Julie or The New Heloise • Jean-Jacques Rousseau

I often find excellent book recommendations within books themselves. When an author or a title keeps being mentioned, it certainly catches my attention. One such book is Julie, or the New Heloise by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, which was recently mentioned in a work by Balzac and has crossed my path countless times. The premise also sounds quite appealing: an epistolary novel about an unmarried young woman who gives in to an improper love affair. A book scandalous enough to become a topic of conversation in Parisian salons. And coming from a French author, of course. Naturally, my curiosity was piqued, and I couldn’t resist for long.

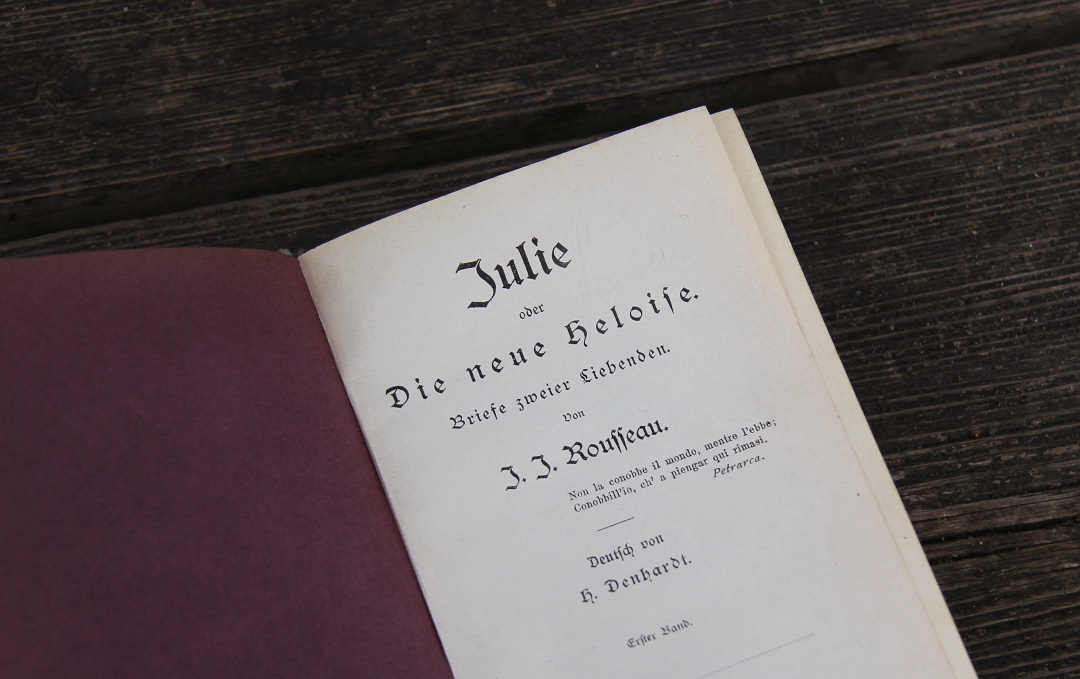

Of course, I immediately went looking for a handsome collector’s edition — only to be sorely disappointed. An eBook is easy enough to find, but otherwise the situation looks bleak. There are a few shabby paperback editions that are quite expensive, as well as some much older (and even pricier) antiquarian hardcovers. I eventually found a pretty good deal on eBay and managed to snag both volumes in a compact format for just a few euros. They were published by Philipp Reclam jun. There’s no year printed, but from my research I suspect the edition dates from around 1900. The books are quite worn, printed in Fraktur type, and the spine of the first volume cracked as I was reading (the second one was already broken). So, not exactly a bibliophile’s dream, but there’s something charming about holding such old books in your hands.

The story can be summarized quite easily: the beautiful Julie, from an aristocratic family, falls in love with her tutor, a young man of common birth, and begins an affair with him. In the 18th century, this was, of course, socially and morally unacceptable, and thus begins a struggle for true virtue. The book is written as an epistolary novel, consisting of correspondence exchanged between the lovers and people in their circle — for instance, Julie’s cousin. There are also some letters between secondary characters. The format works very well, allowing readers to follow the progression of the story, the encounters, and their outcomes in detail. Because the characters tell and describe events from their own perspectives, one feels a pleasant closeness to them.

Julie, or the New Heloise was published in 1761, and my edition is from around 1900 — so it’s clear that one encounters a very different kind of language than in a contemporary book or a newly translated classic. The style is verbose, emotional, flowery, and old-fashioned. But that fits perfectly with the story, the time, and the theme. I love writing that brims with passion and fervor — and the French, true to form, go all in. In love, as in all things, it’s always all or nothing: eternal love or death, perfect virtue or vice. The book overflows with emotion. What exploding cars are to Alarm für Cobra 11, bursting passions are to French authors — and here, lovers explode just as reliably as those cars on TV. The characters regularly throw themselves at each other’s feet, drenching them with tears. I thoroughly enjoyed it all. This is grand drama — and exactly my style.

“Do you realize to what degree a lover who lives only for you can infuse joy into your existence? Do you comprehend in its full extent that henceforth I shall live, act, think, and feel only for you? No, you precious source of my being, I shall have no soul but yours; I shall be nothing more than a part of your self, and in the depths of my heart you will find so sweet a life that you will not feel what charm your own has lost.” (Volume 1, p. 452)

The novel consists of two volumes. I found the first volume very entertaining in terms of story. There are, of course, some passages where Saint-Preux, Julie’s lover, goes on at great length about Parisian society (and there are other lengthy letters as well), but overall, it offers a gripping narrative. I could easily empathize with the protagonists, and even though it’s quite sentimental, it’s a touching love story. What can I say — I have a sensitive heart and am easily moved by the fate of two lovers. That said, there are moments when Saint-Preux comes across as a bit of a wimp — overly emotional or unstable. Realistic it is not, let’s be honest.

Between the first and second volume there’s a time jump of about eight years. My curiosity to see how things would continue was still strong — but the pace slows down drastically. The first half of the second volume is quite tedious. Here Rousseau goes into great detail describing how an idyllic agricultural estate functions perfectly, touching on many details. It’s almost philosophical, as his goal is to show how the virtuous country dweller should live, regardless of class. In many ways this struck me as surprisingly progressive — it even reminded me a bit of modern startup culture. At the same time, his views on women and child-rearing are utterly antiquated and regressive, enough to send chills down one’s spine. In total, he touches on a wide range of subjects — faith, morality, education, the right to suicide, atheism, and society — some in more detail than others.

Only the second half of the second volume becomes engaging again, as the story of the protagonists resumes. The ending, however, felt contrived and failed to captivate me. The pacing becomes slow again, and although Rousseau tries to tie things together through the theme of faith, I couldn’t quite connect with his conclusions.

What makes the letters somewhat more believable — albeit lengthy — is that the two lovers keep rehashing the same topics. Virtue, vice, and every statement they make are dissected and analyzed by the other in painstaking detail. This leads to many long letters that add little new. Rousseau is quite aware of this, and in a footnote (see Vol. 2, p. 321), he plainly states that he doesn’t care. A bold declaration, to say the least. Still, these contradictions and the misguided reasoning of the letter writers make the collection feel authentic.

In an extensive preface, Rousseau explains what he aims to achieve with this work. Partly in dialogue with his publisher, he outlines how the first book represents vice and the second, a virtuous way of life. He seeks to flatter his rural readership, painting life in the countryside as idyllic and morally superior to the depravity of the big city — hence his famous slogan “Back to Nature.” In the second volume, he elaborates on this at great length, though not particularly effectively in my opinion. One can imagine such a rural utopia, but he fantasizes about a society that could never really exist — after all, he’s talking about human coexistence. Reality looks quite different, and so much of what he describes in the second volume felt overly theoretical. Combined with the long-winded descriptions, I often found myself bored.

Through this story, Rousseau clearly criticizes class distinctions and makes a case for marriage based on love. However, in the second volume he revises much of this and instead emphasizes religiosity, virtue, honesty, and moderation as the ideal way of life — or at least that’s how I read it. In many respects, especially in his vision of a modestly managed vineyard and its guiding principles, I found Rousseau surprisingly forward-thinking. Yet his portrayal of religion as a means to compensate for lack of freedom and suppressed emotion, and his insistence that a virtuous life should take precedence over personal happiness, come through quite clearly. The characters all remain confined within their societal roles, rebel only slightly, and ultimately conform to the moral expectations of their time. The ending, in particular, highlights the importance of religion to each character. In both the preface and the footnotes, Rousseau distances himself from his characters, describing their philosophy as provincial and limited. I find it difficult to interpret Rousseau’s worldview or to say what message he truly wished to convey with this book. Perhaps a good reason to soon turn to his Confessions.

Julie, or the New Heloise was one of the greatest bestsellers of the 18th century, published more than 70 times and frequently sold out. Originally, the book was titled Letters of Two Lovers from a Small Town at the Foot of the Alps, as the story is set in the Swiss Alps. The title Julie, or the New Heloise refers to the medieval love story of Heloise and Peter Abelard. That 12th-century tale begins similarly: Heloise falls in love with her tutor Abelard, enters into an affair with him, which is later discovered — leading to tragedy and turmoil.

Julie, or the New Heloise also reminded me of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. It’s also an epistolary novel, written in a similar style, and deeply intertwined with nature. Rousseau constantly describes the natural world, linking it to his characters and their emotions. Considering Goethe’s novel appeared thirteen years after Rousseau’s and the strong similarities between them, I wouldn’t be surprised if Goethe had drawn inspiration from Rousseau’s work.

Rousseau is certainly one of the biggest names in the pond. As one of the most important philosophers of the Enlightenment, his work is deeply tied to the French Revolution. His pedagogical call of “Back to Nature” is clearly reflected in this novel as well. Those who wish to learn more about Rousseau and his philosophy will find that reading this book alone isn’t enough — one likely has to turn to his Confessions. Whether that’s truly the case, I’ll find out soon — and report back.

Conclusion: I was very curious about this book — both because of its many mentions in 19th-century literature and because of its blurb (or rather, the summaries one finds). The first volume captivated me with its heartfelt scenes, beautiful old-fashioned romantic language, and love story. The first — and especially the second — volume, however, often felt too talkative, too detailed, and lost much of its narrative tension. Rousseau’s digressions on various topics — from the ideal management of a farm to education, faith, and morality — struck me as mixed, sometimes insightful but often tedious. Overall, it’s a lovely love story that’s at times gripping, at others contrived. Certainly not a must-read, but one you won’t regret picking up.

Book Information: Julie, or the New Heloise • Jean-Jacques Rousseau • Reclam • 533 pages (Vol. 1) and 495 pages (Vol. 2)

und so liebevoll und ausführlich hast. Briefromane sind also keine Erfindung vom Autor von Daniel Glattauer *Gut gegen Nordwind*. Ich habe grad ein Buch von der südfranzösischen Autorin Thyde Monnier *Der unfruchtbare Feigenbaum* wieder gefunden, deren Werke ich vor Jahrzehnten verschlungen habe ;-). Ich denke sie wird gar nicht mehr verlegt… werde ich mal googeln …

Ein schönes langes WE für Dich!

Angela

Liebe Angela,

oh schade, da ist nur ein Teil von deinem Kommentar angekommen. Der beste Briefroman, den ich bisher gelesen habe, ist “Gefährliche Liebschaften” von Choderlos de Laclos. Das ist ein richtig gutes Buch. Aber viele Briefromane habe ich nicht im Schrank stehen. Die Richtung kommt doch zu selten vor und ist glaub ich schon sehr schwierig umzusetzen. Weder Glattauer, noch Monnier kenne ich. Das scheinen ziemliche Geheimtipps zu sein.

Liebe Grüße und auch dir ein schönes langes Wochenende

Tobi

Merkwürdig, mein Lob für Deine Rezi wurde verschlungen,,,Sorry!