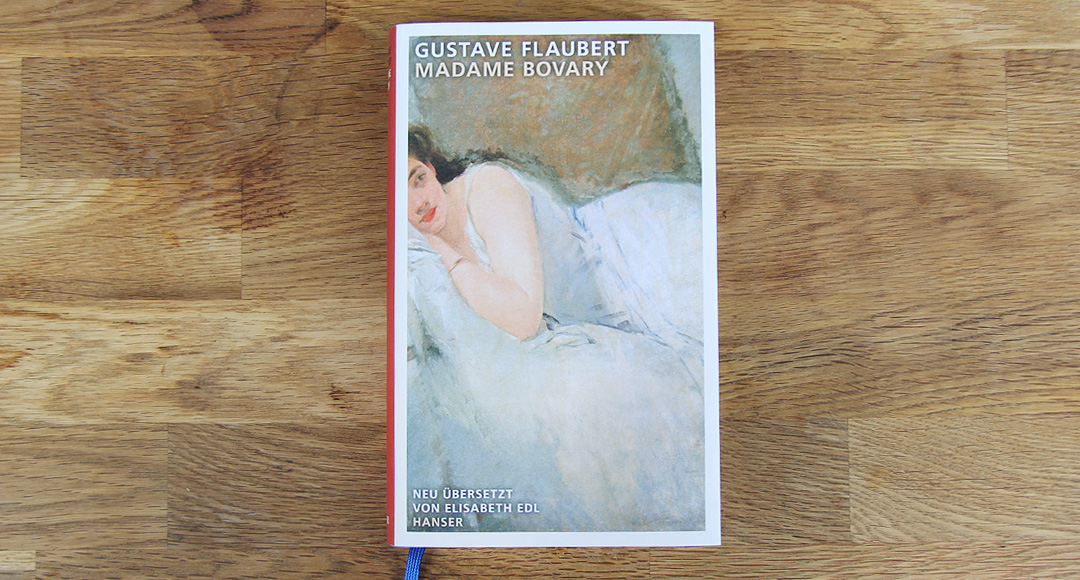

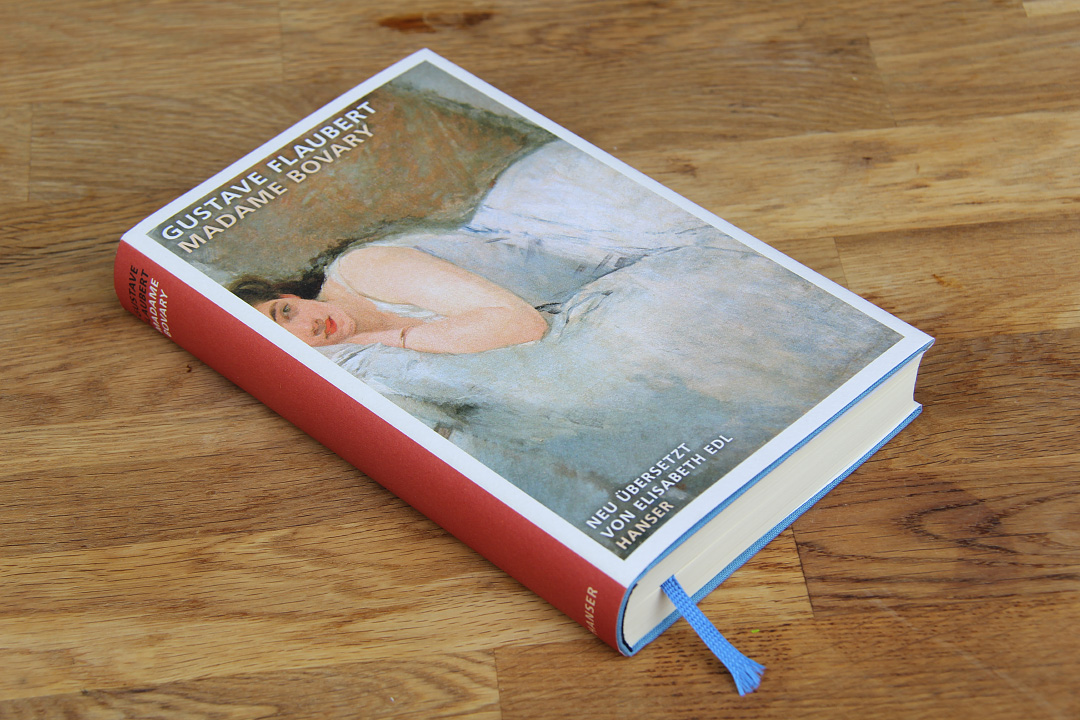

Madame Bovary • Gustave Flaubert

I don’t know why, but the topic of adultery is simply fascinating—especially when it comes to novels from the era of Realism. Anna Karenina was already a true masterpiece in this regard. So I approached Madame Bovary with high expectations. However, the first fifty pages were quite straightforward and unadorned, and I feared I had made a poor choice. In hindsight, that fear was unfounded, because those opening pages are devoted to Emma’s husband, Charles Bovary, whom Flaubert portrays as rather dull. The novel truly begins to gain momentum only after Charles marries Emma and the perspective shifts to her.

Her real introduction begins with a depiction of her childhood in the convent, written with such eloquence that I was, and still am, completely enthralled. A quote from that passage:

So she let herself be carried away by Lamartine’s meanderings, listened to the harps on the lakes, to the songs of dying swans, to the falling leaves, to the pure virgins ascending to heaven, and to the voice of the Eternal resounding in the valleys. (p. 51)

Flaubert’s language is simply extraordinary. His sentences are so beautifully crafted that I often paused to reread them—some of them over and over again. It’s almost like listening to music, full of vivid and colorful expressions. Here’s an example of such a sentence, flowing like a string orchestra beginning a gentle overture before losing itself in its main theme:

She flung herself upon it, clung to it, carefully poked at the embers that threatened to go out; she sought everything that could fan the flame; and her most distant memories as well as her immediate troubles, what she felt and what she imagined, her longing for pleasure that overflowed, her dreams of happiness creaking in the wind like dead branches, her fruitless virtue, her stunted hopes, the misery of her home—she gathered it all up, took everything, used everything to stoke her sadness. (p. 167)

Given the similar time frame, it felt only natural to compare Emma’s story with that of Anna Karenina as I read. While Anna is swept away by her love for Vronsky without actively seeking it, Emma is consumed by her longing for romantic love—an idealized notion of love that grew during her time in the convent through forbidden books passed among the girls and through her own temperament. It nearly turns into an unrestrained craving. Like Anna, Emma resists these feelings. She seeks answers in literature, in her daily life, and even makes a tentative yet passionate attempt to find solace in faith. What’s fascinating is how Flaubert depicts her thoughts—so realistic and relatable, often all too human—when Emma’s emotions blend together until neither she nor those around her can make sense of them:

Now the cravings of the flesh, the thirst for money, and the melancholy of passion fused into one single pain […] (p. 147)

Moreover, she now hid everything beneath such indifference, had such tender words and such proud glances, such erratic behavior, that selfishness could no longer be distinguished from charity nor corruption from virtue. (p. 283)

Flaubert portrays Emma as fickle and lacking perseverance, marked by a strong egocentrism, particularly toward her naive and good-natured husband. As the novel progresses, her behavior becomes increasingly reckless and greedy. The resulting picture of her is exaggerated—perhaps not entirely unrealistic, but pointing to extreme traits of character. One quote captures her essence perfectly:

[…] and the sweetest kisses left on her lips only an unquenchable longing for greater pleasure. (p. 369)

Although Emma’s faith is addressed at times, she elevates romantic love—and the pursuit of it—to the level of her religion. Her life’s goal is to find true love and, through it, to discover the beauty of the world—something that, for her, involves an extravagant life of travel, balls, luxurious dresses, and lavish consumption. In this glorification of romantic love, Flaubert seems to raise a warning finger. This reminded me of an article recently published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), which notes that our modern society shows a similar tendency to idealize love in a somewhat self-indulgent way. In her adultery, Emma does indeed find, at least at first, the fulfillment she has longed for:

Now she thought of the heroines of all the books she had read, and the sweet host of those adulterous women sang in her memory with sisterly voices that enchanted her. She herself became part of those fantasies, realizing the endless daydreams of her youth, for she saw herself in that image of the loving woman she had so passionately envied. Moreover, Emma tasted the satisfaction of revenge. Had she not suffered enough? But now she triumphed, and the love so long suppressed gushed forth like a joyful spring. She drank it in without remorse, without fear, without doubt. (p. 216)

Flaubert’s linguistic mastery also shines in a beautiful passage describing an agricultural fair that Emma attends, during which she draws closer to one of her lovers. Flaubert intertwines the official speech—honoring the most loyal and hardworking peasants—with the emotional, desire-laden dialogue between the two lovers. This contrast, and the interplay between the lines, reminded me strongly of Tolstoy—or of Bach’s fugues—because it creates a polyphonic dialogue where each individual voice is harmonious in itself, yet together they form a richer and more profound composition.

Quite early in the novel, Charles and Emma settle in Yonville, a small provincial village. Particularly remarkable is the depiction of the other villagers—such as the apothecary Homais or the merchant Lheureux—whose presence places Emma’s actions in a broader social context, at times amplifying and at times softening their impact. As readers, we gain a vivid insight into the mindset and life of the bourgeois class of the 19th century.

The novel was serialized in the magazine La Revue de Paris and censored; Flaubert was prosecuted for “offenses against public morality” and for “glorifying adultery,” but was eventually acquitted. The edition published by Hanser Verlag includes an extensive afterword and the full text of the indictment—fascinating to read, as it provides a revealing glimpse into the moral values of that time.

Conclusion: The linguistic perfection, the sensitive portrayal of Emma—both understandable and emotionally tangible—paired with the distance we maintain from this seemingly unrestrained adulteress, make this novel a masterpiece. The way Flaubert brings scenes and characters to life, his precision and construction, his melodic phrasing, the way he paints landscapes, settings, and fleeting moments with his wonderful language—all invite rereading and offer pure delight. A book I can recommend to everyone.

Book Information: Madame Bovary • Gustave Flaubert • Hanser Verlag • 760 pages • ISBN 9783446239944

Hallo,

da schaue ich mich hier zum ersten Mal um und finde zu Beginn sofort eines meiner Lieblingsbücher. :)

Ich hoffe, dass es nach Deiner tollen Beschreibung noch viele Leser finden wird!

Liebe Grüße

Ute (Liedie40)

Hallo Ute,

hui also wenn das Buch eines deiner Lieblingsbücher ist und du im #TeamTolstoi bist, dann musst du echt einen Blog starten. Scheinbar hast du einen echt guten Lesegeschmack!

Ich hoff dir gehts schon besser!?

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Hallo Tobi,

Wie geht es dir?

Wie läuft es mit der Buchparade?

Lg

Anne

Huhu Anne,

mir gehts gut. Hab schon auf Twitter gesehen, dass du eine kleine Blogrunde machst ;)

Die Blogparade läuft leider nicht so gut. Glaub mein Blog ist noch zu unbekannt.

Liebe Grüße und ein schönes Wochenende

Tobi

Hallo Tobi!

Mensch, ich bin gerade durch Kerstins Blog hergekommen und bin total begeistert, dass ich einen Blog entdeckt habe, auf dem auch so grandiose Klassiker rezensiert werden! Ich liebe Tolstoi und Flaubert und finde deine Rezension zu “Madame Bovary” ganz wunderbar. Auf Deutsch habe ich das Buch, ehrlich gesagt, noch nicht gelesen, aber auch auf Französisch ist der Schreibstil unvergleichlich aussagekräftig und gewaltig. Eines meiner liebsten Buchzitate stammt aus “Madame Bovary”. :)

Ich werde von nun an auf jeden Fall häufig hier vorbeischauen, fühle mich schon jetzt wohl auf deinem Buchblog!

Liebe Grüße

Saskia

Hallo Saskia,

vielen Dank für dein nettes Kommentar. Ich hatte schon die Befürchtung, dass eine Rezension zu einem Buch wie “Madame Bovary” nicht so gefragt ist und bin überrascht, dass doch viele diese Klassiker einfach schätzen.

Klasse, dass dir mein Blog gefällt. Hast du auch erst mit dem Bloggen angefangen? Wenn du Klassiker oder eher unbekannte Bücher magst, dann solltest du auch darüber schreiben. Mich würden solche Tipps echt interessieren ;)

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Hi Tobi,

ja, richtig, ich habe Anfang Januar mit dem Bloggen begonnen. :) Klassiker werden auf jeden Fall noch ein Thema sein. Ich überlege aktuell noch, mit welchem Klassiker ich beginnen soll (es gibt einfach zu viel Auswahl!).

Liebe Grüße

Saskia

Hallo Saskia,

da bin ich gespannt, worüber du noch so bloggen wirst. Bei mir wird das schon ein Mix aus aktueller Literatur und Klassiker werden. Mal sehen, eben worauf man gerade Lust zu lesen und zu schreiben hat.

Freu mich schon auf deine nächsten Beiträge.

Liebe Grüße

Tobi