A Common Story • Ivan Goncharov

I had been eagerly awaiting this new edition and translation of A Common Story. For me, it’s one of the most promising books of the year. I’ve already read Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov (English: Oblomov), which also appeared in the high-quality series Hanser Klassiker. That novel absolutely thrilled me at the time—I devoured it and loved it. Oblomov is a character study you don’t soon forget, one that belongs among the great works of literature for its eye for detail and its deep gaze into a human life. The blurb calls A Common Story “the big brother of the world-famous Oblomov,” which certainly sets the bar rather high. It was also translated by Vera Bischitzky, a renowned and award-winning translator. All the conditions point to a first-class reading experience. Whether I found in this book Oblomov’s big brother—you’ll read in this review.

The young Aleksandr Fyodorych decides to move from the countryside to the capital, St. Petersburg, to start a career there. He stays with his uncle, Pyotr Ivanych, and Aleksandr’s youth and inexperience quickly become apparent. The world of Petersburg reveals itself as disillusioning, and Aleksandr encounters his uncle’s sober, calculating worldview—which gradually proves to be the reality of life.

The book starts slowly, describing Aleksandr’s departure from his family’s country estate. It’s reminiscent of Oblomov, which also begins at a gentler pace. Even when Aleksandr isn’t at the center of these opening scenes, Goncharov uses the introduction cleverly to characterize his protagonist. I love these depictions of rural life in Russia at the time; they always have a unique atmosphere, strongly recalling Rousseau’s “return to nature” and conveying an ideal that never truly existed—and certainly wasn’t so picturesque for the servants as it may appear to a reader today. The story then quickly gathers speed, and I tore through the following pages with surprising ease. Aleksandr’s drifting in the capital, his search for meaning—this is, of course, very typical of a Russian author.

I especially liked Aleksandr’s uncle. He’s a true realist who values feelings very little and thus serves as a counterpoint to the sentimental, dreamy Aleksandr. It’s a bit like The Big Bang Theory, where the uncle corresponds to Sheldon Cooper and Aleksandr’s counterpart would be Leonard. The uncle is very clever, sees through Aleksandr’s doings in detail, and is clearly his superior. Aleksandr, by contrast, dismisses rational decisions and is a weather vane in the winds of passion. Goncharov admittedly exaggerates his figures, but it’s simply entertaining to read what situations Aleksandr gets himself into and how his uncle, in particular, advises him and analyzes his behavior completely. I found the dialogues between the two especially well done and entertaining. Overall, the course of the story was not very predictable. It’s also well handled how beautifully Goncharov changes Aleksandr over the years—how experiences cling to him and how he repeatedly contradicts himself. Toward the end, however, the figures and their thinking felt a bit constructed. In their views and behavior, the characters seem oriented toward illustrating a worldview, and I repeatedly had the sense that they were novelistic figures rather than real people. The life philosophy is coherent, though, and the book and its depicted story are realistic and convincing as a whole.

The book reads very smoothly, and you repeatedly encounter beautiful sentences. In tempo and style it recalls the French authors, and here too there are emotional love adventures, though not with the intensity unique to the French. With the pleasant style and brisk pace, both the story and the protagonist develop at just the right rate. As the notes reveal, Pushkin inspired Goncharov greatly, and there are numerous allusions to poems and texts by the great, celebrated writer. The book had me truly engrossed; whenever I picked it up, it was hard to put down. It’s simply exciting to read what becomes of Aleksandr and how his experiences change him. In doing so, Goncharov—very typically Russian—poses the big questions: about the value of love, of society, of human striving, and the meaning of life. Aleksandr even gives himself over at times to that Russian languor, though not with Oblomov’s perfection. The blurb’s reference to what is “typically Russian” fits perfectly here, and I enjoyed that aspect immensely. You’ll find all the elements so characteristic of the great Russian authors: from rural life and the grand search for meaning to that distinct Russian lethargy, the vastness of the steppe, love stories in just the right measure—all seasoned with reflections on the big picture.

A Common Story was published in 1847—thirteen years before Goncharov’s Oblomov. When Aleksandr lies lazily on his divan, you can already see early ideas leading toward the later masterpiece. Still, the parallels are limited, and Aleksandr’s fate is different, even if it’s characterized just as deftly. Like Oblomov, Aleksandr changes over the course of the story; he experiments and reflects on his life. In how this happens, Goncharov’s hand is unmistakable. What I also find lovely and noteworthy in his style is the humor that keeps shimmering between the lines. As readers, we sense that Goncharov is always exaggerating just a little. Although the book radiates a certain seriousness through its depth, you can’t help but smile—from the uncle’s quips to the way Aleksandr slips back into old patterns. When a hot temptress appears around the corner, his lofty thoughts and resolutions are quickly forgotten. And the uncle himself doesn’t always hold to his own aphorisms that strictly.

Goncharov was born in 1812 in Simbirsk—practically the provinces, a small backwater. The notes indicate that the novel has autobiographical features, with clear parallels to his own path. When Goncharov lets Aleksandr discover Petersburg for the first time, it feels very real; the impressions are likely the author’s own. In turn, Goncharov looks at the provinces from a city-dweller’s perspective, and these cultural differences nicely highlight people’s particular traits at the time. There’s a distinct mood to it. That’s precisely Goncharov’s aim, and his novels offer a fine portrait of Russia in his era.

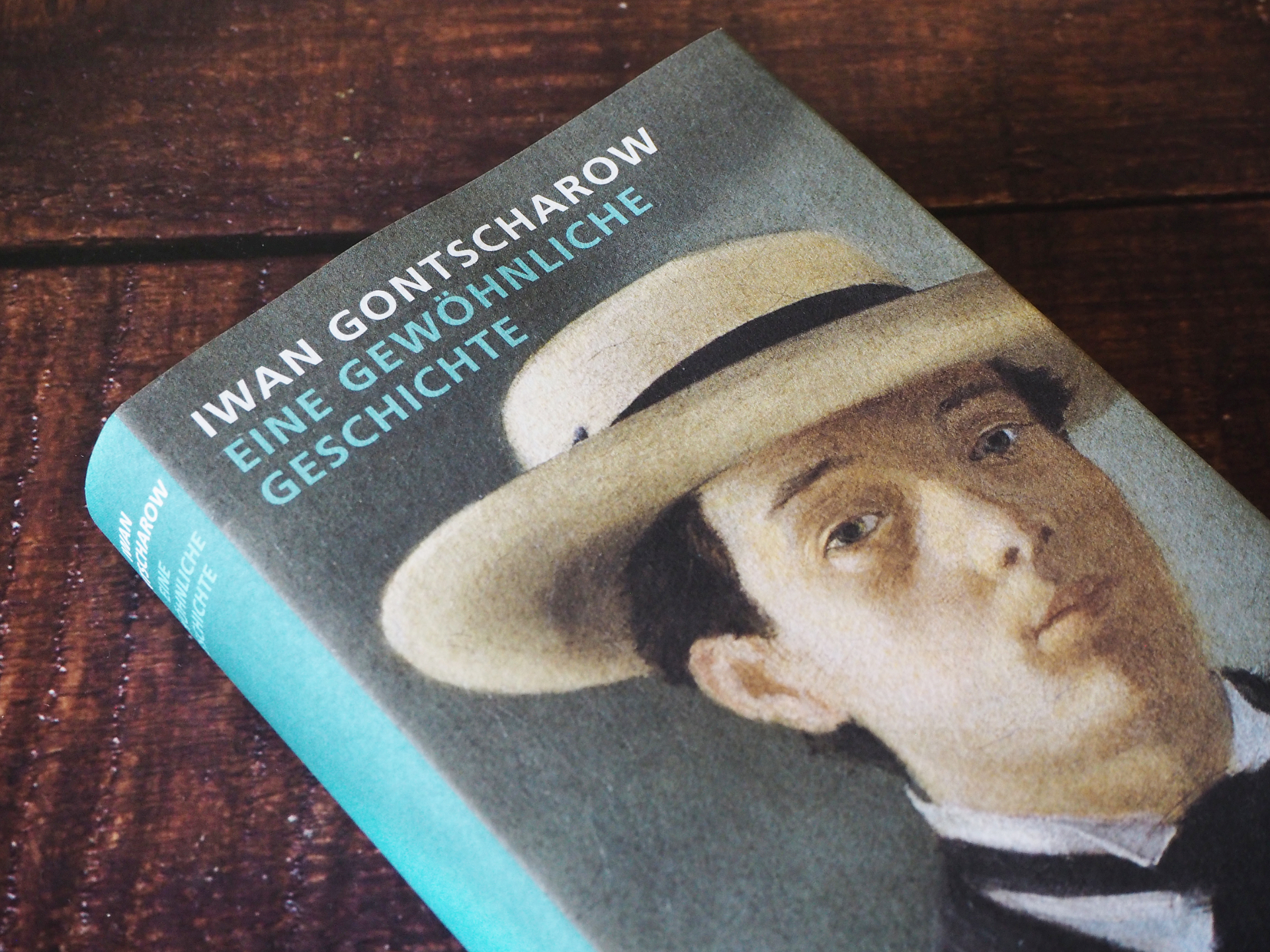

The book as an object is once again a delight. I already knew the latest releases in the Hanser Klassiker series and had read them in other editions. This Goncharov volume, however, was a bull’s-eye, and I had almost forgotten what a pleasure Hanser’s beautiful books are. The jacket is made from a slightly heavier paper; as usual, the book is bound in sturdy linen with thread stitching, and altogether it simply feels good in the hand—opening it, running your fingers across the cover. It’s exactly the right size, and with its two ribbon markers, abundant notes, and afterword, it offers the premium quality one so rarely finds these days in such perfect form. The colors of the two ribbons are especially lovely, contrasted beautifully and echoing the dark turquoise tone of the cover paper. The typography, too, makes for a comfortable read. What can I say—without such wonderful books, the world would be less beautiful and life less worth living.

Translator Vera Bischitzky, as mentioned at the outset, is very experienced and delivers a highly pleasing prose that captures the tone of the story beautifully. Remarkably, she leaves words without adequate equivalents in the original or supplies a note. Thankfully you won’t find things like “little father” (batyushka) or “little mother” (matyushka) here, as in many older translations—something I noticed very early while reading. It didn’t surprise me that Bischitzky explicitly discusses this in her translation notes and gives examples of why choosing such ill-fitting words would be wrong. I also found some of her comments on the translation in the afterword very interesting—she shares a bit of behind-the-scenes detail, and you can see the dedication and high standards that went into this book. She read the novel aloud several times to find the right rhythm and to achieve an effect that sounds more spoken than written—just as the original does. This strong focus on rendering the original work as faithfully as possible is exactly what distinguishes today’s best new translations.

The afterword itself is somewhat brief but reveals several interesting details. For example, the novels A Common Story, Oblomov, and The Precipice (Die Schlucht) form a trilogy in which Goncharov set out to portray different Russian eras and their transitions. She also writes about Goncharov’s literary life, noting that for him the prerequisite for writing was to recount what he himself had experienced and observed.

Conclusion: I raced through this lovely book and could hardly put it down. A Common Story is once again quintessential 19th-century Russian literature: from simple country life with its original characters to the big questions of life’s meaning, love, and society. I still found Oblomov a good notch better—particularly because its figures are drawn even more beautifully and convincingly—but A Common Story is likewise of the finest quality. This edition, translated by an outstanding translator and presented with perfect production values, leaves nothing to be desired—just as we’ve come to expect from Hanser’s series. A wonderful book and a clear recommendation. For anyone with a soft spot for Russian authors, or for those who loved Oblomov, it’s essential reading. But I can also recommend this very common story to everyone else.

Book information: A Common Story • Ivan Goncharov • Hanser Verlag • 512 pages • ISBN 9783446269255

Hallo Tobi,

das klingt wieder nach einem Klassiker ganz nach meinem Geschmack! Ich wollte sowieso mehr russische Werke lesen.

“Ich liebe ja diese Darstellung des ländlichen Lebens im Russland der damaligen Zeit.”

Das geht mir ganz genauso. Die Szenen mit Lewin in “Anna Karenina” haben sich damals nachhaltig bei mir eingeprägt. Wobei ich finde, dass dieser Zauber des ländlichen Russlands seine Wirkung erst dann richtig entfaltet, wenn man als Kontrast dazu das oppulente Treiben der Großstädte präsentiert bekommt.

Liebe Grüße

Kathrin

Liebe Kathrin,

das Buch könnte schon sehr was für Dich sein. Wenn Du aber Oblomow noch nicht gelesen hast, dann gibt ihm den Vorzug. Natürlich ist da auch wieder russisches Landleben mit dabei, aber eben auch der extrem geniale Oblomow ;)

Stimmt, an die Szenen in Anna Karenina, wo er dann bei der Heumahd dabei ist und mit den Bauern zusammen arbeitet, also daran kann ich mich auch erinnern. Anna Karenina muss ich auch echt nochmal lesen, das war schon top das Buch.

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Okay, dann wandern also direkt beide Titel auf die Merkliste. :D Von Gontscharow hab ich tatsächlich noch gar nichts gelesen und bin gespannt darauf, seine Titel zu entdecken.

Hi Tobi,

du lobst die Qualität der Hanser-Reihe ja sehr.

Dazu eine Frage: Wie dick ist das Papier hier?

Ich war neulich mal im Buchladen und hatte ein paar der Hanser-Bücher in der Hand. Bei jedem Umblättern hatte ich Angst, die Seite zu zerreissen. So dünne Blätter habe ich selten gesehen. 500 Seiten wo andere Bücher der selben Dicke 150 Seiten haben. Das war dann schon krass.

Insgesamt super Verarbeitung, klar, aber alleine dieser Punkt war für mich als Argument gegen einen Kauf zu stark.

Lieber Florian,

die Bücher der Hanser-Reihe sind alle ungefähr gleich dick. Was dann immer variiert ist die Papierdicke. Bei “Krieg und Frieden” ist es Dünndruckpapier, wobei ich damit nie Schwierigkeiten hatte oder es mir eingerissen wäre. Der Vorteil ist eben, dass ein 1000 Seiten Buch trotzdem ein angenehmes Gewicht hat und schön handlich ist. Nur Chips sollte man dabei nicht essen, von Fettfingern wird das Papier so durchsichtig und das geht dann auch nicht mehr weg.

Bei den Hanser-Klassikern die etwas weniger umfangreich sind, beispielsweise jetzt dieses Buch oder auch beispielsweise “Der scharlachrote Buchstabe” (die haben so um die 500 Seiten) da sind dann auch die einzelnen Seiten etwas dicker. Aber wie schon gesagt, ich mag die Dünndruckseiten schon auch echt gerne und wenn ich “Krieg und Frieden” in die Hand nehme, dann sieht man trotz S-Bahn-Fahrt-Lesesessions nicht, dass ich die Bücher schon gelesen habe.

Herzliche Grüße

Tobi

Danke dir.

Das ist dann wohl persönlicher Geschmack.

Ich hasse Dünndruck wie die Pe- wie Corona. Vor allem dann, wenn überall die nächste Seite durchscheint. Unlesbar.

Am Rande: Woran könnte es liegen, dass das Kommentarformular eigentlich meinen Namen nie speichert? Andere haben ja auch immer ihren Avatar dabei.

Hallo Toni,

per Zufall bin ich auf deinen interessanten Blog gestoßen und habe mich ein wenig eingelesen.

Ich bin ebenfalls ein Fan der Hanser Klassiker und besitze einige davon.

Nach dem Oblomov ist ja nun auch ‘Eine alltägliche Geschichte’ erschienen. Weißt du zufällig, ob auch der dritte große Roman von Gontscharow, ‘Die Schlucht’, neu übersetzt bei Hanser erscheinen wird? Der ist zur Zeit ja leider nur in einer älteren Übersetzung antiquarisch erhältlich.

Viele Grüße

Konrad