Moby Dick or The Whale • Herman Melville

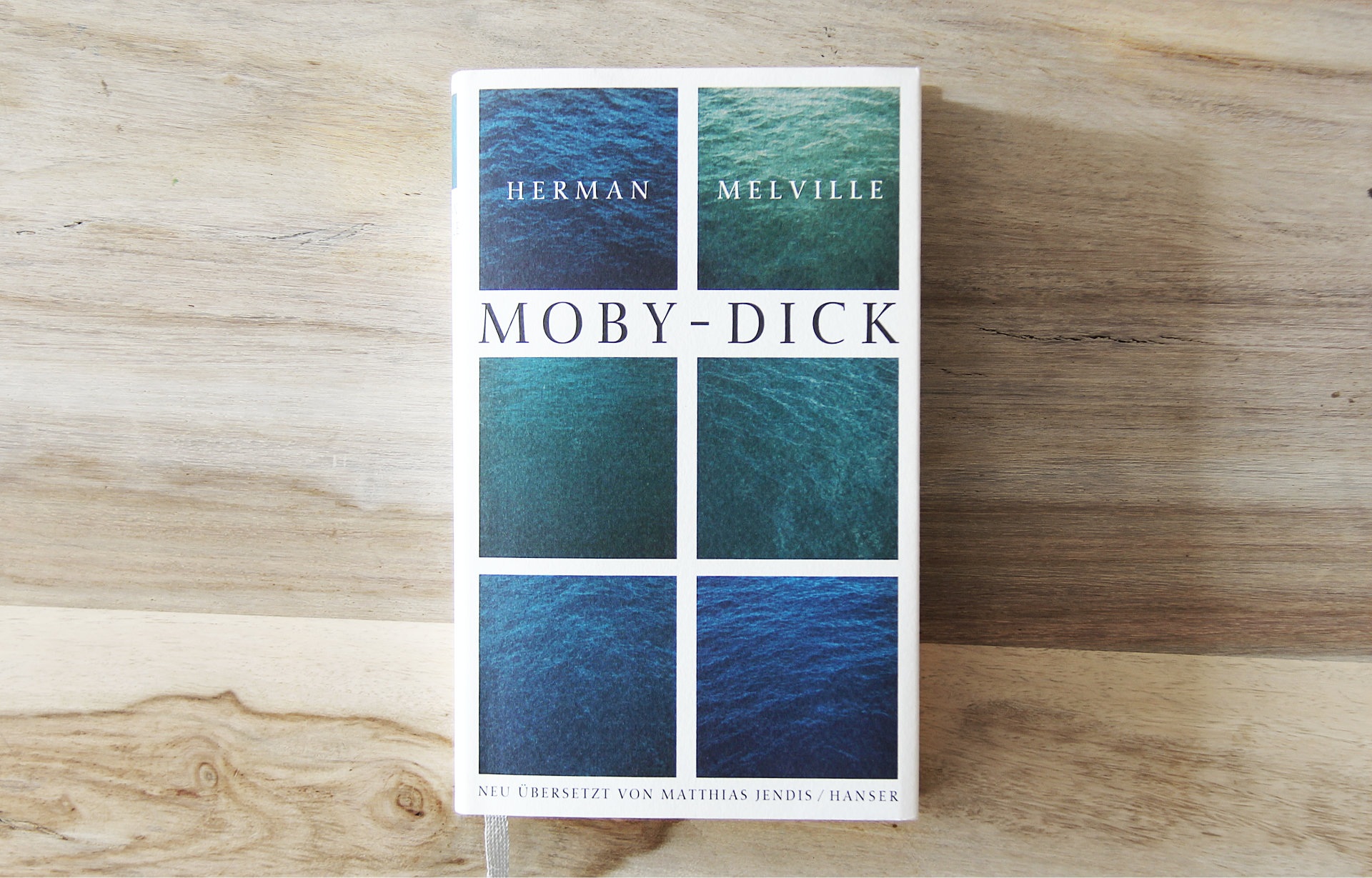

This time I’d like to present a real insider tip. A classic that hardly anyone knows and that I stumbled upon more or less by accident in the depths of the library. Still, the book Moby-Dick is worth a mention. That’s how I would have started my review if a few literary scholars hadn’t rediscovered the book in the 1920s, bringing it to the fame and place in world literature it enjoys more than seventy years after its publication. During Melville’s lifetime, Moby-Dick sold only 3,000 copies. Over the past few months I feel like I’ve bumped into the book exactly those 3,000 times, as it’s available in countless editions and printings. Once again, I went for the handsome edition from Hanser Verlag.

In terms of theme and setting, the book fits perfectly into my wheelhouse: the sea, an adventure on the high seas, a story told from the perspective of an ordinary sailor—and all that in a sleek, newly translated classic. Even so, I set the book aside for a while. At over 850 pages, it’s a substantial read, and this edition is supplemented by around 200 pages of notes and an afterword.

There are countless film adaptations of Moby-Dick, none of which I’ve seen, so beyond the broad strokes on the jacket copy I didn’t really know the plot. The story is told by Ishmael, an ordinary foremast hand—an ordinary seaman quartered in the less hospitable forward part of the ship. He signs on in Nantucket, a small island off the coast of Massachusetts, on a whaling ship. It quickly becomes clear that Captain Ahab has no intention of going on a regular whaling voyage but is planning a campaign of revenge against the notorious whale Moby-Dick, who cost him a leg in an earlier encounter.

I had braced for a thrilling adventure novel, breakneck and suspenseful from first to last page—as many classics marketed as adventure novels are. However, the book doesn’t fit neatly into that category. Melville’s style is expansive and slow, and so the story begins with Ishmael’s crossing from New Bedford to Nantucket, a stopover in a small harbor inn, and the search for a suitable ship to join. Melville does a superb job conjuring a genuinely maritime atmosphere, describing places, people, and the whole milieu with such loving detail that you can vividly picture the dark dives, the Pequod (the whaler) rigged to the nines for whaling, and of course the sea.

“[…] how the wind howled and the sea surged and the ship groaned and pitched, yet still hurled its red hell farther and farther into the blackness of sea and night, and defiantly bit down on the whitish bone in its maw, and angrily spat spray to all sides, freighted with savages, loaded with fire, with a burning corpse aboard on its way into the blackest darkness—thus the Pequod stormed along like the material image of the soul of its possessed leader.” (p. 656)

The book’s title also includes “The Whale,” and that’s apt, because the whale in general—not just Moby-Dick—stands at the center. This book immerses you in the world of nineteenth-century whaling, which feels very archaic today. In small rowboats they set after the great marine mammals, with a strong seaman in the bow who harpooned the poor creatures and lanced them until they finally died. Then the whales were flensed, i.e., the blubber layer was stripped off. This layer protects the whale from the cold of the sea and contains the valuable oil (train oil), which in those days—before petroleum took over—was used as fuel.

The reader learns all these things, and while the whaler Pequod with Captain Ahab stands at the center, the narrative is repeatedly interrupted by extensive descriptions of whaling, its culture, everyday life, customs, dangers, and of course the whale itself. In meticulous detail, Melville explains how things were done, how the ships were built, the significance of spermaceti, how the killing and flensing of the whale proceeds in detail, and how the sailors thought and behaved. Melville even provides an overview of whale species, argues—true to his time—the case for whaling and its importance, and goes deeply into detail, even describing the hours spent on lookout in the mast-head. As a result, the ship doesn’t sail until page 200, and even then the pace remains unhurried and is repeatedly interrupted for these thorough explanations.

I’m torn about the book’s style and structure. On the one hand, I find it fascinating to learn about that era and life at sea. For all the dangers and hardships the sailors had to endure, it has something romantic about it: an apparently unfathomable sea, an undiscovered world full of adventure. On the other hand, I never quite found a reading flow, because the current events on board are repeatedly set aside for explanatory passages in an objective tone. Ishmael certainly tells his tale vividly and presents the facts in colorful fashion, garnished with many elaborate mythological, theological, and scientific comparisons and digressions. But if you set the general explanations about the whale against the on-board adventures, roughly three quarters of the book consist of detailed expositions on whales and whaling, and a quarter of the actual story. That leads to pronounced stretches and greatly diminishes the entertainment value—especially because Melville really goes into the minutiae, dissecting the whale’s anatomy down to the skeleton, from head to tail flukes. The entire process—from the hunt to cleaning the ship after the oil has been rendered and stored—is laid out across many short chapters, so the pace of the actual story is reduced to an absolute minimum. I found that a pity, because the episodes at sea when the Pequod goes after whales, as well as the brief reports from other ships, are genuinely exciting and exactly the sort of thing I had expected.

The question is how to blend factual descriptions of whaling with an entertaining narrative arc so that a book remains a pleasure to read—and there are some good examples. Captains Courageous by Kipling is one such book that interweaves depictions of life in the fishing trade with a gripping story, delivering both solid entertainment and facts. Another example is Arthur Conan Doyle’s Dangerous Work: Diary of an Arctic Adventure, where he presents the experiences and observations from his voyage on a whaler in an engaging way. Perhaps that’s just my perspective, because I’ve read a lot in this vein. It’s clear that Melville wanted to present a complete picture of the whale and whaling and leave nothing out. In that sense, comparing it with the two books above isn’t entirely fair. Moreover, his reflections on whales and whaling certainly contain a great deal of substance, demonstrating his wide reading and his impressive ability to synthesize it—far beyond the scope of the books mentioned.

The book wants to be both: a natural history of whales and an adventure about whaling. Moby-Dick is meant to be a concrete instance of the extensively described species of whale, but in connection with the adventure it also says something on a meta-level. The numerous references to biblical passages, Christian stories, mythology, and works of world literature—above all the story of Jonah, swallowed by a whale and spat out chastened—lend the book a philosophical, metaphysical dimension. Shakespeare’s figures also inspired Melville, so Hamlet, Timon, Lear, and Iago recur. According to the afterword, echoes of 160 texts can be heard in this work, alluded to by Melville in one way or another. Scholarly works and reports of his time also served as sources for the scientific view of the whale and whaling.

His skepticism toward Spinoza’s pantheism, but also the virtuous piety and fear of God portrayed, are clear indications that the book, in this respect, breaks a lance for Christian theism and is thus also an allegory of faith. In places this becomes quite plain.

“But if even the great sun does not move of itself but runs through the heavens as an errand boy; if not a single star can turn without an invisible power—how then can this one little heart beat, this one little brain harbor thoughts, unless God drives this heartbeat, thinks these thoughts, lives this life, and not I.” (p. 823)

In many passages he offers striking ideas that genuinely captivated me.

“[…] and if we go further and consider that the mysterious cosmetic which produces all their color—the great principle of light—remains forever white and colorless itself and, if it acted on matter without a medium, would overlay everything—even tulips and roses—with its own empty pallor; if we consider all that, the gout-ridden universe lies before us like a leper, and like a willful traveler in Lapland who refuses to wear tinted, color-giving glasses, so the wretched unbeliever stares himself blind, unable to turn his gaze from the endless white shroud that veils everything he sees around him.” (pp. 322–323)

For me, then, it’s a book that feels somehow inconstant, hard to grasp as a whole. Editor Daniel Göske calls Moby-Dick a draft in the afterword—an outline. From my point of view, a draft that is somehow complete and at the same time entirely open.

The fusion of narrative, concrete, and abstract—even metaphysical—elements, with a sidelong glance at texts from world literature, is also, in my view, why this book is counted among world literature. The question, however, is whether an allegorical meaning was actually planned from the outset by Melville and consciously inscribed into the work. The afterword asserts that it wasn’t (cf. p. 886), but sees as a central element of this engagement “an existential struggle for the truth behind a deceptive, elusive world of appearances” (p. 896). I’d agree with the afterword here, for the work seems to me too uncontrolled, too diffuse to reveal a clear set of intentions beyond the story being told. The sea and whaling were, given Melville’s career as a sailor, an inherent frame, and a story with that background, artfully elaborated, inevitably leads to humanity’s big questions.

A central theme is the struggle between humankind and nature, between good and evil, between God and the Devil. To forge a connection between mythology, faith, and the whale—to give weight to the image of the Leviathan from the outset—the book begins with excerpts about whales from various ancient sources. But of course this struggle is embodied most vividly in Captain Ahab’s vendetta against the white whale Moby-Dick. It quickly becomes clear that Ahab is also a symbol. He unites many roles, even if his course of action doesn’t surprise. Fearless, he confronts nature and defies it, behaves like a devil, reckless toward himself and others, and at the same time he isn’t completely blinded but sees quite clearly. He embodies the dictator, the autocrat, the demagogue. Moby-Dick, as representative of pitiless nature, also unites several facets—from God’s vengeance, as in the biblical Jonah, to mute, instinct-driven nature—and that frees the book from any form of stereotype, which I liked very much. As a reader you can interpret and discover a great deal here.

What’s particularly impressive is the multi-layeredness of Melville’s text. From ordinary narrative to sermons, prophetic speeches, natural-historical descriptions, monologues, staged dialogues, and even a chorus-like multitude of voices before the mast—everything is on offer here. Together with the many cross-references and the interruptions by comparatively objective treatments of whales and whaling, the result is a diffuse work, and at the same time the reading flow is heavily disrupted—both linguistically and structurally. That’s also reflected in the multitude of chapters, often quite short. The reader can’t really develop a sense of closeness to any character, especially not to the narrator Ishmael, who increasingly recedes into the background as the novel progresses. I sorely missed that focus and the absence of a clearly guided narrative structure. I read the book with my intellect and never with feeling or emotion. The hunt for the whale filled me with suspense, but any outcome would have left me cold. The highest art is to abduct the reader body and soul, and Melville didn’t manage that for me.

The Hanser edition, however, did win me over again—both for its high-quality production and for the extensive supplementary material and, of course, the translation. You can immediately sense the care and dedication invested in the text, and a glance at the editorial note confirms the effort involved. Linguistically, the book is very pleasant to read, while aiming to echo the language of the period.

“[…] but the special patina of the English original should be emulated. That also applies to the older stylistic forms inscribed in the novel, insofar as usable German equivalents exist for them.” (p. 907).

The translator Matthias Jendis uses nautical terms that were new to me. Very often you read fieren/abfieren, meaning to haul down, lower, let down. Or belegen, which refers to securing and making fast lines or ropes. The book includes a glossary of all nautical terms, which I consulted repeatedly and found very helpful.

The afterword also gives a good overview of the work’s genesis and history. In the summer of 1851, under pressure from the publishers, an initial New York edition appeared that was full of errors and contradictions; Melville apparently didn’t have enough time to correct them. The September 1851 London edition was likewise riddled with errors. The November 1851 New York printing finally included numerous corrections. The October 1851 London edition, by contrast, had no epilogue and was trimmed of some delicate passages to suit female readers. The early reviews in the USA were accordingly rather negative, whereas some British reviewers praised his powers of observation, verbal force, and imagination. As mentioned above, the book only became famous in the 1920s and has since been adapted countless times into various formats—youth editions, radio plays, films—and, of course, translated many times.

There’s also a timeline of Melville’s life appended, which at points reads quite adventurously. Melville’s father was a businessman who ultimately went bankrupt. Melville never really achieved financial or professional security and took on many jobs in many places. He himself signed on a Nantucket whaler and gained experience before the mast, which he eventually processed literarily—not only in Moby-Dick. He was widely read and moved in New York’s literary circles, writing articles and reviews for newspapers. As a writer, however, he never truly gained a foothold, and when he died in 1891 he was all but forgotten in the USA.

Conclusion: Moby-Dick leaves me with mixed feelings. On the one hand, you can only respect the work’s richness—both linguistically and in terms of content. Whether ordinary narration, sermon, prophetic speech, natural-historical description, monologue, artful dialogue, or a chorus presented in the style of an operetta, this work offers astonishing variety. In terms of its broad range of interpretive possibilities, its numerous metaphysical readings, and its exciting episodes on the high seas, it’s a success. On the other hand, I never quite found a reading flow, as the action is repeatedly interrupted and Ishmael, the narrator, lays out, in a lively yet still matter-of-fact style, every detail about whales and whaling at great length. The shifting modes of narration reinforce this impression and, for me, impeded immersion in the melody of his otherwise very beautiful prose. In fact, in several places in this edition I was grateful for the very sensible, carefully chosen cuts the editor made. Nor does the reader develop real closeness to the characters, so I didn’t fully immerse myself in the work but read it more with my head than my heart. In a classic of world literature, I would have preferred a more balanced ratio. So I can offer a clear recommendation mainly to readers who feel a bond with the sea, are fascinated by the Leviathan, or appreciate many literary, theological, and mythological side glances.

Book information: Moby-Dick; or, The Whale • Herman Melville • Carl Hanser Verlag • 1,048 pages • ISBN 9783446200791

Lieber Tobi,

ein schöner Text über Moby Dick in der Übersetzung von Jendis, danke.

Gestatte mir, Dir und Deinen Lesern einen Beitrag von mir nahezulegen,

in dem ich die Jendis-Übersetzung mit der von Friedhelm Rathjen abgleiche.

(Beide sind eng und (beinahe dramatisch) verknüpft.

http://lustauflesen.de/moby-dick-zwei-ubersetzungen/

Falls Dir diese Werbung an dieser Stelle zu penetrant erschein, lösche sie.

lg_jochen

Lieber Jochen,

vielen Dank für deine Worte und deinen Hinweis auf deinen Beitrag. Den lese ich mir natürlich nachher gleich durch, weil so ein Blick auf unterschiedliche Übersetzungen finde ich immer ganz interessant! Die Werbung kann hier gerne bleiben und passt sehr gut!

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Ich habe schon mehrfach gelesen dass das Buch etwas sperrig sein soll und auch deine Rezension scheint das zu bestätigen. Nichtsdestotrotz eine sehr schöne Ausgabe, typisch Hanser eben.

Die Bücher vom Hanser-Verlag sind einfach klasse, aber da hab ich ja schon einige Male darüber geschrieben. Hast du das Buch auf deinem SuB/Wunschliste?

Nein, aber andere Bücher von Hanser und Mare. In der kommenden Woche fahre ich endlich mal in ein Antiquariat in Bamberg und hoffe dort ein paar Schätze zu finden.

Zum Thema “Beuteschema” fiel mir gerade ein Buch ein: B.Traven, “Das Totenschiff”.

Vielen Dank für den Lesetipp. Gleich mal auf die Wunschliste gesetzt, der Klappentext liest sich ganz gut!

Das wurde mal im Rolling Stone groß besprochen. Um den Autor scheinen sich ja viele Mythen und Gerüchte zu ranken, seine Identität ist ja offenbar nicht zweifelsfrei geklärt.

Hallo Tobi!

Vielen, vielen Dank für deine Eindrücke. Ich möchte mich “Moby Dick” in diesem Jahr ja auch endlich widmen – und trotz deiner kritischen Anmerkungen hast du es geschafft, mich noch neugieriger auf das Buch zu machen. Mir ist damals bei meiner ersten näheren Beschäftigung mit “Moby Dick” bereits aufgefallen, dass die Meinungen stark auseinandergehen und es viel Kritik an der Umsetzung gab/gibt. Doch gerade die kritisierten Punkte sind es, die damals mein Interesse am Buch richtig geweckt haben. Ich bin gespannt, ob mich “Moby Dick” so begeistern wird, wie ich denke, oder ob ich das Buch am Ende doch so ernüchtert zuklappe wie du.

Liebe Grüße

Kathrin

Liebe Kathrin,

da bin ich gespannt und du musst unbedingt darüber bloggen. In dem Buch steckt eine Menge und kann durchaus nachvollziehen, dass es einige begeistert. Je nachdem, was man darin sucht oder was einen aktuell reizt, das ist ja durchaus auch abhängig von der aktuellen Stimmung und Ausrichtung die man hat.

Liest du das Buch im englischen Original, oder hast du schon eine übersetzte Ausgabe daheim?

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Hallo Tobi,

da stimm ich dir zu: Ich denke, wie man “Moby Dick” (oder auch andere Klassiker gerade des 19. Jahrhunderts) aufnimmt, hängt stark auch davon ab, aus welchen Gründen man es liest und was man sich davon erwartet. Wer z.B. “Les Miserables”/”Die Elenden” nur wegen der Tragik der geschilderten Leben lesen möchte, wird wohl enttäuscht. Wer bei “Moby Dick” nur temporeiche Action erwartet, dem geht es genauso. Mich hatte nur ein wenig überrascht, dass gerade du, der die Vielschichtigkeit der Bücher aus dem 19. Jahrhundert so schätzt, “Moby Dick” ohne große Begeisterung beendet hat. Deine Kritikpunkte an sich kann ich aber durchaus verstehen.

Ich werde “Moby Dick” auf Englisch lesen. Ich hatte keine Lust, wieder erst monatelang herauszufinden, welche Übersetzung wohl am wenigstens gekürzt und gleichzeitig gut lesbar ist. Und während meiner Suche kündigte Calla Editions eine leinengebundene, illustrierte Ausgabe an – da konnte ich einfach nicht widerstehen. Allerdings hoffe ich, dass ich auch alles gut verstehe – wenn es schon in der deutschen Übersetzung Begriffe gibt, die weniger gebräuchlich sind bzw. zum Teil auch Seemannsjargon sind, wird das Lesen auf Englisch garantiert nicht allzu einfach ;) Aber ich werde auf jeden Fall berichten!

Liebe Grüße

Kathrin

Hallo Tobi,

das war eine sehr spannende und ausführliche Rezension.

Ich selbst habe “Moby Dick” gelesen, als ich ca. 12 war. Im Nachhinein frage ich mich wirklich, wie ich damals auf diese Idee gekommen bin und wer in unserer Stadtbibliothek das Buch in der Jugendabteilung stehen lassen hat. Auf jeden Fall blieb mir vor allem die Geschichte und die detaillierte Beschreibung der Sezierung etwas abschreckend in Erinnerung. Ich weiß noch, dass ich grundsätzlich auf der Seite des Wals war. Die weitschweifenden Ausführungen, von denen du berichtet hast, habe ich auch noch als störend im Kopf, allerdings habe ich mir damals nicht halb so viele Gedanken über ihre Bedeutung gemacht, wie du. Das Buch sitzt seit dem verschwommen und in meinem Kopf und löst immer gemischte Gefühle bei mir aus. Daher lese ich sehr gerne Rezensionen darüber, um mir selbst klar zu werden, was mich damals wohl so sehr daran gestört haben kann. Nach deiner Rezension, bin ich da schon einige Schritte weiter. Vielen Dank dafür!

Viele liebe Grüße

Ciri

Liebe Ciri,

ich bin mir sicher, wenn mir das Buch viel früher in die Hände gefallen wäre, bevor ich schon so viel über das Meer und die Seefahrerei gelesen habe, dann hätte ich gewiss einen anderen Blick auf das Buch gehabt. Das ist immer auch eine Frage, welche Erwartungen man hat. Seine Beschreibungen haben schon was für sich, da erfährt man schon eine Menge und mit den Vergleichen und den vielen Seitenblicken ist das schon eine Leistung.

Ich kann deine unentschlossenen Gefühle durchaus nachvollziehen, denn das ist genau das Empfinden, was ich meine, wenn mir das Buch irgendwie wie ein “vollständiger Entwurf” erscheint.

Liebe Grüße und vielen Dank für deinen Kommentar!!

Tobi

Vielen Dank für die ausführliche und umfassende Besprechung! Ich selbst habe “Moby Dick” während meines Studiums im englischen Original gelesen, was vermutlich noch einmal zur Intensivierung der Atmosphäre beigetragen hat. Eine deutsche Ausgabe würde ich bei Gelegenheit aber auch gerne einmal lesen. Vielleicht wird es dann auch die von Hanser.

Ich kann mich an keine Störungen meines Leseflusses durch allzu detaillierte Beschreibungen erinnern, es sei denn, ich musste in diesem Zusammenhang englische Vokabeln nachschlagen, die mir nicht geläufig waren… Das Buch “Moby Dick” gehört jedenfalls zu meinen persönlichen Favoriten, wie ich auch Herman Melville nach wie vor für einen unterschätzten Autor halte. Aber “Einen Klassiker, den kaum jemand kennt” – das ist doch sicherlich und hoffentlich ironisch von Dir gemeint, oder?! Ich kenne jedenfalls kaum jemanden, der “Moby Dick” nicht kennt. Es haben natürlich nur wenige das Buch gelesen; aber kennen dürften es doch die meisten…

Beste Grüße,

A. Goldberg

Lieber Anton,

also im englischen Original ist das wahrscheinlich nochmal ein ganz anderes Erlebnis. Allerdings lesen sich die Übersetzungen vom Hanser Verlag schon sehr gut, da kann man wirklich nicht meckern.

Ich habe Moby Dick nicht als eine Geschichte empfunden, die mich so richtig gepackt hat und in die ich komplett eingetaucht bin, weil sie mich so mitgerissen hat. Wieso beschreibe ich ja in meiner Rezension. Aber hier sind die Geschmäcker und auch die Vorstellung von einer Erzählung durchaus unterschiedlich. In “Horcynus Orca” habe ich diesen sehr mitreißenden Lesefluss sehr stark empfunden, auch wenn das Buch auch die üblichen Spannungsbögen völlig verzichtet und noch wesentlich langsamer als Moby Dick ist. Einfach weil mich die Sprache da gepackt und die wunderbare Darstellung des Meeres so in das Buch gesaugt hat.

Moby Dick ist alles andere ein Geheimtipp. Meine Einleitung spielt darauf an, dass dieses Buch zu Lebzeiten von Melville völlig unbekannt war und erst in den 1920er Jahren wiederentdeckt wurde. Ich glaube Moby Dick kennt wirklich jeder, auch wenn es vielleicht nur ein kleiner Teil gelesen hat. Alleine schon wegen den vielen Filmadaptionen.

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Ich sehe das wie Anton Goldberg : Moby Dick kennt wirklich jeder! Ich lese es auch gerade :)

Liebe Tinka,

natürlich ist Moby Dick kein Geheimtipp, das Buch kennt wirklich jeder, sogar die, die nicht viel Lesen. Es gibt ja ungefähr 1000 Verfilmungen von dem Buch. In meiner Einleitung schreibe ich ja, dass meine Rezension so beginnen würde, wenn es in den 20er Jahren des vergangenen Jahrhunderts nicht von einigen Literaturwissenschaftler neu entdeckt worden wäre.

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Lieber Tobi,

danke für die Vorstellung dieses Klassikers….und ich muss gestehen, es noch nicht gelesen zu haben, ob wohl ich die viel knappere Jugendausgabe im Regal stehen habe. Das wäre doch wenigstens ein Anfang ;-)

Viele Grüße,

Heike

Liebe Heike,

ich kann mir gut vorstellen, dass bei der Jugendausgabe die Ausführungen über den Wal und Walfang gestrichen wurden. Und dann bleibt eine ziemlich spannende Geschichte. Für den Anfang könnte es also nicht besser sein ;)

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Lieber Tobi,

Ich bin schockiert! 1048 Seiten hat das Buch (die reine Erzählung um die 800)? Ich wusste nicht, dass das Buch im Original so umfangreich ist und dachte, ich hätte mit meiner Edition aus dem Anaconda Verlag schon die ungekürzte Version gelesen. Wie ärgerlich!

„Moby Dick” hat mir beim Lesen ganz gut gefallen, hat mich aber nicht nachhaltig beeindruckt. Ich bin mit der Seemannssprache nunmal nicht wirklich vertraut und jedesmal zu googeln hätte mir die Freude genommen. Ich kann dein Fazit also gut verstehen.

Seemannsgeschichten magst du aber? Und Jack London auch? Vielleicht sagen dir ja seine Geschichten rund um den Abenteurer David Grief zu: “Ein Sohn der Sonne und andere Südseegeschichten” ;)

Liebe Jenny,

320 Seiten ist schon krass gekürzt. Aber das würde ungefähr hinkommen, wenn man alle allgemeinen Ausführungen über den Wal und Walfang weg lässt. Meine Ausgabe hatte ja ein sehr gutes Glossar mit den Begriffen aus der Seefahrerei. Aber ich muss gestehen, einen Teil kenn ich schon ganz gut, aber manche vergisst man dann einfach recht schnell wieder. Die Büchergilde-Ausgabe von “Über Bord” von Kipling hat eine sehr schöne Skizze, die alle Teile eines Schiffs benennt. Zusammen mit dem Glossar bekommt man da ein recht guten Überblick.

Von einem Buch von Jack London gibts bald eine Rezension hier. Aber von ihm hab ich noch einiges auf meiner Wunschliste.

Btw: Ich wollte schon ein paar Mal bei deinem Blog kommentieren, aber da kann man leider nicht anonym (d.h. mit Name/URL) schreiben.

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Lieber Tobi,

so ein Glossar scheint wirklich hilfreich zu sein und hätte mir auch sehr geholfen. Wobei: eine Zeichnung wie bei Kipling hätte mir wohl noch mehr geholfen. Aber gut, auch so bin ich beim Lesen noch gut mitgekommen. Anscheinend „muss” ich „Moby Dick” nochmal lesen – kann es sich ja gleich hinter „Les Miserables” anstellen.

Ouh, danke für den Hinweis! Ich habe das mit den Kommentareinstellungen direkt geändert. So ist das, wenn man aus Unwissenheit einfach alle Standardeinstellungen beibehält. Da bin ich immer sehr dankbar, wenn mich jemand darauf aufmerksam macht.

Liebe Grüße

Jenny

Ave,

eine wirklich gewaltige Rezension, die mir aber trotz aller “Abschweifungs-Kritik” nur noch mehr Lust auf das Buch gemacht hat. Ich glaube, ich werde mich trotz allem an die Langfassung wagen – es gibt ja auch eine gekürzte Übersetzung, die eben diese Sperrigkeit durch die vielen Fakten etwas aufhebt. Allerdings bin ich mir nun nicht mehr ganz so sicher, ob ich mich, wie ursprünglich geplant, tatsächlich an der englischen Version versuchen soll oder die Geschichte nicht doch lieber durch die Muttersprache etwas vereinfachen soll.

Mit freundlichen Grüßen,

Seitenfetzer

Lieber Seitenfetzer,

komplett durchgefallen ist das Buch bei mir ganz sicher nicht. Melville legt hier schon was gewaltiges vor und ich glaube nicht, dass du es bereuen wirst, das Buch zur Hand genommen zu haben. Die Übersetzung vom Hanser Verlag ist schon ziemlich gut. Aber im Original ist das wahrscheinlich nochmal was anderes. Ich bin auf jeden Fall gespannt, was du dazu sagst. Also vergiss nicht darüber zu bloggen ;)

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Hallo Tobi,

daß man sich mit Moby Dick keine einfache Lektüre ins Haus holt, sollte einem bewußt sein. Herman Melville war mit dem konzipierten Text seiner Zeit weit voraus. Der Schriftsteller stellt gewiß einige Ansprüche an seinen Leser, die über die reinen Beschreibungen der Jagd auf den weißen Wal und einem Segeltörn über die sieben Meere weit hinausgehen. Melville erwartet so unter anderem von seinem Leser Kenntnisse biblischer und mythologischer Bezüge sowie diverser Klassiker des angelsächsischen Raumes.

Vollkommen neu und selbst für heutige Leser ungewohnt ist die Montagetechnik des Romans mit seinen vielen Versatzstücken. So gibt es die Arbeitsbeschreibungen der Jagd auf See, zahlreiche mythologische Anspielungen und vieles andere mehr. Auch die psychischen Reflektionen sind damals wie heute keine Lektüre, die es dem Leser leicht macht. Es liegt hier kein Roman zugrunde, der einen kontinuierlichen Handlungsstrang mit einem festen dramaturgischem Höhepunkt besitzt, sondern dem Leser Gedankensprünge, Assoziationen, Überlegungen etc. vorstellt, diese regelrecht abringt und somit hautnah erlebbar macht.

Solche literarischen Montagetechniken wie beispielsweise den Alltag an Bord eines Walfängers zu Anfang des 19. Jahrhunderts, die polyglott zusammengewürfelten Charaktere, die auf dem Schiff segeln, die Berufssprache der Seeleute und Fischer, eingehende Selbstreflektionen, ökonomische und philosophische Aspekte etc. findet man erst wesentlich später in den Romanen von John Dos Passos („Manhattan Transfer“) oder aber Alfred Döblin („Berlin-Alexanderplatz“).

Wer sich durch Melvilles Roman geduldig und neugierig gearbeitet, nein, gelesen hat, der kann wirklich ein außergewöhnliches Stück Literatur sein eigen nennen.

Hallo Tobi,

Danke für diese ausserordentlich interessante Rezension. Moby Dick ist auf jeden Fall eines meiner Lieblingsbücher. Von dieser Übersetzung im Hanser Verlag habe ich vorher noch nichts gehört, ich bedanke mich, denn die 300 Seiten Version war die einzige deutsche Ausgabe, die ich gefunden habe.

Hallo Tobi,

ja, diese enzyklopädischen Einschübe im Text sind schon manchmal störend. Aber ich finde, die gehören zum Buch einfach dazu – ohne sie und ohne die Ironie im Erzählton könnte das Ganze leicht ins christliche Lehrstück abkippen.

Was ich getan habe und keinem raten kann: Den ganzen Schmöker (ungekürzt) und auf Englisch zu lesen. Man versteht zwar genug, aber nicht alles, und ich bin mir sehr sicher, dass man da bei Moby Dick was verpasst.

Weil ich tatsächlich keine ungekürzte Ausgabe zum erschwinglichen Preis bei thalia gefunden habe, stammt die deutsche Ausgabe auf meinem SuB aus dem Antiquariat.

Was ich dir aber unbedingt noch empfehlen möchte, ist ein anderes Werk von Melville: Bartleby, der Schreiber. 74 Seiten kurz ist die deutsche Übersetzung (insel taschenbuch) und erzählt in herrlicher Sprache von einem Menschen, der sich dem blinden Erfolgseifer der Arbeitswelt entzieht. Ich kanns keinem verdenken, wenn er den dicken Wal nicht liest, aber Bartleby ist knackig kurz und einfach cool.

Liebe Katrin,

dass das Buch Englisch echt schwer zu lesen ist glaube ich sofort. Schon alleine wegen den verschiedenen Stilrichtungen, die Melville darin anschlägt. Bartleby ist ein Tipp, der kommt auf meine Liste. Ob Melville auch knackig und kurz kann muss ich natürlich wissen ;)

Liebe Grüße

Tobi