Horcynus Orca • Stefano D'Arrigo

As part of the Leipzig Book Fair’s blog sponsorship, Horcynus Orca has already caused quite a stir in the blogosphere, generating a fair amount of attention. I had come across this classic—which has been translated into another language for the first time—earlier and wondered what might be hidden behind this book.

This will probably be the most extensive review I have written here so far. I read Horcynus Orca very intensively; I plunged into this book with skin and hair and returned with so many impressions that I want to share quite a bit about it with you. So I ask for your patience that this post has become so comprehensive. By now I’ve been writing it on and off for over a month, and that brings together a lot of impressions.

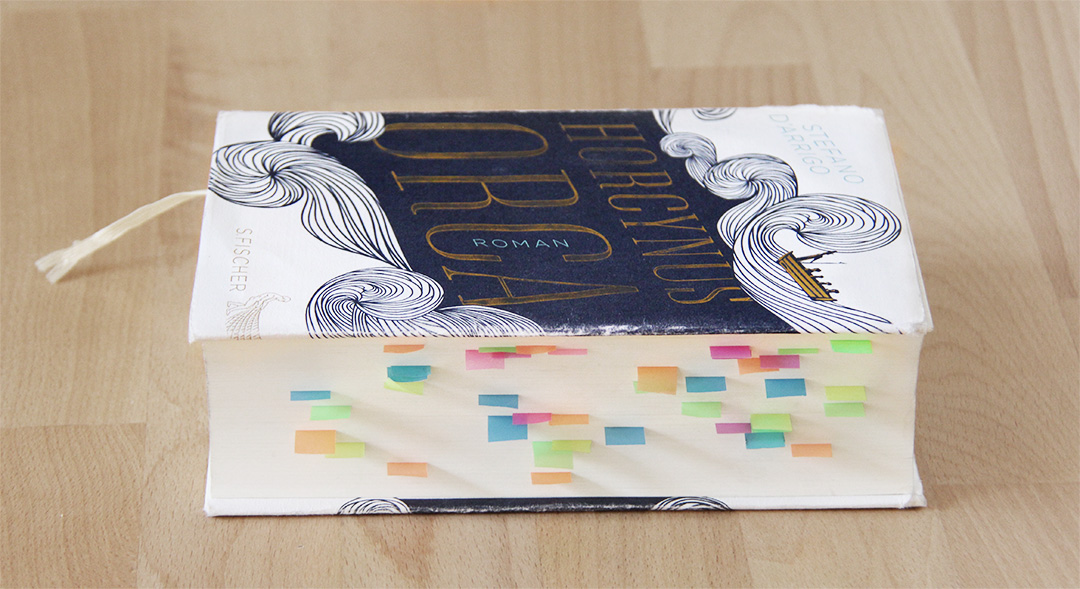

Here you can see a picture of my copy and the many passages with truly magnificent sentences that I marked. I always copy down good sentences again, and with this book there are several pages of them.

The book is about the Pellisquadre, the fishermen of Sicily—more precisely the fishermen of Charybdis, on the strait between Calabria and Sicily, where the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Ionian Sea are connected by the narrow Strait of Messina. A region steeped in legend and thus an excellent setting for an epic about the sea.

For a long time this novel was considered untranslatable, until Moshe Kahn, a luminary in the world of translators, took on the work and rendered it from Sicilian-inflected Italian into German. With 1,500 pages printed on thin paper, densely set, and weighing 1.5 kg, the book is anything but a lightweight read—both in the physical and figurative sense. Linguistically and in terms of content, this novel is demanding, and it reveals its grand, powerful world only to the reader who approaches it with a certain degree of dedication. What that means is what I want to explain more closely in this review.

Horcynus Orca is a book that does not reveal itself to the reader immediately, that does not impose itself, and certainly is not ingratiating. A quality that contemporary works often deliver in abundance; with this book you hold a story in your hands that must be discovered, one the reader must dive into and mentally attune not only to the protagonist but also to the often very alien-seeming figures. I felt a distinct cultural gap while reading, arising from the fact that the people in it often have a completely different way of thinking. The sea—and the high degree of belonging these people feel toward it—creates another way of thinking and feeling. Thus the statements, behavior, and actions of the fishermen or, for example, the Feminoten often seem somewhat strange. That’s part of the appeal, because it’s an adventure in itself to penetrate a completely different mode of perception, and if you immerse yourself deeply enough in the characters’ narratives, you begin to understand them.

The book employs its own unusual and artful language. This is a distinctive feature and has indeed brought D’Arrigo some criticism. A translation was therefore very problematic, seemingly impossible, and so Moshe Kahn, the translator, “recreated” the book over more than 10 years of work—reshaping it, occasionally departing from the original to achieve similar effects (cf. the translator’s afterword from p. 1461). Judging the success of this endeavor objectively is probably only possible for those who have read the book in the original. But what did this very particular and unique poetry mean for me as a reader—one who feels the effect and melody of the sentences and does not, with an academically trained gaze, rediscover the many linguistic elements of Sicilian, “shaped over nearly two millennia into the linguistic forms of the Italian South” (p. 1467)? First, I had to immerse myself in the book’s own, utterly new language. I read the first 50 pages, and then I read them again. Only from page 100 onward—pages for which I needed three times as long as usual—did I arrive, on the linguistic level, in this epic. It reminded me a little of the enjoyment of classical music: you have to listen more than once, get to know its main theme, and when you have a sense of which tones will sound, you can delight in the fact that they repeatedly don’t—surprising you while remaining within reach. That’s exactly what this text is like. At some point you’re seized by a current that pulls you into this book, because the sentences have a melody all their own. Why is that? I suspect two reasons. First, the sea is always and everywhere present—metaphorically, as a backdrop, as the absolutely fundamental basis for the thinking of ’Ndrja and the people he meets. A second reason is the war and the vehemence, the remorselessness, the unimaginable that enters people’s lives with it; there could be no more striking, clearer, or more frightening way to convey this than through the thunderous, dreadfully calm surf of the flowing language. Several times I had to pause in shock at these formulations. Here is a quotation about the Feminotinnen—self-confident, rough, self-determined fishermen’s wives who keep themselves afloat by smuggling salt and with much, at times almost nihilistic, pragmatism:

To imagine seeing them there, the old man told him, he should narrow his eyes as if to sharpen them and cast them upon those magnificent women stretched out there, to see them there and admire them in their Olympian calm, which they maintain in these end-time events, like immortals whom no cannon ever reached: there, far and unattainable, on the bed behind the door, as if in caves without echo, where they thought of the boat they had hauled ashore, safely stowed beneath their behinds, and where with their fingernails they stroked and prepared the place beside them, as if dragging the man into the house by the hair, onto the bed, into the homely hiding place of their bodies, by the hair, full of rage, out of this bastard war without love or salt, about which they therefore didn’t give a damn. (p. 142)

The book has many historical and cultural references that can probably be grasped even better with background information on the period and place—such as the Mussolini regime, its symbolism, and its influence on society. These are usually explained in somewhat more detail within the story and often arise from the context. On a second, much more important and pronounced level, however, the author describes the people—their pain and hopes—and gives them ample, ample space to convey these to the reader. With great verbal power, with beautiful, apt sentences, with metaphorical interludes, sometimes tentative, sometimes with an almost coarse-seeming directness. And always together with the sea—the untamable sea with its natural forces—which governs the fate of these people as uncontrollably as the war does.

And for the beach vagabond it must be, every time, as if he were standing right before death and remembering the time lived and seeing his whole life again, as if the sea were pouring it over him, wave upon wave, there before him on the beach, year upon year, under the lashing spray, which lasts only moments. (p. 160)

Unknown words and neologisms are explained within the story, usually also with their delicate meanings. I read over some of the neologisms; some you absorb unconsciously and understand well enough in context. Others, however, formed only a very abstract image for me—like the word “schampanjerselig” or Arkelamekk—roughly the way one has a feeling for mathematical relationships but would find it hard to explain them, such as the intersection of two bodies in eight-dimensional space.

There are a multitude of words used very frequently in the book that are entirely unfamiliar before reading. One example is the term Fere, the fishermen’s name for the local dolphins. In Sicilian this outdated, no longer common term means something like “fish-beast.” That is how the term is explained in the book; in the appendix it is derived from the Latin ferus, meaning wild, untamed, cruel. For the fishermen, dolphins are a major problem because they destroy the painstakingly knotted fishing nets—the fishermen’s livelihood. A large part of the book is therefore also dedicated to the struggle or war between the fishermen and the dolphins, in which the nuances of this problem and the linguistic use of Fere and dolphin are discussed, while at the same time creating another parable for the war of the Fascists.

It is very interesting how D’Arrigo derives this parable—how the connection is presented with great complexity, almost like a deductive chain of argument, shaped by history and philosophy, and always clad in the garb of the sea. D’Arrigo suddenly begins to tell of the sea creatures, the Fere—how they live and how it is a mystery how they die of old age, and that no fisherman has ever seen an animal that perished from great age. From this opening, which spans many pages, the author describes how the protagonist ’Ndrja loses himself in a daydream. He dreams that he discovers the Fere swimming to an active volcano and seeking voluntary death in the flames of the eruption. Through this martyrdom, ’Ndrja elevates these animals, hated by the fishermen, into something higher, something pure and glorious. Suddenly the negatively charged, outdated term Fere is no longer used; instead, the word dolphin appears. In an immediately subsequent daydream, ’Ndrja imagines revealing this to the other fishermen from his home. But they do not want to hear his words; in a vivid comparison they trample the dolphins underfoot. D’Arrigo goes further back and describes some scenes from ’Ndrja’s past as a fisherman and soldier, which explain his ambivalent relationship with the Fere. In the end he lets all these fragments flow together, and then it becomes clear to the reader why he does this: all these experiences, thoughts, childhood memories—all these individual stories and scenes—are part of ’Ndrja’s self-understanding and his worldview, and whoever wants to understand the soul of this fisherman with all its facets is given the foundation here.

The detested Fere, which the Fascists lovingly call dolphins, are a parable for Mussolini and his regime, for fascism and the false glory in which it clothes itself. The Fere thus bears several layers of meaning and plays a comprehensive role in understanding ’Ndrja’s inner world. It is a mirror of his struggle with himself, a wrestling with the war he has known—in which he has, in a subtle way, made peace with the Fere—and his return home to his original soul, which despises the Fere to the core.

It was as if he were returning there, farther than even the time and place to which he already saw himself returned, there, into the now, to the shores of the Feminoten country: returned from the war, which was a war, and different from their war; returned from the high seas of the continent, where nothing is known of the Fere, where only the dolphins are known, and he had come to know them too, which now, in a head gone wild from sleep, rise up like terrible apparitions—shortly: returned from everything that had driven him away from the sea between Scylla and Charybdis and estranged him from the usual time, from the usual war against the Fere. (p. 213)

What is fascinating is how D’Arrigo, with great verbal power, links these parables—each drawn from the marine world—to the characters and their fates, and how he brings the fishermen’s personalities to life and weaves them into their environment. And this shows something else impressively: ’Ndrja sees the world through his own eyes, those of a sailor and fisherman. There is no truth; what appears so clear and unambiguous to our minds is only an image of reality and lays no claim to validity. It is the whole influence of our prior life that always distorts our view in one direction or another.

Another example of these deductive chains of argument that at times elicited an aha moment in me is the description of the scene in which ’Ndrja’s unit capitulates, scuttles its own ship, and sets off for home. For almost a hundred pages, D’Arrigo describes how the concept of the siren (for a mermaid) shaped ’Ndrja’s youth and coming of age. Not boring or monotonous—no: with sweeping yet interesting scenes from the fishermen’s lives, with striking images of the mystical sirens. Only to show, in the end, with what clarity the decision to capitulate was made and how closely this decision is bound to the fishermen’s soul.

What do I want to say with this detailed description of these elements from the book? It is a pleasure to read, and even though D’Arrigo often writes very expansively, there are usually several meanings underlying his passages—some that present themselves surprisingly clearly and understandably, others that emerge only after longer reflection. The text is so multifaceted that there is surely much more within it that will likely reveal itself only upon a second or third reading. From about page 100 I somehow, unconsciously, grasped this mode of writing and could then follow it easily—floating along on the very long sentences that usually stretch over a quarter of a page, riding the swells of the language so similar to the sea. From about page 300 I then understood how this book is structured from a macroscopic perspective and why it is considered such a significant work. What D’Arrigo composes here is laid out on multiple levels of abstraction and produces a psychologically, frighteningly true portrait of the fishermen—people who could hardly be more distant from me culturally and historically, yet who suddenly feel very close.

The story also largely consists of the portrayal of the various characters whom ’Ndrja encounters, with D’Arrigo crafting a very clear picture of each person. This is made up of what they tell, but especially how they tell it—how they interact with their environment while doing so, and the body language with which it happens. I often had the impression that what I read unfolded in real time—in other words, the events occurred roughly as quickly as I needed to read them. That may sound long-winded, but because of the complexity of these characters I never grew tired of it.

Through these encounters, the clear trail of the war becomes visible and, in a rather subtle way, it reaches the reader. You learn, apparently in passing, that in the strait between Sicily and Calabria numerous fallen soldiers drift along in the current—repeatedly washing ashore, sometimes carried to the coast by dolphins. Or you sense the grief of the women left behind, whose men, with great enthusiasm, went off to the Fascists’ war and now are exposed to everyday horrors—perhaps to find their own washed up there along the shores. The inner struggle accompanying all these people can be found somewhere between the sea’s swells, for it is omnipresent in the lives of these people and in this book (a fact I simply have to keep emphasizing because it is so significant that it keeps forcing itself to the fore—even in this retrospective).

The book is divided into four parts. The first covers the journey home and describes the bloody trail of the war that ’Ndrja encounters along the way. The second part is devoted to ’Ndrja’s father, Caitanello, who recounts what happened during the war. In some expansive explanations by D’Arrigo, the reader also learns a great deal about ’Ndrja, his youth, and the life and culture of the fishermen. The third part then describes the orca—the Orcinus orca, the great killer whale—in great detail. The fourth part deals with how the war changed the people, society, life—and the fishermen themselves.

While ’Ndrja remains more in the background in the first part and the stories of the people he meets on his return take center stage, he moves much more into the foreground in the second part. His way of thinking and acting was, for me, easy to follow here, and only from this point could I really empathize with ’Ndrja—also seeing how the war changed the fishermen’s fragile habitat and how great an influence it had on the region. It also becomes clear how backward Sicily was at the time. At this point, too, I was very impressed by the clarity and imagery with which D’Arrigo describes the war:

In the blink of an eye the whoremonger-soldier [a metaphor for the war at the front] came again to sun-heated strength and struck about with catastrophes: dead, wounded, torn-off limbs, flames, explosions, ruptured bodies, foaming waves of blood, smoke and black craters, screams and whimpering—German and Italian, American and English lament—which at this point, however, all emitted in the same language; they all wore the same uniform, they all died the same death, they all fell by the hand of the whoremonger-soldier heated by the sun. (p. 579)

In the second part, in the stories told by Caitanello, ’Ndrja’s father, the experiences are narrated very extensively from his perspective. It’s understandable why D’Arrigo ranges so widely, and the picture of the fishermen that you gain is very detailed; yet I think, as in a few places in the book, somewhat less text would probably have sufficed to give the reader a comprehensive picture. In addition, the book no longer seemed to have such a clear thread here. The stories, which reach into the near and somewhat more distant past, often feel expansive. For example, there is an account of ’Ndrja’s first experiences with the opposite sex which, alongside several other scenes, does indeed reveal a coherent picture of the fishermen’s culture and soul. Nevertheless, I was not bored, because D’Arrigo’s way of telling has something very encompassing—it reaches not only the characters’ actions but always touches their innermost being. He combines things very skillfully and creates a clear picture through contrasts.

There were several scenes that somehow shocked and moved me. One describes a German soldier who, during the retreat from Naples, loses contact with his comrades with his tank and is eventually cornered by local boys about thirteen years old. The way the soldier faces death—and especially how the locals do; the light in which this man appears to them; and, very cleverly woven into this image, a young girl with her blind father—all this is quite a powerful combination.

Equally emotional is the story of Federico, a childhood friend of ’Ndrja, whose right hand is mangled in combat. The way he tells his story and how he, too, is embedded in this environment—in the Sicilian landscape that takes possession of everything in the book—and the bitterness that lies in it, again expressed with absolute perfection:

He put his hunk of flesh [meaning the mutilated hand] back into its sheath and pulled the cord with his teeth: again he turned his gaze to the sun, which stood high over the middle of the strait, and looked at it as something terrible and sad, like a cold sun without warmth, a bygone, distant sun, one of the suns that once, in times of peace, shone upon the good boy and the whole horde of his milk-bearded friends; he looked at it in a way that tightens the heart, like a memory, with an apathetic, passionless eye that stood closer to the moon than to the sun. (p. 714)

The third part, ostensibly about the orca—the killer whale—and its significance for the fishermen, slows the book’s pace once again. Here D’Arrigo delves deeply into the mythical image the fishermen have of this sea creature that is almost unknown to them. Again it becomes clear how backward these people were, but also how harmoniously they were embedded in their environment and nature. Their superstition collides with reality; it often seems strange and was sometimes hard for me to relate to. A pronounced anthropomorphization of dolphins, orcas, etc., stands out in this book. On the other hand, I also liked this very much, as it gives rise, for instance, to the legend of the sirens—mermaids who seduce sailors and fishermen, luring them into hidden submarine grottos to emasculate them there. With great detail and a truly evocative mood, a myth is brought back to life. Reading this is pure delight. That said, it must be stated clearly that from the third part onward the book does begin to feel long-winded. On the other hand, it is exciting to observe the sea’s activity with the fishermen, and you get a very accurate insight into the Pellisquadre’s perspective.

In the fourth part the pace drops rapidly again (and that’s saying something). Its central element is a dialogue that stretches over 200 pages and is dissected down to the smallest detail. A trimming here would certainly not have hurt. Of course, this depiction—showing how even the most principled model fisherman is changed by war—is quite worth reading, but the scope of the dialogue is a bit overdone. In this final part, a further explanation for the book’s title also emerges. The orca in this story is a metaphor for the land, for the people—above all the Pellisquadres—and how they changed in wartime, how they were seized by a cynical, embittered, mocking, condescending worldview and succumbed to a certain hopelessness—bereft of any ideal, so it seems to the protagonist. D’Arrigo portrays all these traits in a dialogue and, quite deliberately, precedes this fourth part with an equally exact depiction of the orca. How D’Arrigo can handle language is impressively demonstrated here, as he proceeds from the word Barke (barque), through (word)play to Bare (bier)—for the fishermen sent their dead to sea and buried them on old, decommissioned barques. From Bare and Barke he arrives at Arke, extracted from the coined word Arkelamekk: the Arke as an emblem of the Ark for the Pellisquadres.

That the orca is interwoven with the war, mirrors it, and that much in the novel is reflected in it is made explicit in several places:

Thus, not only the return of the Orcaferon took place there before them, but also the arrival of that English and American fleet in the port of Messina. […] Unless one allowed oneself to be misled into thinking that a fleet of war is also an Orcinuse—that it too brings death. (p. 949)

And so the Orca, the Orcaferon, the Orcadaver, the Orcinuse, the Tödin—all names the author gives this sea monster—thus it is not only a metaphor but also a living portrait of death, which seems to hover perpetually over this book—especially in the last part and most of all in this fourth part, which once again shows what war means for people and a country. And to underscore this transferred meaning of the orca, D’Arrigo does what he masters: he changes the language—and calls his book Horcynus Orca.

Conclusion: Horcynus Orca is a detailed portrait of the Pellisquadre—the Sicilian fishermen—their lives and their culture. It shows how the Second World War changed their lives, but also how their very own war against the dolphins and the adversities of everyday life is bound tightly to the sea. It shows their soul—why they are as they are—and not only depicts it but brings these simple people’s special perspective back to life, making it tangible.

This book—with its wonderful sentences, its unique language, its constant exposure to the influence of the sea, its realistic look at war but also its dreamlike gaze at ancient myths—is a masterpiece. It plays in the premier league; for me it can be named in the same breath as Tolstoy or Dumas, who created similarly outstanding, timeless language and cultural depiction.

At the same time, Horcynus Orca is very extensive and demands a great deal of attention and time from the reader. In some places the story becomes very slow, and D’Arrigo delves very deeply into individual people and trains of thought. Sometimes this is still very entertaining; often the reader is rewarded with a richly detailed feeling; sometimes, however, it feels rather distracting.

An epic that is highly recommended—and one whose reading I can only recommend to anyone who does not shy away from its length and loves the sea.

Tip: Anyone reading this book will encounter many foreign words and neologisms. It sometimes happened to me that I skipped over them the first time—when they are sometimes explained in more detail. Paging back to find something is really difficult given the sheer volume of text. Fortunately, Google offers a full-text search of the book: http://bit.ly/1D9Fal1. There you can search the book (see the search field on the lower left) and also sort results by page. That way you can quickly find the passages where a word first appeared.

Book information: Horcynus Orca • Stefano D’Arrigo • S. Fischer Verlag • 1472 pages • ISBN 9783100153371

Danke, danke, danke für diese ausführliche, detailreiche Rezension! Das Buch steht nun seit Jahresbeginn auf meiner Wunschliste – zum einen da mich Geschichten, in denen das Meer eine tragende Rolle spielt, magisch anziehen, zum anderen aufgrund der Entstehungs- und Übersetzungsgeschichte. Du bist nun der erste im Bloggerumfeld, der das Werk komplett gelesen hat und man merkt deiner Rezension an, wie intensiv du dich mit der Lektüre beschäftigt hast. Mir hast du damit eine noch bessere Vorstellung davon ermöglicht, was mich erwarten wird. Nun möchte ich “Horcynus Orca” erst recht lesen – spätestens beim Vergleich mit Tolstoi und Dumas hätte ich nicht länger widerstehen können.

Vielen Dank auch für den Tipp mit der Google-Suche!

Liebe Kathrin,

vielen Dank für dein Kommentar. Ich kann mir vorstellen, dass es vielen so geht wie dir. Ich hab angesichts des Umfangs auch erst überlegt. Aber es hat sich gelohnt und es freut mich, dass dir mein Beitrag eine vage Vorstellung von diesem Epos geben konnte.

Liebe Grüße

Tobi

Hi Tobi,

von meiner Seite gibt es zweimal Respekt zugerufen. Einmal, dass du dieses Monstrum an Buch bekämpft hast und zum Zweiten für die wunderbare, umfangreiche Rezension, die einen Eindruck vom Buch und den Genüssen aber auch Schwierigkeiten damit vermittelt. Bei Mara von buzzaldrins, die es ja für Leipzig gelesen hat, wurde ich auf das Buch das erste Mal aufmerksa. Nach deiner Besprechung ist das Interesse weiterhin aufrecht da. Ich werde es aber etwas auf die lange Bank schieben und wie einen guten Wein reifen lassen, da mich noch ein Buch ähnlichen Kalibers vom Buchschrank anlächelt (Stichwort Unendlich und Spaß).

Gruß Marc.

Hallo Tobi,

das nenne ich mal eine würdige Rezension. Ohne das Buch und dessen Inhalt wirklich zu kennen weiß ich: Jede Seite ist sicherlich goldwert. Dieses Werk ist zudem sehr Interessant, deine Schilderung darüber lässt mich nicht abgeneigt zurück. Ich bin positiv überrascht, wie deine Bewertung dazu doch tatsächlich ausfällt. Du weißt anscheinend eben, wie man so etwas bewertet.

Allerdings würde mich persönlich tatsächlich der Umfang und die Fremdwort Quote noch lange davon abschrecken. Nicht, weil ich es nicht nicht lesen möchte. Ich möchte mich in dieser Hinsicht herantasten und irgendwann eventuell mal zu diesem großen Buch greifen. Wenn ich Zeit und richtig Lust darauf habe. Das kann spontan kommen, das kann aber auch noch Jahre dauern. Wer weiß?

Ich danke dir für diese aufwändige, ausführliche und lesenwerte Rezension. Das ist echt sagenhaft. :)

Liebe Grüße

Henrik

Hallo Henrik,

vielen Dank für deine Worte und dein Interesse an der Rezension. Ich hoffe ich habe dich von diesem echt klasse Buch nicht abgeschreckt. Ich denke da geht jeder etwas anders heran, an so ein Buch. Ich gehöre zu der Sorte, die sowas in einen Rutsch durchlesen. Was aber schon ein wenig Durchhaltevermögen erfordert, denn man braucht einfach seine Zeit. Manche lesen sowas immer wieder über einen längeren Zeitraum, lesen aber parallel noch andere Bücher. Das halte ich auch für absolut legitim, denn nicht jeder hat Lust einen Monat nichts anderes zu lesen.

Der Text ist natürlich anspruchsvoll, aber ich kann dich nur ermutigen dich an das Buch heranzuwagen. Ich ertappe mich immer wieder dabei, wie ich daran denken muss, an einige Szenen und Dinge die da passiert sind und sich irgendwie in mein Gedächtnis gebrannt haben. Aber auch an die schöne Sprache, die in dieser Form sicherlich einmalig ist.

Herzlichen Dank für deine Worte. Schön, dass die Rezension gefällt!

Liebe Grüße

Tobi