4 3 2 1 • Paul Auster

After a long time, I finally picked up a contemporary book again and read something from this millennium—which doesn’t happen all that often. Paul Auster’s last novel, 4 3 2 1, was driven quite energetically through the book-blogger village in 2017, shortly after its publication. That alone usually isn’t enough to lure me out from behind the stove. But in this case I found the book’s concept very inventive and intriguing. Whether the read was worth it—or whether Auster once again drove me back into the arms of the splendid authors of past centuries—you’ll find out in this post.

4 3 2 1 is about Archie Ferguson, and the novel begins with Archie’s grandparents and parents and then goes on to describe his life—specifically his youth. However, and this is the special, imaginative twist: not in a single version, but in four different renditions. Four different ways Archie’s life could have unfolded; four different possibilities for how his path might develop—or did develop. Archie grows up in Newark, New Jersey, close to New York, and the novel spans the 1950s and 1960s.

Archie’s background—his parents and his origins as the grandson of a Jewish immigrant from Russia—is, of course, identical in all four versions. But then the four life paths branch off, and both his environment and Archie himself experience very different things; their lives are shaped by entirely different influences, strokes of fate, and changes. As readers, we always follow Archie from a narrator’s perspective: how he thinks and feels; how, through his eyes, we get to know the people around him—his parents, family, friends, and loves. These four versions of Archie’s life are not presented one after the other in isolation, but interwoven, arranged in temporal parallel. You always read a set of four chapters, alternating between the four narrative strands, which thus unfold in parallel time—but in different variants. With each chapter, the differences between the various Fergusons grow. It’s an interesting arrangement that, conceptually, recalls Bach’s fugues a little. Either you listen to the entire melody of the book and get a blurred composite image of all the individual Archies, or you try to isolate the four lives mentally and lose that abstract, overarching view of the protagonist. In truth, you can’t really do that, so the fugue comparison may be a bit off—you’re always spoon-fed a blended version of all four Archies. That, in part, is the book’s appeal. I liked this arrangement a lot.

I also really liked the setting—the Newark, New Jersey, and New York of the fifties and sixties. I’ve read very little about that period, so I found it exciting how Auster tells the very individual developments of the four variations while the political, social, and societal backdrop remains a constant, influencing Archie’s different traits in different ways. The events of the time—the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, the ’68 movement, student protests, race riots, the assassination of Kennedy—all the major political developments are, of course, constant, the same in every variant, and so the reader learns from different perspectives how these changes reverberated through society then. In one variation, Archie is intensely involved in the Newark uprisings; in another, in the protests at Columbia University.

I also loved how Auster develops Archie’s personality. His experiences—what he lives through, his social environment—shape his nature and character, and so he is a different person in each of the four versions. And yet, not entirely: his strengths and weaknesses are, in many respects, similar. Auster seems to balance what a person’s genes provide with what life experiences and other people’s influences bring. He does this quite well. Archie is always drawn to art, literature, and film, and in every variant he writes in some form. You can recognize the core of his personality in each of the stories, as different as he otherwise appears. Sports are always one of Archie’s passions, too, and Auster weaves that into the novel nicely—something secondary, yet something that drives, enriches, and interests Archie.

Overall, Auster focuses on Archie’s childhood and youth; the novel does not cover his entire life. I didn’t expect that at first. But youth—the feelings, uncertainties, the difficulties of growing up and finding oneself—is something Auster depicts very well. I found it convincing, and he communicates Archie’s internal conflicts at many points with great clarity. His characters felt consistently plausible and realistic to me—not only Archie, but also his parents and friends.

A key element of the novel lies in these four variations—something that really made me think: how much life depends on coincidence, on the people around us, and on politics. How many different ways one’s own life might have unfolded, and how these what-ifs belong to life just as much as what actually happened. There’s a hint of fatalism in that, but not entirely, because in every variation it’s also Archie’s own decisions that steer his life in different directions. The question that arises—the one everyone probably asks at some point—is what the different versions of one’s life might have looked like. And perhaps what didn’t happen is more present than we consciously perceive. This always makes me think of the infinity Nietzsche postulated: that in an infinite universe, anything with a probability greater than zero (no matter how small) will occur at some point—indeed, infinitely often. That would mean you live one possible version, but, assuming the universe is infinite, you will also experience all the other possible branches. From that perspective, Auster’s four developments are vanishingly few.

The book moved me again and again in places—especially its sense of youth, that everything-is-possible feeling. But on the whole, 4 3 2 1 didn’t excite me as much as other books that got under my skin. Archie still felt somehow too distant to me. On the one hand, the narrative mode—while offering good insight into Archie’s thoughts and feelings—often struck me as somewhat cool and detached. I didn’t truly root for the protagonist; no intense bond formed between me and Archie. On the other hand, I could identify with him only to a limited extent, and all four Archies had little in common with me, so my empathy was limited.

These interwoven strands—four variations that alternate in constant rotation—also disrupt the reading flow each time. I repeatedly found myself asking which version I was in and what had just happened before. That effect is likely intended to create precisely this blending, but it isn’t necessarily conducive to the reading experience. You do end up flipping back now and then to check what last happened in the given thread.

In terms of language, you can tell the sentences have been polished, and there are some very effective constructions—such as long, unending paragraphs when, for example, a character’s breathless litany of self-doubt is described. Or enumerations when Auster wants to capture different facets of a situation. Elsewhere, he prefaces sections with italicized keywords to characterize particular points. These are lovely, distinctive devices, but I still often found the phrasing less poetic and sonorous than I’d hoped—more straightforward. In that respect I expected more. When I think, for instance, of Richard Powers’s The Time of Our Singing, I was repeatedly blown away by the rhythm and melody of the language. There are passages like that in Auster’s book, too, but sadly far too few. I don’t want to withhold one such splendid sentence from you (though it isn’t complete—it goes much further; this is only the beginning):

“A white South African woman with the dark complexion of a North African, older, deeper roots in the deserts of the Middle East overlaid by Eastern European roots, the exotic Jewess of Germanic and Nordic literature, the gypsy girl from nineteenth-century operas and Technicolor films, Esmeralda, Bathsheba, and Desdemona in one, the black fire of her curled, unruly hair like a crown on her head, delicate-boned and narrow-hipped, slightly sloping shoulders and bent neck when she took notes in class, languid movements, never hectic or annoyed, calm, gentle and calm, not the Levantine seductress she seemed to be but a solid girl full of warmth, in many respects the most normal girl Ferguson had ever felt drawn to, […]”

p. 672

Paul Auster was born in Newark in 1947, has published numerous books, and is a fixture of American literature. He has also written poetry and essays, worked as a translator, and lived in France for a time. Reading Auster’s biography, it’s clear that this novel is highly autobiographical and that he has a great deal in common with Archie. His passion for sports, films, books; his birthplace; the fact that the ’50s and ’60s were also the years of his childhood and youth; that he too was deeply impressed by Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment; that he studied at Columbia University; Auster describes himself as just as shy as his Archie—and there are many more parallels. Considering that Auster published this book at nearly seventy, it’s more than a simple story. While reading, the book often felt like a retrospective, a recapitulation, with a constant hint of melancholy. Even at the beginning of a bright phase in Archie’s life—when something goes well—I always sensed transience, likely amplified by the narrative compression. Archie often seems far too reflective and wise for a teenage boy.

If you’d like to learn more about the background, about Paul Auster and this novel, I can recommend an excellent ARTE documentary that I watched right after finishing the book (note: the documentary contains many spoilers, so watch it only after reading). It makes clear, again, how strongly Archie is bound up with his creator. And Auster talks about how he writes, sharing a few behind-the-scenes insights. I always find that fascinating. You can also sense that Auster is a rather melancholic person—something I strongly felt in his book.

After watching the documentary—the interviews with him and with his wife—I also understood why the book didn’t fully grab me; why Archie, and thus Auster, didn’t come as close to me as a work of this scope should. His whole mindset, his way of thinking, his way of seeing and describing the world is that of an artist. Of course every book is art, and of course I’m drawn to many facets of it. But I’m also a child of ratio—wedded to a prosaic, pragmatic, unsentimental view of the world, at which a true artist would probably only shake his head. But so what—good! With books, we encounter all kinds of people: those we fall in love with from the first line, and those whose worldview differs from our own—and I enjoy that in every book.

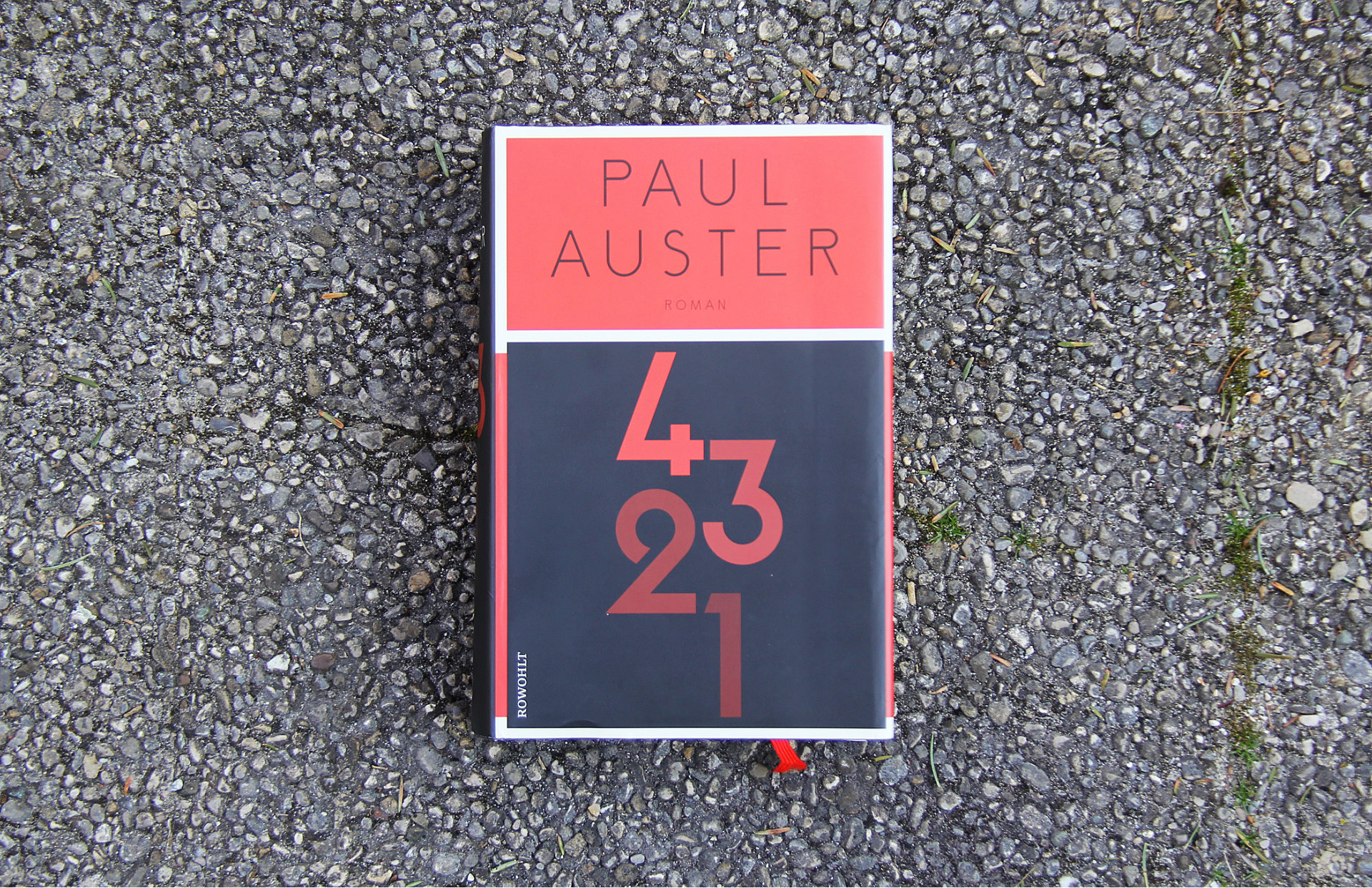

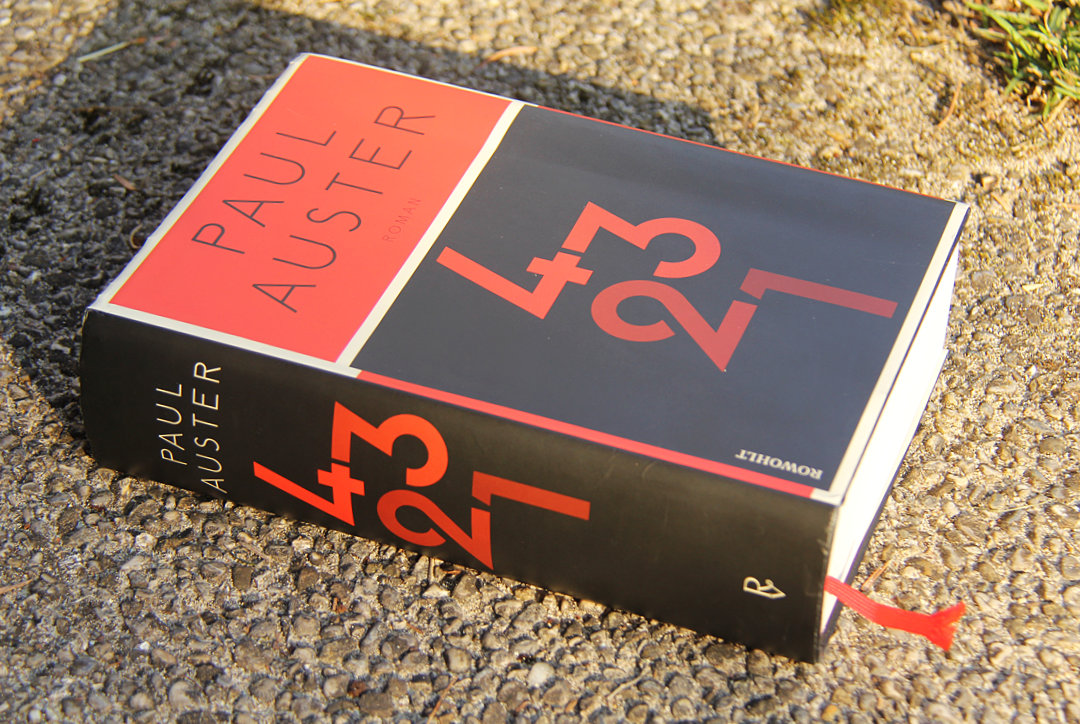

The edition itself was named one of the most beautiful German books of 2017 by the Stiftung Buchkunst, and of course I got the hardcover. But I can’t quite follow the decision. I expected a truly splendid, lavishly produced novel, but I find the design rather ordinary and not particularly outstanding. So you can safely opt for the paperback, since the features praised by the Stiftung Buchkunst jury are present in the paperback as well.

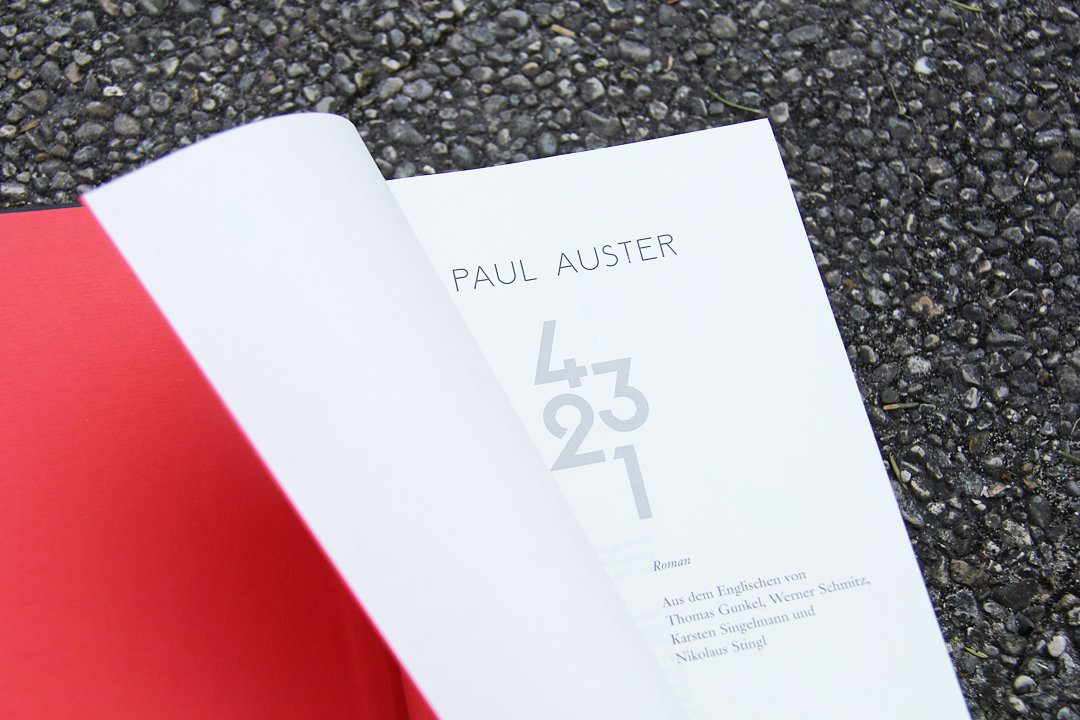

I also find it interesting that it took four translators to bring the book into German. I found the answer in the FAZ review: the aim was apparently to publish the book in Germany at the same time as the original, and that wouldn’t have been feasible if only his regular translator, Werner Schmitz, had worked on it. According to the FAZ article, the translators weren’t each given a single Archie version, but worked according to their availability.

Conclusion: Auster’s expansive novel about four variations of Archie Ferguson’s life is a successful book that offers a very personal view of America in the fifties and sixties. Mapping out the different possibilities of one human life is an unusual and fascinating idea that Auster executes excellently. With its occasionally unconventional stylistic devices and the detailed attention to its many convincingly drawn characters, the novel entertained me consistently well. It didn’t utterly captivate me, though. I simply didn’t develop an intense bond with its protagonist, and I found too few sentences truly sonorous and poetic. Still, it’s undoubtedly a major achievement, and the novel’s autobiographical traits lend it great authenticity and depth. A novel well worth reading—one that stirred quite a few thoughts and feelings in me.

Book Information: 4 3 2 1 • Paul Auster • Rowohlt Buchverlag • 1264 pages • ISBN 9783498000974

Und wieder, ich glaube ich muss dieses Buch echt noch lesen, es reizt mich schon seit langem, danke das du mich noch einmal daran erinnert hast.

Ich bin ganz auf der Linie dieser Rezension. Mir hat das Buch durchaus gefallen, es hat sich gelohnt, es zu lesen, aber dennoch mischt sich auch ein wenig Enttäuschung in die Beurteilung. Das literarische Experiment (vier mögliche Leben nebeneinander bzw. durcheinander) ist interessant und verdient Respekt, ich würde es auch nicht als misslungen bezeichnen. Aber so richtig gelungen … ist es dann auch nicht. Frühere Bücher von Auster haben mir sämtlich besser gefallen. Es ist richtig, man muss immer wieder zurückblättern, um den Durchblick zu behalten, und es gibt unnötige Längen in der Beschreibung. Besonders die Studentenunruhen fand ich zu detailliert und ausführlich beschrieben, da wurde es zuweilen sogar langweilig. Auster ist aber als Autor jederzeit stark genug, um gut und auf hohem Niveau zu unterhalten. Die Aufmachung: ja, in der Tat, nicht wirklich preiswürdig. Aber wen juckt’s ? — es geht ja um den Inhalt.

Lieber Lucien,

“4 3 2 1” war mein erstes Buch von Auster, daher hat mir da der Vergleich gefehlt. Im Vorfeld wurde bei mir aber auch die Messlatte echt hoch gelegt, weil das Buch überall so hoch gelobt wurde und die Erwartung konnte es dann doch nicht erfüllen. Die Längen die du beschreibst, kann ich auch bestätigen. Ich fand diesen ersten Schuhgeschichte von Archie echt langatmig und die hätte es echt nicht gebraucht.

Was die Aufmachung angeht, da war ich natürlich schon angespitzt, durch den Preis der Stiftung Buchkunst. Da habe ich einige wirklich schöne Bücher die ausgezeichnet wurden und um so überraschter war ich, dass dann diese Ausgabe doch so gewöhnlich war. Unterm Strich ist das nicht so schlimm, aber Du weißt ja, gegen ein schmuckes Buch habe ich natürlich nie etwas einzuwenden ;)

Ich finde es interessant, dass ich mit meiner Meinung nicht alleine bin. Ich hätte eher mit dem Gegenteil gerechnet.

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

P.S.: Ich hoffe ja, dass Du wieder aktiv wirst. So ein Buch wie “Die Inseln, auf denen ich strande”, wieder so schick im Mare Verlag, da wär ich wieder dabei ;)

Lieber Tobi,

ich bin sehr aktiv, nur hakt es leider ein wenig bei der Verlagsfindung. Aber irgendwann kommt wieder was, und ich hoffe, es findet dann gute Aufnahme, auch wenn es nicht bei mare ist.

Viele Grüße,

Lucien

Lieber Lucien,

dann drücke ich Dir die Daumen und hoffe, dass Du bald erfolgreich bist. Also ich würd mich über etwas Neues von Dir sehr freuen! “Ein letzter Tag Unendlichkeit” hab ich auch noch sehr gut in Erinnerung.

Herzliche Grüße

Tobi

Ich kann dem nur zustimmen. Als Fan von Austers Romanen war ich bei diesem hin- und hergerissen. Das Was-wäre-wenn-Konzept fand ich eine großartige Idee, habe in der Umsetzung aber auch viele Längen wahrgenommen, die sich bei einem einfachen Handlungsstrang vermutlich nicht eingeschlichen hätten, z. B. schier endlose Passagen, in denen nur ein Baseballspiel beschrieben wird. Und, ja, einen richtigen Bezug konnte ich zu dem Protagonisten (bzw. seinen diversen Ausführungen) ebenfalls nicht aufbauen, wobei ich nur zwei von Archies Versionen richtig glaubwürdig gezeichnet fand – ist aber vielleicht auch Empfindungssache. Der Schluss jedoch, hat mich dann trotz aller Kritik wieder voll gepackt, und damit quasi auch versöhnt.

Vielen Dank jedenfalls für den Beitrag und die zusätzliche Recherche! Das mit den Übersetzern hatte ich mich tatsächlich auch schon gefragt.

Liebe Cathryn,

also ich glaube ich muss doch noch mehr von Auster lesen. Bisher ist das ja mein erstes Buch von ihm und scheinbar gibt es von ihm noch Besseres. Die Baseballspiele gingen sogar noch, obwohl ich mit sowas nicht viel am Hut hab. Aber die Schuhgeschichten, die hat mir gar nicht gefallen, die hätte es nicht gebraucht. Überhaupt alle Romanentwürfe, die von ihm gebracht wurden.

Ich fand schon alle vier Archies ganz gut gelungen, wobei bei mir das im Kopf dann schon ein ganz schöner Matsch war, ich glaube ich könnte sie nicht so isoliert bewerten. Das Ende fand ich aber auch ganz gut, da kann man nichts sagen. Wobei es aber die so deutliche Erklärung nicht unbedingt gebraucht hätte. Aber das Buch ist schon eine Runde Sache.

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Hallo Tobi,

oh genau – die Schuhgeschichte! Die hatte ich schon fast wieder verdrängt :-D. Insgesamt hätte das Buch somit auch gut 300 Seiten kürzer sein können.

Das Autobiografische, das Du oben erwähnt hast, ist übrigens typisch für Auster. Zahlreiche seiner Bücher handeln von Schriftstellern oder New York oder Schriftstellern in New York. Auch der Bezug zu Frankreich ist ein wiederkehrendes Element. In einer seiner Geschichten spielt er als Schriftsteller sogar selbst mit, was dem Ganzen etwas wunderbar Skurriles verleiht. (Das war die New York Triologie, glaube ich). Das macht dann eigentlich auch das aus, was ich an Austers Büchern so mag, zusammen mit diesen Crossing-the-forth-Wall-Momenten wie am Ende in 4321. Weiteres von ihm kann ich Dir da nur empfehlen.

Viele Grüße

Cathryn

Lieber Tobi,

ich muss das Buch wirklich noch lesen! Leider schreckt mich aber die Dicke – und der Umstand, dass ich es dann nicht mit mir herumtragen kann/will – doch etwas ab. Danke für die ausführliche Rezension und den Doku-Tipp. Die werde ich mir Morgenabend, wenn ich Zeit habe, auf jeden Fall anschauen!

Liebe Grüße

Cora

Hi Tobi,

ich finde mich an einigen Stellen in deiner Rezension wieder. Austers Roman habe ich letztes Jahr gelesen, es war auch mein erster Auster und ich war im Großen und Ganzen sehr angetan. Die ellenlangen Aufzählungen und zahlreichen eingeschobenen Nebensätze waren auch mir stellenweise zuviel und zu ausufernd. Bei der Geschichte konnte ich durch einen Trick ganz gut mithalten. Bei größeren Ereignissen seines Lebens habe ich am Buch ein Klebe-Fähnchen-Dingsie (du weißt schon … die Dingsies eben) angebracht – für jedes Kapitel bzw. jede Archie-Version eine andere Farbe. So konnte ich direkt zurückblättern und mir in Erinnerung rufen, welcher Archie das ist. Man sah so auch ganz, welcher Archie wann “aufhört” … was mich jedes Mal sehr getroffen hat. Allerdings brauchte ich die Methode nur am Anfang als die Leben der “Jungs” bzw des Jungen noch sehr ähnlich verliefen, später ging es dann eigentlich ohne. Mit Archie selber bin ich allerdings auch nicht warm geworden. An Empathie mangelte es mir nicht, aber die jugendliche Sexgeilheit nahm mir irgendwann etwas überhand. Ja, es ist ein wichtiges Thema, insbesondere in dem Alter. Aber der Fokus darauf war mir zu stark.

Bei der Ausgabe bin ich aber auch bei dir – ich empfand die deutsche Ausgabe als relativ schmucklos und habe mich für eine englische entschieden, die ich mit den ganzen Menschen(leben) auf dem Cover irgendwie passender fand. So oder so … ein ganz schöner Brocken “Leben”. Danke für das Teilen der Doku, wird geschaut.

Viele Grüße

Lieber Tobi,

War im Netz über Deine Website Lesestunden.de gestolpert. Und schon war ich eine Stunde lang hier gefesselt. :-D

Deine Rezension von Paul Austers 4 3 2 1 ist sehr gelungen. Und ehrlich. Besten Dank! Erinnert mich irgendwie an den Film ‘Mr Nobody’, in welchem der Protagonist drei verschiedene ‘Lebenswege’ beschreibt, jeweils mit einer anderen Lebenspartnerin. Eben, wie sich die kleinen Entscheidungen im Leben auf den gesamten Rest noch auswirken werden.

Ich hätte fast meinen Verlag gebeten, Dir unbescheiden ein Rezensionsexemplar der Lehre vom Unterschied zu übersenden. Dann las ich aber, dass Du eigentlich fast nur Klassiker und die großen Verlagsproduktionen liest. Schade.

Dann bleibe ich halt nur im Kommentarbereich, haha. Trotzdem alles Gute für Deinen schönen Blog, den ich verlinken und dem ich noch lange folgen werde.

Beste Lesestunden wünscht Dir

Mit verbindlicher Empfehlung

Thorsten J. Pattberg, Autor der Lehre vom Unterschied