Time Shelter • Georgi Gospodinov

This novel came as a recommendation, and after the premise sounded so intriguing, I decided to get the book. The author, Georgi Gospodinov, is from Bulgaria, and I believe I have never read a book by a Bulgarian author before. That made me all the more curious about what awaited me here. What kind of idea is this, with the time shelter, and what lies behind it?

The narrator of the book meets a mysterious man named Gaustín, who seems somehow lost in the past. In Zurich, Gaustín opens a clinic for people suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. Across several floors, he recreates rooms that precisely reflect individual decades — for example, several rooms identical in every detail to a 1960s apartment. There, Alzheimer’s patients are accommodated, and the familiar surroundings are meant to stimulate their memory and provide them with a dignified twilight of life. However, Gospodinov goes even further in the book — more and more people, even those who are not ill, wish to lose themselves in the past and visit these clinics. Eventually, the entire society is swept up in this desire, until whole nations decide to retreat into the past.

I still remember the DDR Museum in Berlin, where an entire living room from that era has been recreated. It’s truly fascinating, and I imagine it must be deeply moving when one rediscovers one’s own past in such a space — the countless everyday details such a room evokes, and the reminiscences it triggers. People with Alzheimer’s often lose their more recent memories first, and gradually, like a reverse timeline, even older ones fade away — though childhood memories usually remain the longest. The idea that an environment from one’s childhood or youth could promote well-being and orientation in such patients sounds quite plausible.

Gospodinov describes these rooms and the scenes from the past beautifully. He brings to life those blurred, pastel-colored images, that mood, those moments and fragmented impressions — things I’ve often noticed in myself as well. Essentially, this is a book about the past, collecting reflections on forgetting, transience, remembrance, nostalgia, and the typically human thoughts surrounding them — often told in small, essayistic sections from very different perspectives. I really liked that. The book contains many wonderful ideas, some of which resonated deeply with my own reflections on the subject. I even noted down several quotes because they are so striking.

“The past hides in the afternoons; there, time visibly slows down, dozes off in the corners, blinks like a cat at the light filtering through the thin blinds. It is always afternoon when we remember something — at least for me. Everything depends on the light.”

(p. 59)

This essayistic style is characteristic of the book, and Gospodinov’s approach to time and transience is remarkable. It’s clear that he has done extensive research and packed a lot of thought into the text.

“Memory holds you, traps you in the hard contours of a single person you cannot leave. Forgetting comes to set you free.”

p. 302

I was curious to see how much of Gospodinov’s Bulgarian roots I could find in the book — and indeed, there is a lot of it here. Presumably, much of the novel is autobiographical, as he describes scenes from his life in Bulgaria, often set in the city of Sofia. The broader political events in the story also primarily take place in Bulgaria, which makes sense — it’s the environment he knows best. The reader encounters many references to Bulgaria’s political and historical background, particularly the Soviet-influenced postwar period. It all feels authentic and is quite interesting, especially when he writes about the Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum, where the politician’s embalmed body — like Lenin’s — was once displayed.

The actual plot is rather loose, and the storyline is only faintly developed. There is a framing narrative, but the focus lies on the contemplation of the past in all its facets. For me, that wasn’t enough — I never really formed an emotional connection to either the narrator or Gaustín, nor did I find myself particularly interested in them. That’s a pity, because plot is what carries a reader through a novel, and when it’s too weak, something essential is lost. We tend to remember things best when they’re emotionally charged. So, this wasn’t a book I devoured or became deeply absorbed in.

Stylistically, I didn’t find the novel particularly remarkable — the sentences are simple and straightforward. Some passages are nicely written, but overall, it’s certainly not a linguistic masterpiece. You can tell that the author studied philology, as he includes several references to notable literary works, often mentioning Thomas Mann. However, I found his variation of the famous opening line from Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina rather heavy-handed and flat.

“All stories that have happened resemble one another; every story that has not happened has failed to happen in its own way.”

(p. 58)

Toward the end, the narrative becomes even looser — presumably to suggest that the narrator, too, is forgetting and losing himself in time. But that felt forced, as if Gospodinov wanted to add another layer of meaning to the book. Especially toward the end, it doesn’t really succeed.

In the novel, Gospodinov imagines a European Union where individual countries decide to return to the past. Each nation holds a referendum to choose the decade it wants to live in. He analyzes which country would choose which era, offering explanations and reflections. I found that far-fetched, and the reasoning didn’t convince me either. Yes, it’s meant as a thought experiment within his essayistic exploration of transience — but it’s so unrealistic that it went too far for me. Even the initial idea of the clinics recreating different decades for dementia treatment is already implausible. At least in Germany, such a thing would be utterly far-fetched. Who cares about the elderly here? The pandemic revealed what German society thinks of children and the elderly: nothing. Even the basic humane care of healthy elderly people is barely possible in this country, let alone for those suffering from Alzheimer’s. A clinic like the one described would be a luxury beyond reach. As a single institution in Switzerland, the thought experiment feels realistic — but beyond that, it loses credibility. And I suspect that in other EU countries, the disregard for the weak and the young is no different. That fact alone further undermines the already weak plot.

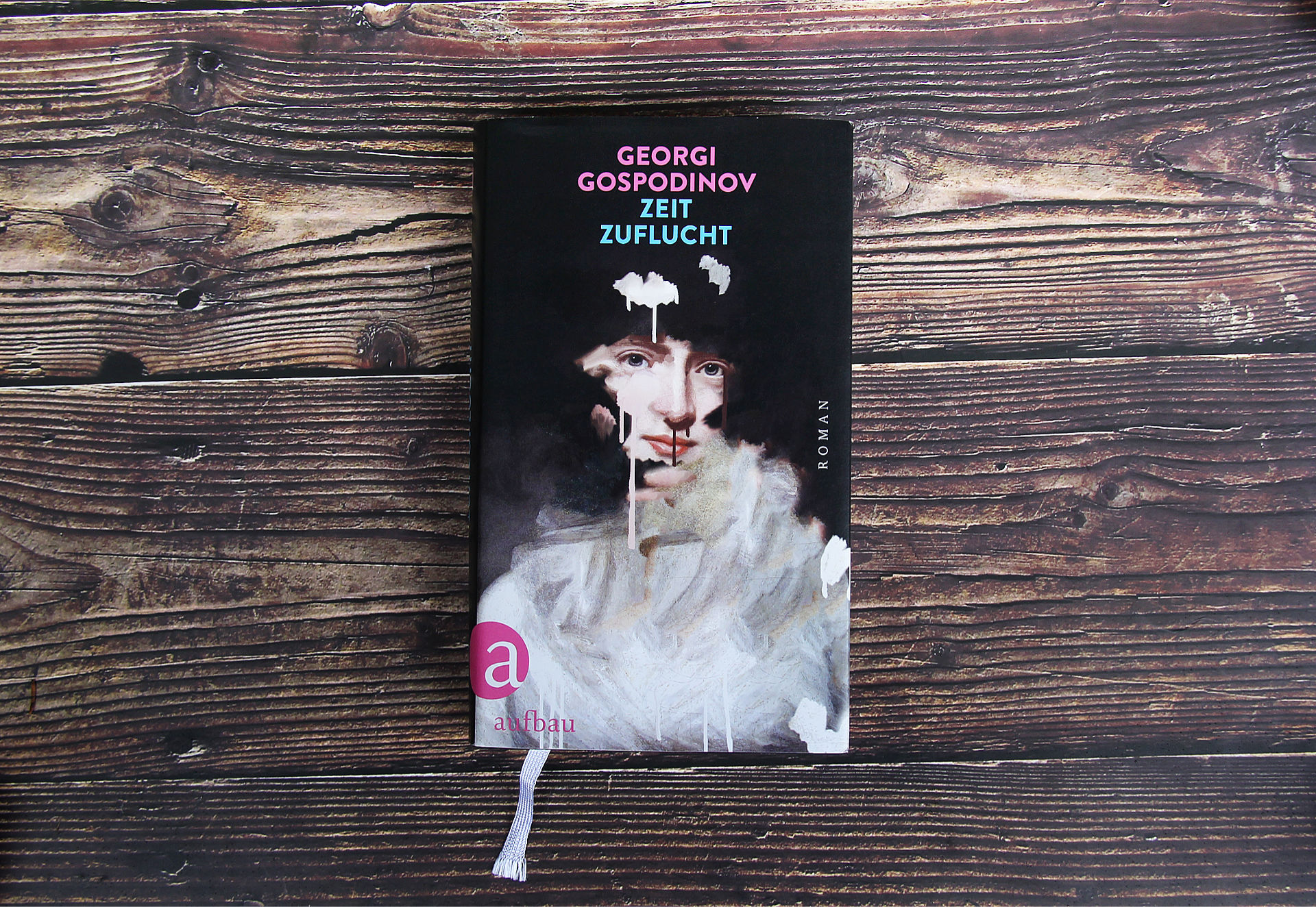

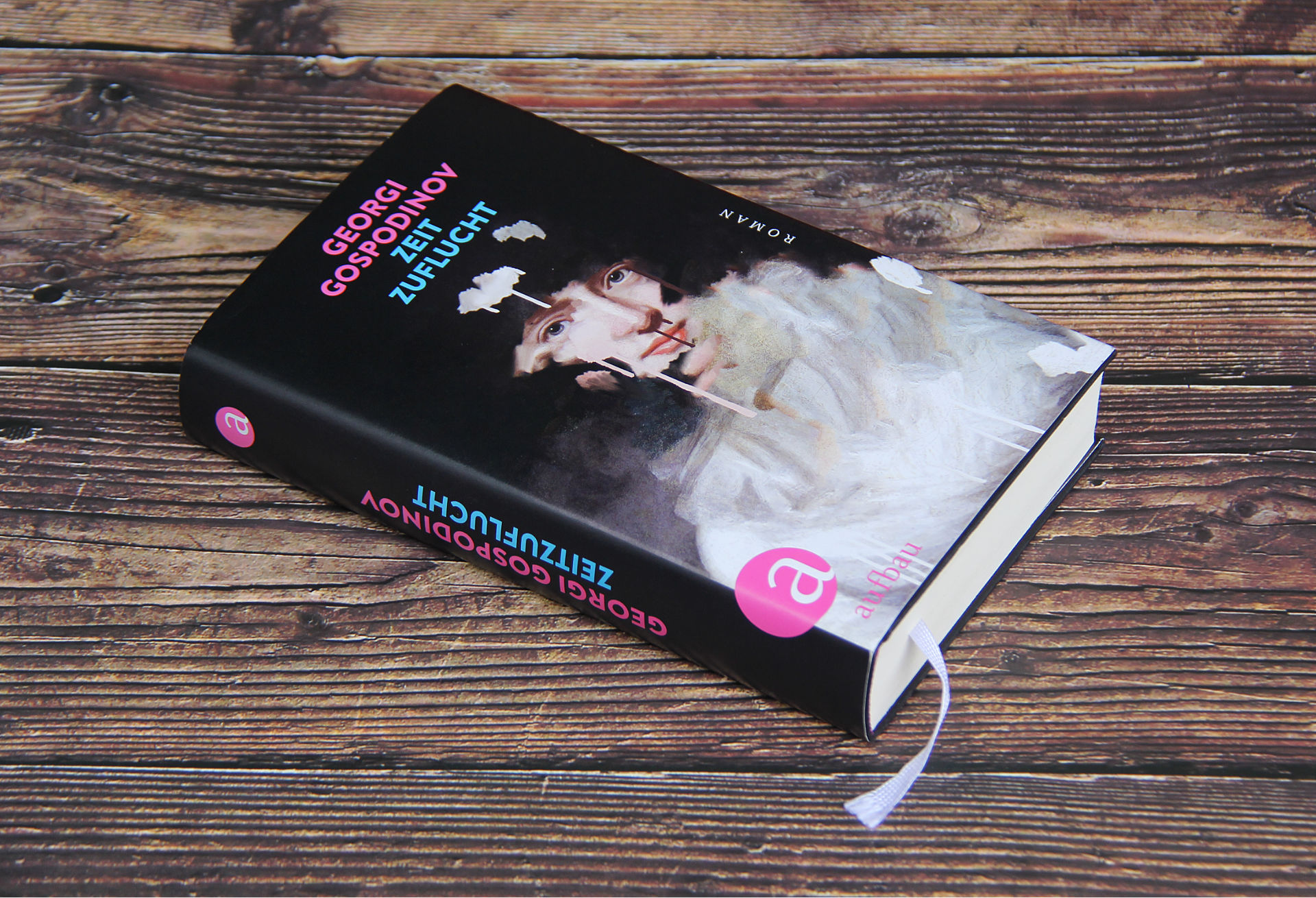

From a design perspective, I really like the book. The cover image looks great, and the typography is well chosen. With its bookmark ribbon and color scheme, it’s visually appealing. However, the actual book — with its black cover and standard glued binding — is entirely average.

Conclusion: The idea behind Time Shelter is unusual and fascinating. A clinic with rooms that could have come straight from different decades, serving as a refuge for both the ill and the nostalgic — that’s a truly extraordinary concept. Gospodinov fills the novel with many thought-provoking reflections on transience, the past, time, forgetting, memory, and nostalgia. At times, it feels more like an essay, with only a faint overarching plot. The story itself is unrealistic, and the characters fail to evoke emotional involvement. Overall, the book left me with mixed feelings. For those fascinated by the past and its many dimensions, it’s worth reading. But those expecting a gripping or immersive story will be disappointed. Time Shelter isn’t a must-read, but you won’t regret reading it either — thanks to its occasionally profound insights.

Book information: Time Shelter • Georgi Gospodinov • Aufbau Verlag • 342 pages • ISBN 9783351038892

Ich habe den Artikel über ‘Zeitzuflucht’ von Georgi Gospodinov auf Lesestunden gelesen und bin begeistert! Die tiefgründige Auseinandersetzung mit der Thematik Zeit und Erinnerungen ist enorm fesselnd. Gospodinovs poetischer Stil und seine Fähigkeit, komplexe Emotionen in gut verständliche Worte zu fassen, machen das Buch zu einem echten Erlebnis. Ich kann es kaum erwarten, die vielen Nuancen und Perspektiven, die er anspricht, selber zu entdecken. Ein absolut empfehlenswerter Beitrag für alle Literaturliebhaber!

Ich habe das Buch auch gelesen und es lässt mich zum Thema Zeit und Erleben nachdenken … und ja, man glaubt sich wirklich zB. an den eigenen Kindheitsort versetzt, wenn man ein ähnliches Bild vor sich hat. Ging mir mal mit den Klassenfotos in der Volksschule so. Ich war mir beinhart sicher, das sei aus unserer eigenen Schule gewesen. War es aber nicht. Es sahen nur alle Kinder irgendwie “gleich” aus.