The Ambassadors • Henry James

Until now, I only knew Henry James by Washington Square, although I hadn’t read that or any of his other books. When this handsome, newly translated edition appeared from Hanser, I couldn’t resist and simply had to have it. The content sounded very tempting as well, since I love society novels, and this struck me as a pure example of the genre. Plus, after my rather extensive excursions into the world of French literature, I finally wanted to read something by American or English authors.

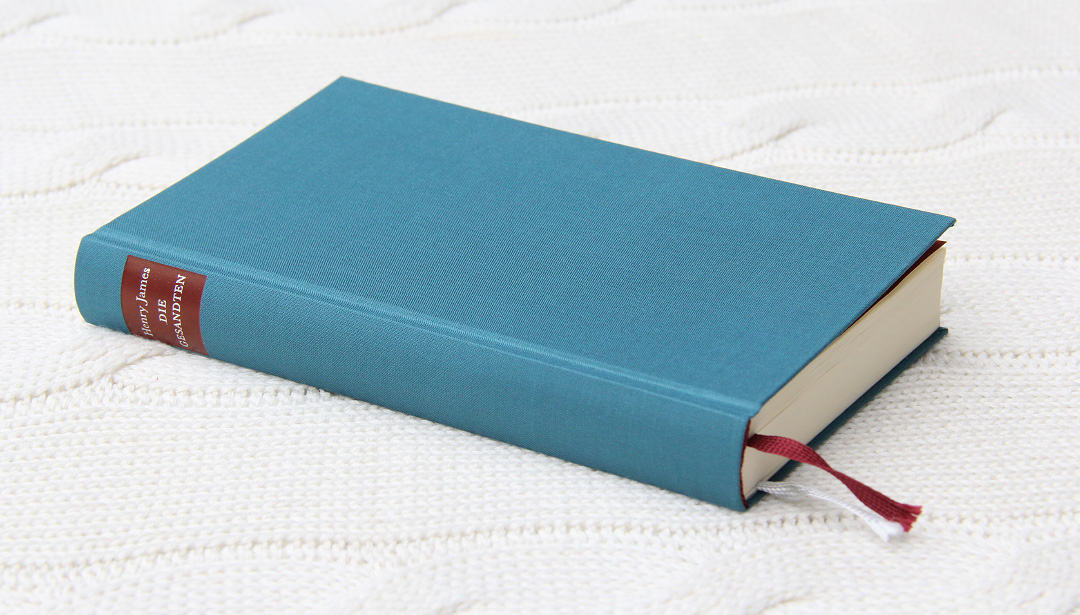

The story proper runs to 575 pages, with another 130 pages of rich notes and supplemental information—something I always enjoy. After finishing a classic, I often feel the urge to read up a bit more, and afterwords, timelines, and contextual material are a very welcome addition. With its thin paper, high-quality production, sturdy binding, and two ribbon bookmarks, you really have a beautiful, bibliophile little volume in your hands—elegant in color and finish, though the flip side is the price.

The story opens with Lambert Strether’s arrival in Chester, having come from a small American town. There, he is to meet a friend—also from America—and set off for Paris to bring Chad Newsome back home. “Home” in this case is the fictional city of Woollett, economically important but anything but a major metropolis. Chad’s mother has dispatched him to retrieve the supposedly dissolute young man and bring him back into the embrace of family and firm.

It took me some time to get used to this rambling, convoluted, and somehow peculiar style. Everything is told from Strether’s perspective: he presents himself as very decorous and composed, yet at first he doesn’t seem the brightest. Since I haven’t read anything else by Henry James, it’s hard to say whether this is his general style or a deliberate choice to characterize his protagonist. In any case, the chosen language suits this provincially minded bourgeois perfectly—fifty-five, widowed, a solid and sedate life to date—who nevertheless manages, through various encounters in worldly Paris that are quite unlike his own temperament, to navigate surprisingly well. At least, that’s how it seems, and in sum James reverses the expected picture: old Europe appears modern, chic, and gallant, while the American comes off as antiquated, plain, and not very witty. I found Strether rather taxing, and at times the book’s pace very slow. Now and then I wanted to give Strether—and his trains of thought—a shove. Compared with other books where things heat up five pages in, everything here feels ponderous and slow.

What’s interesting is that the reader initially gropes in the dark: motives, background for the journey, the characters and their thinking, their backstories and essential traits—all this emerges only bit by bit as the novel progresses. The characters aren’t laid out plainly from the start; our image of them is built up step by step. In this respect, the dialogues are pure pleasure, and however sluggish Strether’s thoughts are at first, the conversations are all the more exciting. This is surely also because the various figures present themselves as interesting people, and it’s not clear how they think and act. That uncertainty leaves a constant unknown in the narrative, and I repeatedly found myself trying to guess their motives in advance.

“[…] and he again felt the vague sensation of moving through a labyrinth of enigmatic, secret hints.” (p. 262)

This brief quotation describes the book beautifully. It’s the many small nuances—the subtleties in the dialogue and the hints—that make it compelling. Madame de Vionnet in particular is a fascinating character: multi-layered, intelligent, and gracious. Encounters with her were a delight, and the conversations had a brilliance I’ve so far only found in classics. Both the main figures and the supporting cast feel very realistic; I consistently had the sense that these were real people.

As the story progresses, Strether grows on you and increasingly takes on an observant role that suits him well. James’s protagonist is remarkable here because he is the novel’s voice, and we see the entire action exclusively through his eyes. He observes keenly, becomes quite sensitive by the middle of the book, and ponders every detail. He entertains many illusions, remains very passive, and influences events more by what he does not do than by what he sets in motion. In many places James becomes very precise, dissecting situations, thoughts, and the exact reactions of each person.

It’s fascinating how Henry James spins a fine, expansive web of relationships, gradually revealing and uncovering it as he widens the circle of characters. In this way, a very realistic social fabric emerges in which each person has his or her own drive and aims—never overblown, but entirely plausible. It’s not about grand drama, life and death, love or hate, as in many classics with sharper edges. Essentially, it’s only a question of whether Chad will return to America or not—and even that, after many pages, feels surprisingly unspectacular, because the relationships among the people increasingly take center stage, which James skillfully unveils step by step. And yet, precisely through the dialogues, which suggest many facets and also cast light on the speakers themselves, this becomes a very engaging process of development.

As readers, we get an ever clearer picture of the individuals and develop a feeling for them, much as we form an abstract sense of real people we come to know over time. We don’t remember every encounter and conversation, but we grasp what makes a person, how they are, how they react in certain situations, what they feel and think. I believe you could read the book ten times and continually discover new sides to the characters. A particularly intriguing question—more peripheral here—that recurs in literature of this period (as in Anna Karenina or Effi Briest) is the social legitimacy of a partnership between man and woman—not so much from society’s viewpoint, but in terms of its meaning for the individuals under the abstract pressure of convention.

The afterword—an essay James placed before the novel in the 1909 New York Edition—sheds light on his thinking about style, narrative perspective, characters, and of course the subject. I’d never encountered something like this in quite this form, and I found it fascinating to read, first-hand, what the author of a classic had in mind. There he identifies Strether’s realization that he has led a rather humdrum life—his sense of having failed to use his youth, of looking back on a missed time and an apparently unlived life—as the novel’s central theme. His change of heart and his illusory belief that he can make up for it make him a particularly interesting figure. James also explains that the strong self-reflection and the appearance of some characters are owed to Strether’s limited perspective. His aim was not to spoil that limitation by retrospection or by shifting narrative perspectives or narrators. Credit where it’s due: he composed the book wonderfully so that, despite the narrow viewpoint, the entire scene—the inner logic behind people’s actions, their motives, their personalities, and ultimately the whole social web—is illuminated with great clarity and becomes comprehensible to the reader.

An extensive editor’s afterword and a timeline offer insight into the novel’s development, its historical context, and Henry James’s life. As one expects from Hanser, the result is a very successful overall package. It would be presumptuous to assess the translation’s quality, but in reading the novel and notes I felt the work was very careful, and the style I would attribute to a novelist taking on this subject is well captured.

Conclusion: With The Ambassadors, Henry James presents a very deftly composed novel that, from the strictly limited perspective of its protagonist, manages to scrutinize a social fabric and its individuals in great detail, relate them to one another, and project their thinking and actions onto the main character. Particularly compelling are the excellent, lively dialogues; the multi-layered, realistic people; and the observable transformation that takes place in the Ambassador himself. In many places, though, James reflects too much, pursuing trains of thought so precisely that the novel loses momentum and becomes lengthy in spots. The sentences are intricate, long, and laden with subordinate clauses. For me there was no irresistible pull while reading, and the many hints and the wealth of information between the lines make it necessary to take real time with the book and read attentively and steadily—otherwise you can quickly lose the thread or miss details. And that is precisely the book’s strength: the subtleties of interpersonal communication within the social dance of beautiful Paris. Emotionally, too, it moved me only a little. So The Ambassadors remains a recommendation for readers who can handle a certain complexity both linguistically and thematically, who read very attentively, and who take delight in abundant dialogue and in grasping finely nuanced social relationships.

Book information: The Ambassadors • Henry James • Hanser Verlag • 704 pages • ISBN 9783446249172

Hi Tobi,

Gesellschaftsroman? Amerikanische Literatur? Da fällt mir doch gleich John Irving – einer meiner Lieblingsautoren – ein. Und da natürlich Owen Meany und das Hotel New Hampshire. Aber sind das Gesellschaftsromane? Oder eher Familienromane? Oder irgendwas dazwischen. Die Blechtrommel wird jedenfalls dem Gesellschaftsroman zugeschrieben. Also sollte Owen Meany auch einer sein – es sind ja genug Parallelen vorhanden bis zu den Initialen der Protagonisten :)

Hast du von Irving schonmal was gelesen? James schreibt ja eher aus Sicht der Oberschicht, während Irving mehr die Perspektive der Mittelschicht nutzt.Die Gesandten kenne ich gar nicht – auch nicht vom Titel her, sondern nur Washington Square und Überfahrt mit Dame. Von daher ist mir sein Schreibstil schon geläufig.

Liebe huebi,

von John Irving hab ich bisher noch nichts gelesen, vom Namen hab ich ihn aber schon mal gehört. Ich mag es ja, dem Reigen der Aristokraten beizuwohnen. Das ist schon eine coole Kulisse für rasante Geschichten, auch wenn ich nun die Verhältnisse natürlich nicht gut heiße. Aber wenn du für Irving so begeistert bist, muss ich mir die Bücher mal genauer ansehen.

So genau würde ich das mit der Kategorisierung nicht sehen. Dem Gesellschaftsroman kann man wahrscheinlich viel zuordnen und am Ende ist es nur ein Tag um sich grob zu orientieren. Washington Square gibt es in einer sehr bibliophilen Ausgabe, das werde ich mir ganz sicher noch holen. Auf “Die Gesandten” wäre ich wahrscheinlich auch nicht gestoßen, wenn es nicht in dieser wirklich hochwertigen Reihe vom Hanser Verlag erschienen wäre. Und ich muss ehrlich sagen, dass ich da noch nicht daneben gegriffen habe. Da waren bisher nur große Knaller dabei.

Viele Grüße

Tobi