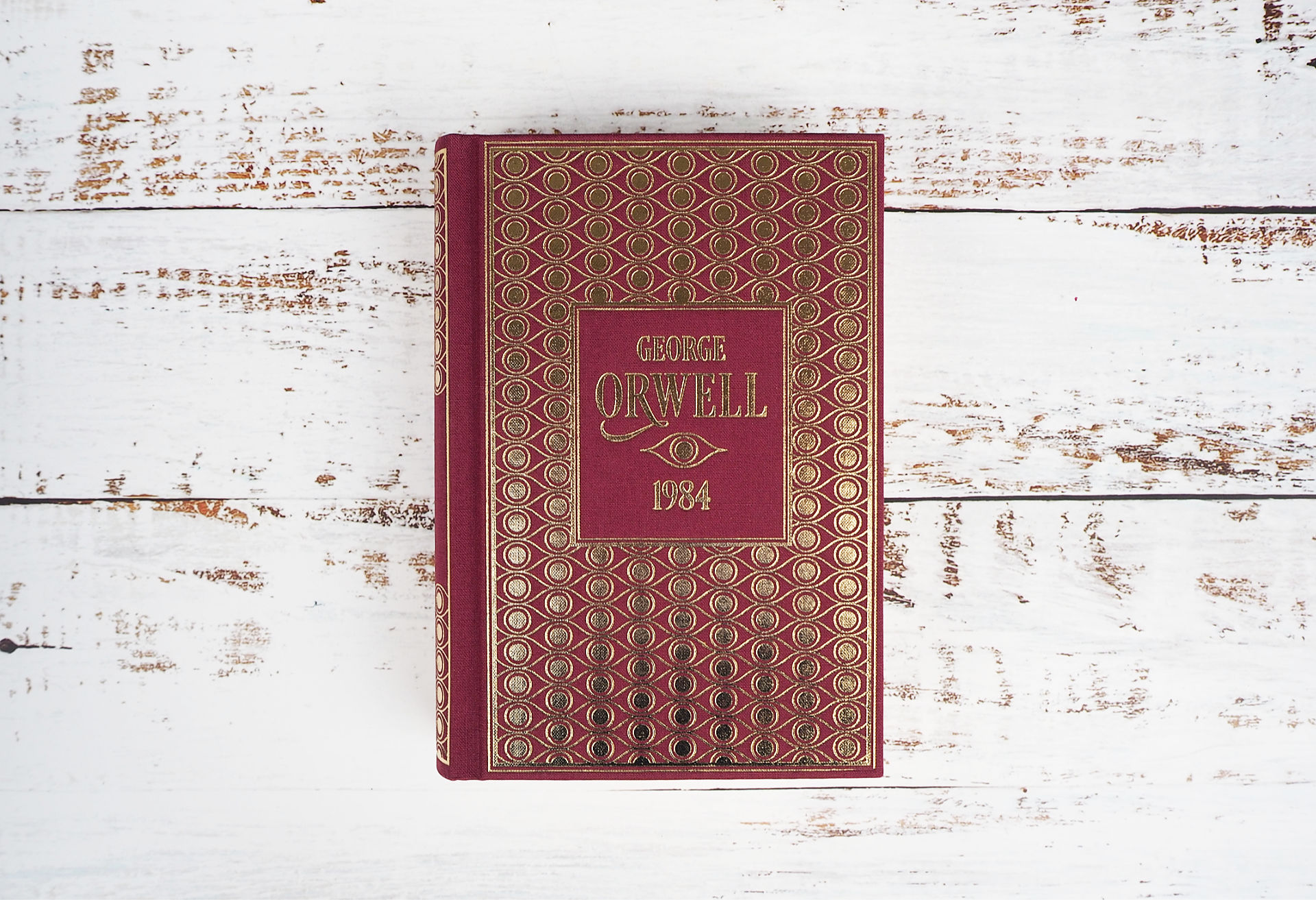

Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

I think Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell can’t be recommended often enough. Considering what happens today with the data of billions of people — many of whom handle it thoughtlessly — this book feels more relevant than ever. In some countries, it even reads more like a manual than a warning. Orwell doesn’t just depict total surveillance as a dystopia — he constructs a society that has reached a stable state but one that works against the well-being of its people. Concepts like “doublethink” or the way the Party manipulates language to control thought (in line with Wittgenstein’s “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world”) are shocking and enlightening at the same time. Anyone observing how language is being changed today will realize how current this book still is. I don’t think anyone can read Nineteen Eighty-Four and remain unmoved. The book only entered the public domain a few years ago, leading to numerous new translations. I used to have an old, battered copy that I (fortunately) can no longer find — which gave me the perfect excuse to buy a beautiful new edition from Nikol Verlag.

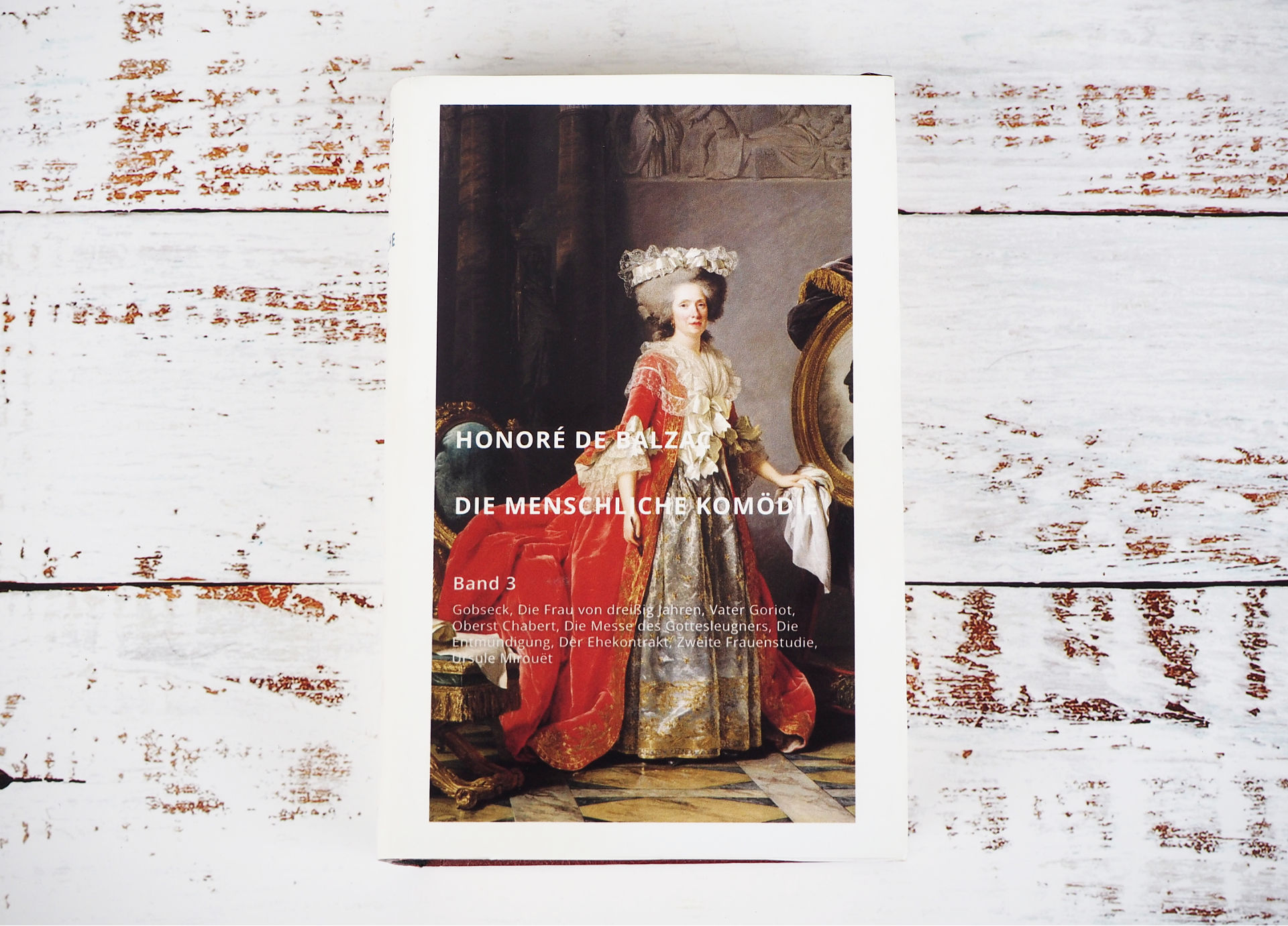

The Human Comedy by Honoré de Balzac

The best comes last. I love Honoré de Balzac, and I’ve read more of his work than that of any other author. His life’s work, The Human Comedy, is unsurpassed; his influence on literature — on the authors of his time and those that followed — is undeniable. His oeuvre is monumental, and his novels, then as now, fascinate, entertain, and are full of philosophical insight. With foresight and relevance that transcend his era — the French Restoration — his works portray human thought and behavior in an abstract, universal way. As an introduction, I highly recommend Father Goriot, which provides a wonderful entry into his body of work and conveys countless inspiring ideas in an entertaining way. Time and again, while reading his books, I’ve found myself thinking: “That’s exactly how it is.” He captures the human mind, its patterns of thought and behavior, perfectly. Of course, he deliberately exaggerates for entertainment, but he also reveals how people have always functioned. You often see headlines in the cultural pages like “Why It’s Worth Reading Balzac in Times of Crisis.” Balzac wanted to become rich all his life, tried everything, and this ambition is reflected in his books. When he describes how César Birotteau becomes a victim of real estate speculation, it could easily come from today. Or when he portrays bankers and aristocrats scheming and chasing profits, and how characters repeatedly try to break through the social layers like onion skins — it’s entertaining, fascinating, and full of insights you can’t easily shake off. Read Balzac — that’s all that needs to be said.

Conclusion: I hope you enjoyed my list and that you’ve found a few good book recommendations. Feel free to share the books that have inspired you, that hold a special place for you, and that have influenced your thinking. I’d love to hear such heartfelt and experience-based recommendations — just like this selection.

Hallo Tobias,

vielen Dank für die vielen schönen Tipps! Ich sehe schon, dass ich mich mit einigen Dingen auf jeden Fall selbst beschenken muss. :)

Viele Grüße

Birgit

Hallo Tobias,

Da sind wirklich schöne Sachen für bibliophile Menschen dabei.

Die Buchbinderei und die Bücher von Verlag Mare muß ich mir genauer ansehen.

Danke für diesen Beitrag und deinen wertvollen Blog !!!

Viele Grüße

Andreas

Danke dir! Meine Freundin ist eine Leseratte und schreibt auch selber Kurzgeschichten und co. Letztes Jahr habe ich ihre Kurzgeschichten als Buch drucken lassen und ein Coverdesign erstellt und davon ein paar Kopien gemacht, sodass jeder ihrer Freundinnen eins hat. Jetzt weiß ich nicht mehr, wie ich das noch toppen kann, deswegen danke für die Inspo!